As we consider heat pumps we need to be clear about which framework we are thinking from. This post identifies three alternative frameworks, identifies the quantitative questions relevant to each framework, and discusses the state of our understanding of those questions in each framework.

Possible frameworks include:

- Pure environmental — are we going to hit the climate goals that we have defined for the building sector through our legislative and regulatory process?

- Public benefit-cost — are our heat-pump programs cost-effective given some reasonable estimation of a social cost of carbon?

- How will a heat-pump installation work out for a consumer . . . what should consumers be thinking about in their heat-pump choices?

In every framework, the analysis of heat pumps is sensitive to multiple variables, but not all variables are relevant in every framework. The chart below arrays potential decision variables against alternative frameworks and highlights the extent to which the variable appears, in the real world, to be diverging from assumptions or expectations. Each framework is further discussed below.

Extent of divergence between reality and assumptions/expectations in alternative frameworks

| Building Sector Emission Goals | Public Benefit/Cost | Consumer Benefit/Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Installation costs | n/a | Critical | Critical |

| Installation volume | Critical | n/a | n/a |

| Heat pump efficiency | OK | OK | Watch |

| Portfolio efficiency | OK | OK | n/a |

| Emissions from generation | n/a | OK | n/a |

| Customer behavior | Watch | Watch | Watch |

| Refrigerant leaks | n/a | Watch | Watch |

| Natural gas leaks | n/a | OK | n/a |

| Social cost of carbon | n/a | Watch | n/a |

| Energy prices | n/a | OK | Watch |

| Second order variables | n/a | OK | n/a |

Building sector emission goals

In our emissions accounting framework, emissions from the building sector derive almost entirely from burning of fossil fuels on site for heating, hot water, cooking, and clothes drying. People focused on achieving our building sector emission goals need not consider emissions from electricity generation (which are attributed to the electricity sector). Nor need they give much attention to refrigerant leaks or natural gas leaks (which are attributed to the “non-energy” sector).

From the building-sector-goal perspective, the critical divergence between expectations and reality is simply the pace of change, the volume of installations — we are not installing heat pumps fast enough to achieve our stated goals, although we may achieve widespread use of heat pumps eventually. One additional variable to watch from the building-sector-goal perspective is customer behavior. Many installations of heat pumps are “partial” — the fossil heat remains in place. In these installations, we don’t know to what extent consumers will use the heat pumps for heating.

Public Benefit/Cost

When considering the choice to fund a program of heat pump incentives one wants to broadly assess the ratio of benefits to costs for the program. The volume of installations is irrelevant — relevant to the magnitude of the benefits and the costs, but not to the ratio of benefits to costs.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Public Utilities is charged with reviewing Mass Save programs for cost-effectiveness. Every three years, Mass Save submits its proposed three year plan to the DPU. Stake-holders, including the Attorney General and environmental advocacy groups, litigate the plan’s cost-effectiveness before the DPU. The DPU’s early 2022 approval of the current plan offers a good understanding of the legal framework and issues in controversy as to the cost-effectiveness of the plan. The DPU’s “file room” for the relevant docket numbers (21-120 through 21-129) is a rich source of quantitative information — all of the dimensions of the plan’s cost-effectiveness were heavily vetted through DPU interrogatories to the plan administrators and submissions by all the parties.

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at the benefit-cost models submitted to the DPU and perceive them to be rigorously developed. Most importantly, they use reasonable assumptions as to heat pump efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions from electrical generation. Note that as to GHG emissions from electrical generation, while they use economically correct marginal cost computations in their benefit-cost computations, they also do an emissions computation for EoEEA GHG accounting purposes, a computation which bears no direct relationship to economic reality.

Their long term estimates of energy prices are as good as one can hope, although there is irreducible uncertainty as to both markets and policies. As to second-order effects, like demand reduction induced price effects, their “avoided energy cost study” is the only available source but it is a well-executed study.

They have given careful attention to the question of consumer behavior — how much heat pumps will be used in partial conversions. The question remains open, but the plan administrators have another study ongoing and we will have more data in another year or so as to how the current policy of requiring integrated controls is influencing consumer behavior.

I do feel that the benefit-cost analysis for the current plan should have given more attention to the problem of refrigerant leaks, but for the next cycle, pending federal regulatory actions will dramatically reduce the impact of refrigerant leaks by forcing the use of less harmful refrigerants. The significance of refrigerant leaks as an issue ties closely to the issue of heat pump usage levels in partial conversions — leaks loom larger as an issue if there is a lot of refrigerant sitting in under-used heat pumps that are not generating adequate benefits to offset the costs of their likely leaks.

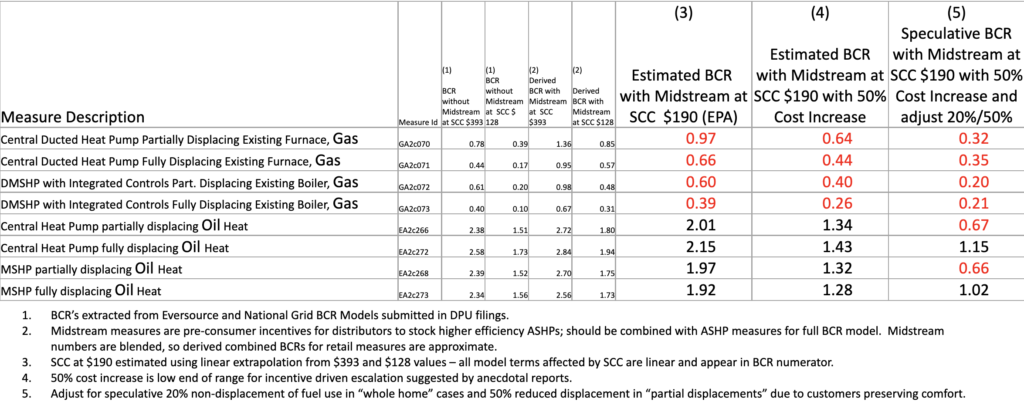

The most heavily litigated issue about the benefit-cost computation was the social cost of carbon, which was originally computed at $393 per ton, but finally computed at $128 per ton. With EPA’s new proposal at $190 per ton, it is likely that the next round of planning will use a higher value. Consideration of the impact natural gas leaks would mathematically equate (in the benefit-computation) to a further increase in the cost of carbon.

The estimating variable that has diverged from assumptions and has the strongest direct impact on benefit-cost computations is the installation costs for heat pumps — our incentives have heated the market to the point that costs are up 50 to 100% above levels assumed in the original benefit-cost analysis. High costs drive down the benefit-cost ratio and even if we increase estimates of the social cost of carbon, many electrification measures will not show as cost-effective when evaluated using their current costs.

Benefit-cost ratios below one for common heat pump installations

In the context of the DPU litigation about cost-effectiveness, one question is how particular “measures”, for example, “central heat pump partially displacing oil heat” are grouped within sectors or programs. See DPU order approving plan at page 111. Most gas displacement measures did not show as cost-effective in the original plan submissions, but the DPU finessed this issue by allowing them to be grouped with other measures. At the time, the volume of gas conversions was expected to be low. As it turns out, there has been a higher than expected volume of gas conversions and in the next planning round the issue of their cost-effectiveness will need to be carefully discussed.

With additional data from currently ongoing studies it may be possible to consider cost-effectiveness in light of overall portfolio efficiency. At this point, it is unknown whether a portfolio perspective would have material effect on measure benefit-cost ratios.

Consumer Benefit/Cost

See also this decision guide for heat pump buyers.

From a consumer benefit-cost perspective, rising prices have diminished the value of incentives and the upfront costs of installation are prohibitive for many and daunting for most. Heat pump operating efficiency is often well below rated values. Even if an installation works out well and proves highly efficient, operating cost savings are highly uncertain — at best modest for oil and often negative for gas. Consumers should never assume that heat pump operating savings will go far to defray their capital investments in a heat pump conversion, especially if they have a moderate income and cannot absorb financial surprises. Consumers doing partial conversions will need to experiment with heat pump operation in winter and consider how to optimize comfort and operating costs.

Refrigerant leaks are not necessarily a big deal to fix — HVAC technicians are all too familiar with the process — but consumers should be clear with their installers about what their warranty is. For people who care about the environment, leaks can be heartbreaking — they can undo several years worth of heat pump environmental benefits. There is a strong argument for waiting until the next generation of heat pumps comes out in 2024 and 2025 — they will use less harmful refrigerants and will likely detect their own leaks. Additionally, the new refrigerants will be more efficient and so more beneficial to the environment — from a lifetime GHG perspective, their increased efficiency will offset the GHG costs of delay. Another reason to consider waiting is that consumers investing in the current generation of heat pumps may be economically forced to retire them early if they leak — replacing the current refrigerants will not be hard over the next few years, but eventually they may become scarcer and more expensive.