Introduction

The rising cost of long term care insurance (LTCI) has become a vexing issue for Massachusetts and the country as a whole. Our office often hears about the cost of LTCI premiums from constituents, who in some cases are seeing annual increases as high as 20%–30%. In response, Senator Brownsberger asked his team to research why these increases are happening and how Massachusetts regulates these insurance products.

We are sharing our findings through a series of three posts. This first post introduces the underlying long term care financing crisis. The second one examines the market for long term care insurance, including the factors behind rising premiums. The final post overviews how Massachusetts regulates LTCI and what consumer protections are afforded by law.

Professional long term care (LTC) is an essential service that helps seniors with activities of daily life. It is increasingly out of reach for many. The relative price of LTC has been rising for at least the last two decades. Many experts suspect a shortage of LTC providers to be the primary cause. The extent of the increase is causing many seniors to deplete their savings. In Massachusetts, LTC is often more expensive than much of the country. While premium increases are not necessarily a result of rising LTC costs, examining this crisis provides important context.

Paying for Long Term Care

Long term care is different from medical care; its aim is providing people with disabilities or chronic conditions essential assistance with daily life, not curing or managing specific health problems.

Long term care (LTC) involves assistance with certain activities of daily living (ADLs) that have been made challenging by a disability or chronic condition. These may include bathing, continence, dressing, eating, toileting, and transferring (moving to or from a bed, chair or wheelchair). Common examples of LTC include in-home care, nursing home care, respite care, and hospice care.

A growing proportion of Americans are expected to need LTC as life expectancies increase. It is estimated that 70% of Americans aged 65 and older will need some form of LTC before death, and about half will receive some amount of paid care. Most paid LTC episodes are relatively short, with the majority lasting under 2 years. However, low income individuals and people of color have been found more likely to need lengthier stays.

(Our research focused on LTC for disabilities and chronic conditions in seniors. People with certain disabilities or medical needs may receive similar care at any age. Our research focused on the cost and coverage of paid LTC provided by professionals.)

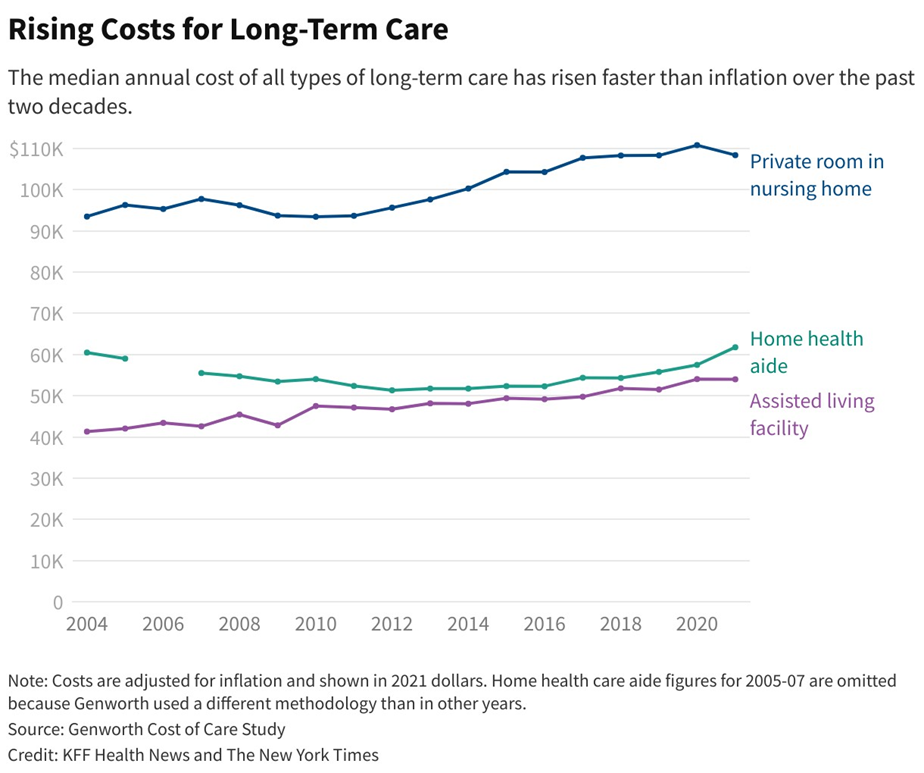

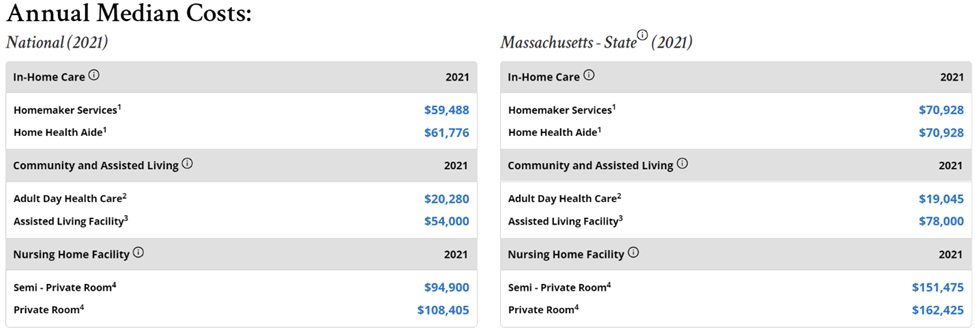

The relative cost of LTC has been rising for at least the past two decades, and that trend is expected to continue. LTC services in Massachusetts are often more expensive than in much of the country.

The cost of LTC services has generally risen faster than inflation for the last twenty years. This trend is driven by a variety of factors that economists are still studying. An in-depth examination is beyond the scope of our research, but it is often believed there have not been enough providers to meet the growing demand for LTC. Following the basic laws of supply and demand, a shortage of providers would push prices upward.

(This post mostly examines national trends. However, Massachusetts is very much in line with the trends described here.)

The Kaiser Family Foundation and the New York Times produced the following figure as part of their recent investigation into the long-term care financing crisis.

Long term care is expected to remain expensive. A 2015 study by the US Department of Health and Human Services estimated that Americans turning 65 that year will spend an average of $72,000 out of pocket. The same study estimates that roughly one-in-six (17%) will spend at least $100,000 on LTC.

Massachusetts has not been immune to these trends. Available data suggest as of 2021, LTC services in Massachusetts were typically more expensive than in much of the country. However, costs do vary within Massachusetts. For example, the 2021 median annual cost of an assisted living facility in Pittsfield was estimated to be $25,008; in Boston, the median annual cost was $81,825. Costs are expected to rise. By 2027, the median annual cost of an assisted living facility in Massachusetts is projected to be $93,136.

Rising LTC costs are becoming a serious financial strain on many families and individuals. Government assistance often becomes necessary to receive paid care.

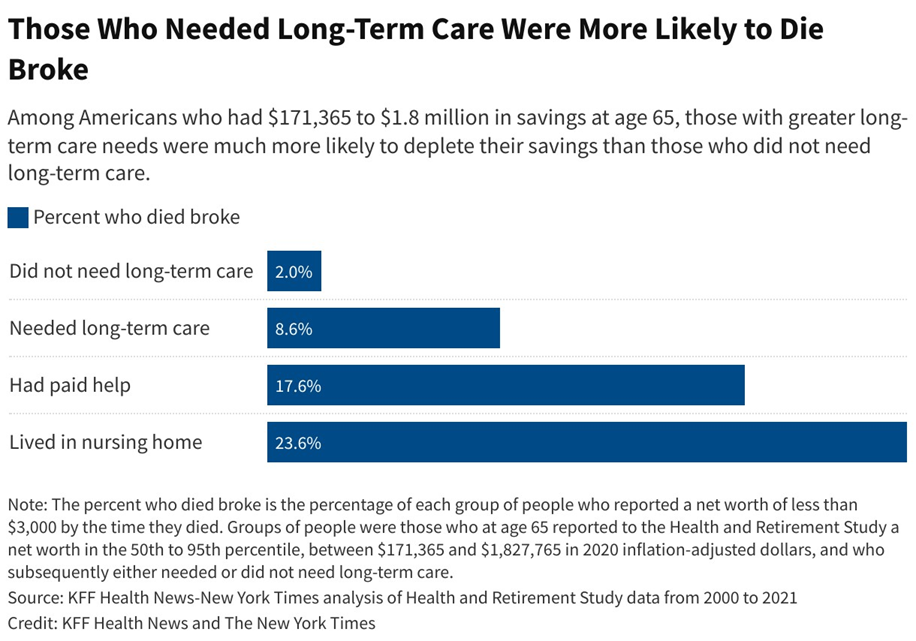

Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation and the New York Times suggests seniors who received paid LTC were more likely to deplete their savings to the point of having a net worth under $3,000 by the time they died. Roughly one in six seniors who used some form of paid care had this outcome. Given that LTC costs are expected to rise, they will likely continue to be a serious financial burden for many older Americans and their families.

Among seniors turning 65 in 2021-2025, only 8% of their total LTC spending is expected to be financed by private insurance nationwide. A larger portion (37%) will be financed out-of-pocket. The majority of LTC spending will be funded publicly (58% total), primarily by Medicaid (43% total). In Massachusetts, Medicaid is administered as MassHealth. Many seniors spend down their assets to qualify for Medicaid to finance their LTC needs. Doing so helps them afford paid care but leaves little for other expenses. And having spent assets down, less is left for beneficiaries after death. Nevertheless, Medicaid plays a critical role in financing LTC for the most vulnerable.

(The vast majority of LTC is performed for free by family and caregivers. As a result, most seniors are able to keep more of their savings. Our research focused on the cost and coverage of paid, professional LTC.)

Conclusion

Middle and low income Americans often have few good options for financing paid LTC.

Neither the public or private sectors can currently finance professional LTC in a way that provides the level of care many people need at a price most people can afford. This has led to LTC being mostly provided informally by loved ones and caregivers at home.

For some seniors, informal at-home care is not an option. Without considerable means, finding care can be stressful and difficult to afford for these individuals and their families. This does not mean it is impossible to find an arrangement that works. It often does mean that difficult choices have to be made about accepting an unideal cost, level of care, or both.

Government at every level is aware of the LTC financing crisis and is working to find solutions. It is a long term problem that requires action on multiple fronts to address.

The LTC financing crisis provides important context for understanding the rising cost of long term care insurance.

While long term care insurance (LTCI) premium increases are not necessarily a result of rising costs, the LTC financing crisis is a crucial part of what makes them so hard to navigate. Consumers are being squeezed on two sides – by rising LTC costs on one, and rising insurance costs on another. What should be a resource to make LTC more affordable sometimes becomes a compounding factor of what makes it so expensive. Consumers may pay expensive premiums for years before they receive benefits, by which point the rising cost of services has eroded their actual value. In effect, some consumers are paying increasingly higher prices for increasingly lower benefits. This does not mean that LTCI is never a good investment. With sufficient means, the right plan can help consumers cover costs while assuring a high quality of care.

This interaction of LTC and LTCI costs reframes the problem of premium increases. With respect to the total costs many seniors are facing, rising premiums are often only part of the equation. The wider LTC financing crisis makes them all the more significant.

Part Two: The Cost of Coverage

Isaac Gibbons is Senator Brownsberger’s Legislative and Policy Analyst.