Introduction

Professional long term care (LTC) is an essential service that helps seniors with activities of daily life. It is increasingly out of reach for many. Our previous post examines the financing crisis affecting access to LTC. The relative price of LTC has been rising for at least the last two decades for a variety of economic reasons. The extent of the increase is causing many older Americans to deplete their savings. The final post overviews how these insurance products are regulated in Massachusetts.

Private insurance can be a helpful tool to defray some of the cost of LTC. However, the cost of long term care insurance (LTCI) has also risen. For plans issued before the early 2000s, carriers made forecasting errors that led them to raise premiums – sometimes dramatically. Newer plans tend to be much more expensive than older plans initially were. Many carriers have stopped offering LTCI products altogether, resulting in less choice and access for consumers. This mix of high cost and low access have made the products unavailable or unaffordable to most Americans. This dynamic is present in Massachusetts, as well.

These developments put consumers in a troubling position. Buying or keeping LTCI can be prohibitively expensive, but so can going without it.

Long Term Care Insurance

Amid rising LTC costs, private long term care insurance (LTCI) can be a valuable financial support. However, it is underutilized and often unaffordable.

Long term care insurance (LTCI) is designed to cover future costs of care associated with a chronic condition or disability that requires long term care. People often buy policies decades before they will need coverage. Generally, the later in life someone buys LTCI, the more it will cost; companies want to maximize the amount of time they collect premiums before paying benefits.

Traditional LTCI products are usually “guaranteed renewable.” This means a policy generally may not be cancelled by the insurer for any reason except failure to pay premiums. However, carriers are allowed to be more selective; medical underwriting is permitted and carriers may deny coverage for pre-existing conditions.

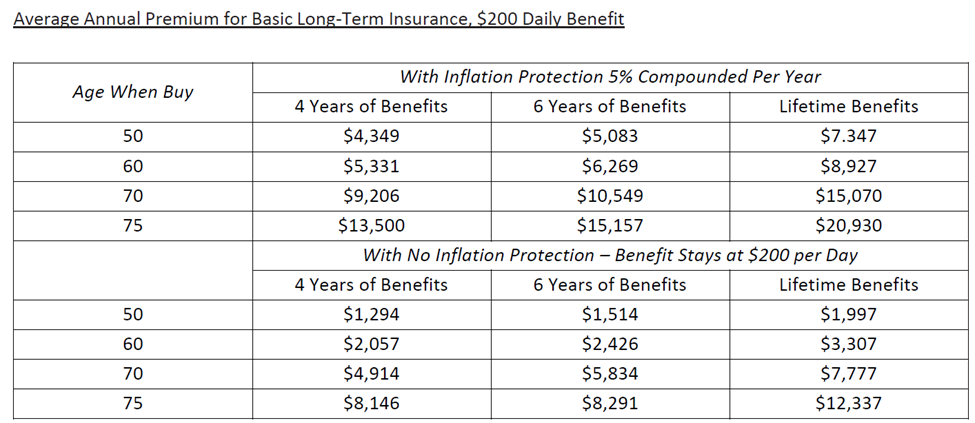

Buyers have a range of benefits to choose from in a given LTCI plan. For traditional products, buyers must choose daily benefits, a benefit duration, and whether to purchase inflation protection (among other options). The dollar amount of the daily benefit is often initially chosen by the customer based on the current cost of LTC services. The benefit duration is the length of time a policyholder may receive benefits. Durations may range from a few years to lifetime benefits. Inflation protection can help offset growth in the price of services. A higher daily benefit, longer duration, and/or more inflation protection come at the cost of higher premiums.

The following figure shows the average annual premium for basic LTCI with a $200 daily benefit.

Long term care insurance pays benefits once policyholders have a demonstrated need for LTC services. Such needs (“benefit triggers”) trigger benefits when a policyholder is unable to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) without help. ADLs usually include bathing, continence, dressing, eating, toileting, and transferring (moving to or from a bed, chair or wheelchair). Specific criteria for benefit triggers vary by plan.

Long term care insurance may help protect an individual’s savings. However, the return on investment for LTCI depends on whether the amount and duration of future benefits will be worth the cost of premiums.

The price of LTCI has risen while carriers have left the market in large numbers.

According to research by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the New York Times, LTCI customers today are often effectively paying higher prices for less coverage. A decade ago, a couple aged 55 could expect to pay on average $3,725 a year for a traditional policy that included $162,000 in total benefits and 3% inflation protection. Today, virtually the same coverage for a couple the same age would cost $5,025, 35% more, even as growth in the cost of LTC has eroded benefits.

Sales of traditional LTCI have fallen in the last decade, despite the growing need for long term care. Carriers went from selling 754,000 new policies in 2002 to only 129,000 in 2014. By 2018, that number dropped to 58,000. Similarly, the number of major carriers offering traditional, stand-alone products nationwide has dropped precipitously from 125 in 2000 to about a dozen as of 2023.

Newer products called “hybrid” or “combination” LTCI plans have become more popular. These typically function as an add-on rider to a life insurance policy that allow policyholders to access their death benefit early (known as an “accelerated death benefit”) to pay for LTC expenses. The market for these products is growing, although they are still expensive.

Some of the most dramatic premium increases have occurred for plans issued before the early 2000s. A series of forecasting errors left carriers unprepared to cover the cost of future claims.

Rates on traditional products were initially set much lower than carriers could actually afford. Carriers eventually needed more income from premiums to cover the cost of paying out benefits and make up for shortfalls. In some cases, the magnitude of the potential losses threatened carriers’ long-term solvency. As costs mounted, carriers pushed for significant premium increases to minimize losses – some over 100%.

In short, the industry underestimated how long policyholders would live and how frequently they would file claims, overestimated how many would drop their coverage before ever receiving benefits, and incorrectly assumed higher investment income. As a result, carriers were on the hook for more claims than they had anticipated, paying these claims out for longer than planned, and left with fewer reserves to cover future costs.

An evaluation of the assumptions carriers made when they first sold LTCI products is beyond the scope of our research. However, we should note these errors were not isolated incidents. Actuaries and researchers for dozens of insurance firms all made similar errors. Regulators across the country ultimately approved the products, having made their decision given the data available at the time.

See Appendix A for a more detailed explanation of the factors behind these premium increases.

Conclusion

Prices of LTCI have risen over the last decade, while the profitability of these products has generally fallen. Even as projected demand for LTC services grew, the market for LTCI constricted.

Carriers have increasingly left the market for traditional LTCI products due to poor returns. Research from the Department of Health and Human Services indicates carriers started leaving the market when they realized the amount of capital needed to finance claims was prohibitively high. Because policyholders were using benefits more frequently and for longer than carriers had expected, carriers needed considerably more money on hand. They had to both pay claims moving forward and insulate themselves from losses that could threaten their solvency.

Carriers raised premiums, only to learn the market for such an expensive product was considerably smaller – and often less profitable. The vast majority cut their losses and stopped offering the products altogether. The remaining few raised premiums to a level fewer customers could afford to pay. Many carriers updated their underwriting practices to minimize the risk of covering policyholders that would develop more costly LTC needs. Doing so may have made the customer base even smaller.

The result of these developments has been a constricted market for traditional LTCI, with fewer carriers offering the products and fewer consumers buying them.

The current state of the LTCI market presents a complicated set of dynamics for government to navigate.

Regulators and policymakers are challenged with balancing the need to protect consumers from unreasonable rate increases with the need to foster a functioning marketplace for LTCI. It is likely not in the public interest for more carriers to exit the market. At the same time, many consumers are struggling to finance LTC; there is a public interest in making LTCI as affordable as possible.

In our third and final post we examine how Massachusetts state government currently regulates LTCI products, and how these sometimes competing public interests are managed.

Appendix A

Lack of experience data:

To create accurate pricing models, carriers typically use years of data of how insurance claims occur in real life – so called “experience data.” Experience data serves as a crucial reference point for how often policyholders tend to file claims, keep their coverage, or drop it.

When LTCI policies first became popular in the 1980s and 1990s, there was no experience data to reference; the products were too new. And because pricing LTCI involved estimating claims decades into the future, there was significant potential for error.

Carriers generally used proxy sources from health and life insurance policies and long term disability data, as well as nursing home studies containing morbidity rates. This approach assumed that together, these various sources would help give an accurate picture of how people would use LTC services in the future. Unfortunately, their confidence in this data was misplaced. Trends in demographics, healthcare, eldercare, and the wider economy moved in directions the industry had not anticipated.

Morbidity rates:

To set premiums appropriately, carriers must accurately estimate the rate at which policyholders will claim benefits, and for how long. If more policyholders are expected to claim benefits, premiums may rise to cover the cost of paying more claims. The rate policyholders use benefits is called the morbidity rate. LTCI carriers seriously underestimated morbidity rates when they initially offered their products. As a result, initial premiums were offered lower than they should have been.

The calculations for morbidity rates are based on several different components, including incident rates (the frequency policyholders claim benefits), claim continuance patterns (the frequency and/or time periods policyholders claim benefits) and disability patterns and recovery rates that may impact a person’s need for and use of LTC. Due to longer life expectancies, changes in medical practice (e.g., diagnostic criteria for cognitive disabilities), changes in the provision of LTC services (e.g., the number of services required for a given disability in a LTC setting), and a host of other factors, actual morbidity rates were considerably higher than carriers expected. As a result, carriers had to pay out more claims than anticipated, and often for longer.

Mortality rates:

As was discussed in the previous section, carriers try to estimate the likelihood that someone will receive benefits and for how long. For LTCI products, projections of how long policyholders will live are a crucial part of that estimation. Whether a policyholder lives well into old age then receives benefits for one year or three has a major impact on whether and how long an insurer can expect to pay benefits. If mortality rates are low, premiums may rise to finance the higher number of claims to be paid. LTCI carriers overestimated mortality rates, leading to lower initial premiums than they should have offered.

Carriers again used proxy sources given the lack of experience data. Actual mortality rates turned out to be much lower than the available data may have indicated. More policyholders reached older ages, which carries a higher risk of becoming disabled. And once policyholders became eligible for benefits, they were living longer – thereby using services longer. Again, more claims were filed than carriers had anticipated, and paid out for longer than planned.

Lapse rates:

Carriers must also consider how many people will actually stay on their plan until they are eligible for benefits, and how many will drop it before that point. If more people are expected to stay on their plan, the chance the carrier will have to pay benefits increases. If the carrier is more likely to pay benefits, premiums rise to cover the cost. The rate at which policyholders drop their coverage is called the lapse rate. Carriers overestimated lapse rates, which led them to offer lower premiums than they should have.

Carriers had tried to use data from other kinds of insurance products to estimate how many policyholders would drop their coverage. No data on LTCI lapse rates existed at the time because the product was too new. Unfortunately, their projections were inaccurate. Many more policyholders kept their coverage than anticipated. As a result, carriers were on the hook to pay out more benefits than planned.

Investment income:

Insurance carriers invest funds from premiums in financial markets, often in low-risk bonds. They factor in income from these assets when they are calculating how much they will have on reserve to cover future claims. If investment income falls, premiums may rise to offset the loss and bolster reserves.

Interest rates had a major impact on the performance of carriers’ investments. Carriers had expected interest rates to rise from where they were during the 1980s and 1990s and invested accordingly. However, the interest rate environment of the next few decades was unforgiving. The federal funds rate remained at historically low levels until recent increases in response to post pandemic inflation. Carriers had earned less investment income than they had anticipated. With less in reserve than planned – and a larger number of claims to be paid than originally assumed – many LTCI carriers were in a difficult financial position. Many applied for rate increases to offset their losses.

Part 3: Public Policy Overview

Isaac Gibbons is Senator Brownsberger’s Legislative and Policy Analyst.