Recently, many have celebrated Maine’s achievement of 100,000 heat pumps installed. It’s really a good-news/bad-news story.

Broadly, there are three kinds of heat pump installations:

- Simple comfort — a ductless mini-split unit blows hot or cold air as needed into a single room. The unit may or may not indirectly serve other rooms. Simple comfort units may be installed in more than one room, but without any control device that would coordinate the units with the main heating system.

- Partial conversions — one or more heat pumps are installed with the intention of systematically displacing fossil fuels although the fossil heating system continues to be used in colder weather. The heat pumps are coupled with the fossil heating system through an integrated control — a single thermostat that controls both heating sources and optimizes their hybrid use.

- Whole home conversions — one or more heat pumps are installed with the intention of serving all of the heating needs of the home. The fossil system is decommissioned or kept only as backup. Weatherization is usually advised as prerequisite for whole home conversions.

Maine’s 100,000 heat pumps fall mostly in what we are calling the “simple comfort” category. In 2019, Maine’s legislature passed a law requiring the deployment of 100,000 heat pumps by 2025. To achieve that goal, Efficiency Maine designed a program that was as simple as possible — no prerequisites like weatherization, the use of integrated controls, or decommissioning of the fossil system.

As a result, entrepreneurs were able to get rebates for selling heat pumps as air conditioners with no binding requirement that they reduce fossil fuel consumption. In written testimony in August 2021, analysts at Efficiency Maine attributed their rapid heat pump progress in part to the fact that “the summer of 2020 and the beginning of FY2021 was the third warmest on record.” Conversely, in September 2023, Efficiency Maine’s executive director reported to his board that installers were reporting a slowdown in part due to a “mild summer.”

By contrast, the Massachusetts legislature has never set specific heat pump installation goals. Massachusetts has only set green-house gas reduction goals. Mass Save in its current three year plan is not offering rebates for simple comfort heat pumps. It is only supporting the heavier-duty partial and whole home conversions that are better calculated to reduce emissions. It is understandable that Massachusetts volume is lower. However, each Massachusetts heat pump installed does much more to reduce green-house gas emissions.

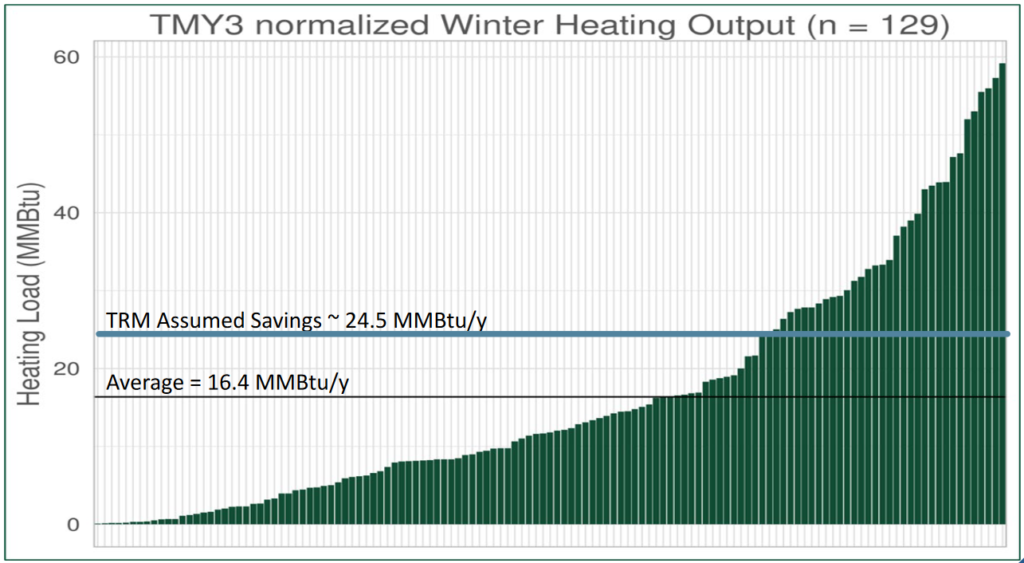

A recent evaluation report for Efficiency Maine indicates that Maine’s heat pumps are not being used for heating to the extent expected – only 39% as much as expected for commercial and industrial customers and 67% as much as expected for residential. The average heat generated by heat pumps in the studied sample of 129 Maine homes was 16.4MMBtu/yr (million British thermal units of heat per year) as opposed to a target level of 24.5MMBtu/yr. By contrast, Mass Save is targeting 50MMBtu/yr for partial conversions and 84MMBtu/yr for whole home conversions. See, MeasYR1 Tab of Eversource Electric 4-1-2022 BCR.

Annual heat output measured from 129 Efficiency Maine heat pumps

An evaluation is underway to determine how closely Mass Save is approaching its per-heat-pump fuel displacement goals. But if the program is working as intended, Mass Save may be saving over 4x the per home result in Maine: According to quarterly reports, KPI #3, Mass Save is funding considerably more whole home than partial conversions, so a blended average of 70MMBtu/yr is likely.

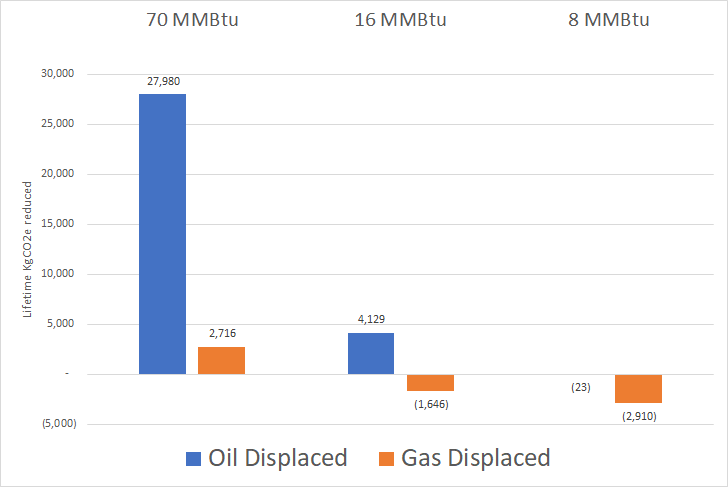

The per-home Mass Save results in oil-heated homes look 7x better than Maine’s when one considers the impact of refrigerant leaks — compare the first two blue columns in the chart below. Heat pumps are filled with refrigerants that are potent greenhouse gases targeted for phase-down by international treaty and by the EPA. A substantial leak by one modest heat pump can equate to one year of driving in terms of climate impact. The leakage data are poor and experts differ on the likely average lifetime amount of refrigerant leakage during operation, maintenance, and decommissioning. However, an average 100% lifetime leakage is a reasonable guess. Some heat pumps leak all of their refrigerant more than once and sloppy decommissioning is all too likely.

If a heat pump is heavily used for heating — as intended in Massachusetts installs — the operating climate benefits will usually offset the harm done by typical leaks. However, the chart above shows that, in Maine’s simple comfort installs, roughly 1/3 of the heat pumps are being used to displace less than 8 MMBtu/yr. As the chart below shows, these heat pumps are a net negative from a climate perspective — they produce more greenhouse gas from leaks than they save through operations, whether they displacing oil or gas.

Heat Pump Lifetime CO2e Net Savings Under Alternative Fuel Displacement Scenarios (Fuel Type x MMBtu saved)

Because of the low fuel displacement rates in its simple comfort program, as of September 18, Efficiency Maine has pivoted and is now providing incentives only for whole home heat pump conversions. The simple comfort installs are still supported for low-income homes. Certainly, as summers warm, everyone will need air conditioning, especially the elderly and disabled.

Massachusetts never had the option of conducting a program like Maine’s, focused on simple comfort installs. There is an important difference between Massachusetts and Maine: Most homes in Maine heat with oil or propane, while in Massachusetts a solid majority heat with natural gas. Natural gas creates lower greenhouse gas emissions than oil (even including methane leaks). As a result, for a Maine-like program of simple comfort installations saving 16 MMBtu/yr in gas-heated homes, the net environmental impacts of the whole program would be negative.

Massachusetts’ overall savings opportunities are lower since natural gas dominates, but Massachusetts’ focus on heavier-duty conversions has optimized bottom line impacts. As a counterfactual to compare the relative effectiveness of Maine and Massachusetts programs, imagine (contrary to fact) that most of Massachusetts 2022 installs had occurred in oil-heated homes, then the overall per capita green house savings would exceed Maine’s program. These computations are detailed in the attached pro-forma spreadsheet, but flow from the insight in the chart above — for heat pumps to be environmentally beneficial, they have to be operated enough to offset the harms they do by leaking..

While Maine’s broad-based, high-quantity, simple comfort program is not a good model for Massachusetts, there is one lesson Maine may offer: Simplicity matters. Maine experimented with the partial conversions involving integrated controls which are an important part of Massachusetts current program. After Maine’s integrated controls pilot program, Maine chose not to continue with them. In a recent talk in Boston, Efficiency Maine’s executive director expressed concern about the complexity of integrated controls in partial conversions. It remains to be seen how the next Mass Save evaluation will come out — to what extent are assumed fuel displacement results being achieved with integrated controls in partial conversions? It may be that the Maine and Massachusetts programs will ultimately converge to a similar exclusive focus on whole home conversions.

Note that the entire discussion above has focused purely on the greenhouse gas impact of Massachusetts and Maine programs. Additional analysis focused on overall social cost-effectiveness and/or on financial impact for consumers would raise additional concerns about applying the Maine model in Massachusetts where the majority of homes use natural gas.

Can Maine learn from Massachusetts?

When all program activities and external factors are combined in bottom line measures, Massachusetts seems to be making more progress than Maine. Mass Save and Efficiency Maine both got started around 2010 based on similar legislation. From 2010 through 2021, Massachusetts cut residential energy use 4%. That is not stunning progress, but through the same years Maine has slipped backwards, increasing residential energy use 6%. Similarly, as to residential emissions, Massachusetts is down 8%, but Maine is flat. On a per capita basis, Massachusetts’ residential emissions are down 13% while Maine’s emissions are down only 4%. See attached spreadsheet. Massachusetts has typically come in at or near the top in national utility efficiency program rankings.

Maine might learn from Massachusetts on weatherization. Efficiency Maine has incentivized only about 4000 envelope measures per year for the last couple of years, but Mass Save’s annual volume of envelope measures has been over 60,000. Massachusetts’ weatherization rate is therefore over 3x as great as Maine’s allowing for the fact that Massachusetts has 4.6x as many housing units as Maine.

I wish you put your considerable energies into a true environmental concerns, of which there are many. CO2 makes up .04% of Earth’s atmosphere. Of that % around .03% is attributable to human activity. Most of the CO2 comes from oceans, plants, volcanos, etc. Photosynthesis is reduced to dangerously low levels once hits .02%. Many, even on the Left, are coming around to the real agenda of controlling people,etc. You’re a bit behind the curve.

Very interesting. How can I find out more about your perspective??

If we all convert everything in our homes to electric, and the power goes out, then we’ll have no other options.

That’s another reason why hybrid cars are the only thing that should even be considered being mandated right now by the state legislature.

You’re going to have to walk your support of that all electric car mandate back, aren’t you?

This obsessive focus by someone as high in Senate leadership as yourself to push your constituents to go all electric at this time seems more like an ideology than a public service benefit.

Thanks so much for digging deep beyond the headlines to present a great analysis of what the Maine program is, and how it compares with MA

Will, thanks for this. Refrigerant leaks deserve a lot more study. I don’t understand how they are included in your bar graph. More importantly, saying “an average 100% lifetime leakage is a reasonable guess. Some heat pumps leak all of their refrigerant more than once and sloppy decommissioning is all too likely.” sounds like a gigantic adjustment to the cost-benefit tradeoff, both in Maine and Massachusetts because the equipment failure rate should be the same in both states. I see the link includes more discussion about leaks but the takeaways from that discussion are not easy to follow.

Thank you. The data are poor, but I’ve clarified the discussion in the link.

CFCs in insulation material. How do we keep totalitarian bad actors from cheating on a heat pump and putative insulation boom? We can’t.

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-48353341

To make this work America has to project strength.

Mass Save has a fundamental problem. It is based on the party having a relationship with the gas company. It is not landlord friendly and quite frankly landlords don’t have a lot of incentives to weatherize units and upgrade to heat pumps. Considering the high percentage of homes/units that are rentals in the Boston area this is a huge problem. Keep in mind incentivizing landlords to make the conversion will benefit tenants the most as they will get reduced utility bills.

The relationship with the gas company is not necessarily problematic. The gas company is a regulated utility that follows the incentives we create for it and we do create strong incentives to have successful conservation programs. But I definitely agree that rental housing is challenging — actually Mass Save and the Energy Efficiency Advisory Council devote a lot of attention to trying to do better in that space.

Thanks so much for this useful analysis. It is rare and important to follow up with how things are working rather than relying on initial projections.

Thank you Will for providing this data and analysis. Echoing Colleen, it is important to see how things are working over time after the good faith implementation of environmental programs, and to learn from the analysis. I appreciate the effort to bring in less obvious factors such as refrigerant leakage and decommissioning as a part of the overall evaluation.

Regarding heat pump leakage (and it isn’t clear how important that is overall), I guess refrigerants have to have a gaseous state, but aren’t there any that don’t create greenhouse gasses? If there are, why not mandate them? Regardless, why isn’t their disposal regulated?

Good questions. See more discussion here and here.

Short answer, yes, there are some that are not GHGs, but they are not ideal for use in heat pumps.

We don’t have integrative controls at our house. But when the temperature drops below 25 degrees, the heat pumps are manually turned off and the gas furnace is turned on. This is mostly for financial reasons. But it’s also because we’re one heat pump short of having a whole house heat pump solution. There really aren’t that many days when the gas furnace is running. And the quality of the heat from ASHPs is far superior to the old steam radiators, so we are motivated to complete the conversion in the future.

Please provide more incentives for folks to convert. Also please invest in educating the installers. Some installers think that leaks are normal and will recharge systems without fixing the leaks. And they’ll oversize systems.

& thanks so much for your work on this!

Thanks, this is useful. From an actual user!

I have concern about over reliance on utility energy. Once they gain full control, they will charge what they want to. Delivered fuel (oil, propane, etc) is direct competition that keeps prices in check to real world levels. Even at the utility level to a lessor extent Nat-gas is an alternative to electricity. I am also concerned about how we are going to pay for the expansion of the grid. I have noticed the rise in the customer charge which is a fixed amount monthly. I have solar installed and my system is slightly larger than what I consume so I only buy back power in the winter, but I am keeping a close eye on this issue, possibly installing another panel to make up for the customer charge as it increases moving forward. Also I de-electrified my laundry issues. Ditched the electric drier and now line dry in the basement. I am doing the math with Nat-gas replace with propane. (demand heater backup for solar hot-water, Kitchen range) I have a gas fired a comfort heater in the main room considering to replace with pellet heater. In the ideal world I would go off-grid as far as energy is concerned. De utility-ify.