Rental vouchers help eligible low-income people pay rent. There are two kinds of vouchers: Mobile and project-based. Mobile vouchers can be used to help pay rent in any apartment. Project-based vouchers (PBVs) can be used only in a particular affordable housing project. A long-term PBV contract can provide a project with a reliable income stream that can help to fund the development and/or operation of the project. Most commonly, PBVs are used in a targeted way to deepen affordability of units so as to support Extremely Low Income (“ELI”) people. This post collects information on the use of PBVs to support housing production in Massachusetts.

- The need for operating subsidies for ELI units

- Subsidy layering

- Recent use of project based vouchers in MA

- Project based vouchers in federal spending context

- Technical notes on PBV definitions

- Additional resources

The need for operating subsidies for ELI units

People with extremely low income (“ELI”) often cannot afford to pay rent sufficient to cover housing unit operating costs. In fact, their total income is often below housing unit operating costs. As one comparison point, standards and budgets for Massachusetts public housing units suggest operating costs (including utilities, maintenance, trash pickup, administration, etc.) in the ballpark of $10,000 per year, depending on unit-size mix. Some small units occupied by able seniors may run below $10,000 in annual operating costs, but family units carry higher costs and some units also carry costs for tenant services. See attached spreadsheet. Private housing projects often have to carry additional per-unit costs for property taxes. Additionally, all projects need cash flow above operating costs to fund reserves for major maintenance and system replacements.

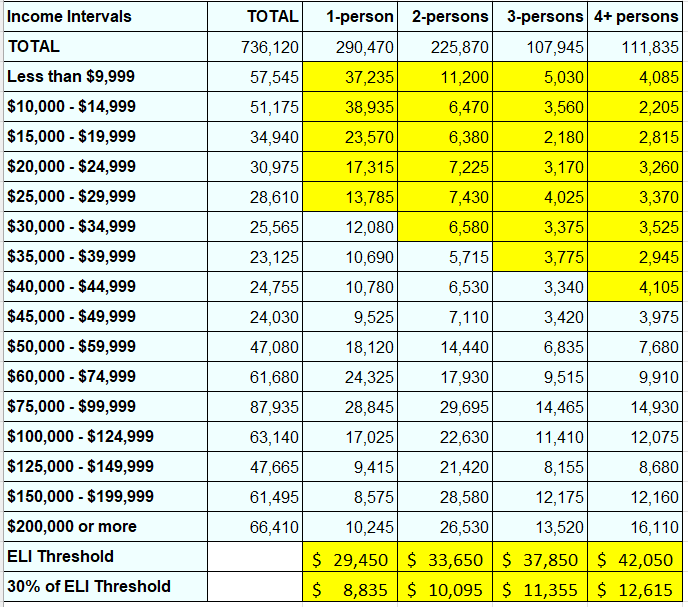

Thirty percent is a standard rule of thumb (and a common regulatory limit) for housing costs as a percentage of income. For the lowest income households, a lower percentage would be appropriate since 30% leaves them with relatively less to pay for other necessities, but we will use the standard rule in discussion below. The bottom two rows in the table below show that 30% of the ELI threshold is approximately equal to $10,000 per unit — below for smaller households, above for larger households. So, ELI households at the top of the ELI range can barely cover operating costs of public housing, much less property taxes and capital reserve costs in private affordable units. The other highlighted cells in the table show that most ELI households have total incomes far below the ELI threshold; these households cannot materially contribute to the operating costs of their unit.

Greater Boston renter households in 2022, cross-tabulated by income range vs. size

(income ranges including ELI households highlighted in yellow) (N=736,120)

State supported public housing units receive an operating subsidy from the state budget intended to cover the gap between rents received and operating costs. For privately operated affordable units targeting ELI populations, the gap between rents received and the operating costs of the unit (and property taxes and capital reserve) has to be made up from some place. One possibility is cross-subsidy from other units. This is only possible when the project mix includes market rate units or units that are rent-restricted to be affordable at some relatively high level. For projects with a deeper affordability mix, project based vouchers help make up the gap by paying near market rents for some or all of the units occupied by ELI people.

Subsidy layering

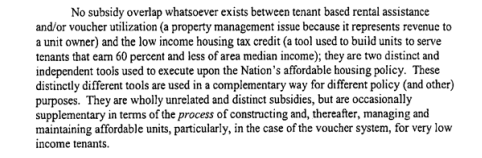

Although the issue is now settled, there has been some controversy in the past about the appropriateness of using rental-assistance vouchers which pay fair market rent — either mobile or project based — in combination with tax-credit-based construction financing which requires a commitment to offer the unit at a deeply restricted affordable rent. Briefly around 2005, PBV rents were capped for tax credit units, but this cap was subsequently lifted in 2007. A 2006 HUD internal audit and the comments on it suggest the debate that was going on within the Bush Administration’s HUD during this period. The text below is a comment from a HUD administrator defending the practice.

Ultimately, the view prevailed that, as already explained, even if construction is fully subsidized, deeply affordable units need operating subsidy. An additional critical point in the debate about layering was that the tax code explicitly contemplates the combination of tax credits with rent subsidies. To be eligible for low income housing tax credits as construction subsidy, developers building affordable housing make a two layer commitment: (a) to charge restricted rent for some or all of their units; (b) to rent those units to people with limited income. This two layer commitment applies to both state and federal low income housing tax credit. However, for the purposes of the rent-restriction, “gross rent” excludes payments made from rental assistance programs like Section 8; in other words, rental assistance that raises total rent received above the restricted rent level does not violate the terms of the tax credit award.

. . . a residential unit is rent-restricted if the gross rent with respect to such unit does not exceed 30 percent of the imputed income limitation applicable to such unit. . . . gross rent does not include any payment under section 8 of the United States Housing Act of 1937 or any comparable rental assistance program (with respect to such unit or occupants thereof),

26 U.S.C. 42 (g)(2)

Conversely, section 8 project based voucher regulations, 24 CFR 983.301(d), explicitly allow tax credit supported units to receive project based-voucher rent payments at the same rents as other PBV units. The only exception is in the counter-intuitive case that the restricted tax credit rent works out to be higher than fair market rent, in this case the voucher payment may (under certain circumstances) be based on the higher restricted tax credit rent.

In general, federal PBV rents are computed as follows:

the rent to owner must not exceed the lowest of:

(1) An amount determined by the PHA in accordance with the Administrative Plan not to exceed 110 percent of the applicable fair market rent (or the amount of any applicable exception payment standard) for the unit bedroom size minus any utility allowance;

(2) The reasonable rent; or

(3) The rent requested by the owner.

24 CFR 983.301(b)

Although the combination of rental assistance and tax credit subsidies is both economically rational and now unambiguously lawful, combination remains subject to the IRS proviso that tax credits may be awarded only to the extent necessary to make a project feasible; combination is also subject to HUD review of subsidy layering which speaks to same basic question — how much subsidy is necessary to make the project feasible?

Recent use of project based vouchers in MA

PBVs are primarily used as tool for developing and operating affordable units that serve extremely low income people (“ELI” those with incomes below 30% of the area median income), especially people with disabilities. The federal Section 8 program requires that 75% or more of PBVs be awarded to ELI people. MRVP and ARVP, while not statutorily required to devote a particular share of their vouchers to ELI households, do in practice serve primarily ELI.

Massachusetts plan for allocation of tax credit funding requires all projects to include ELI units; the minimum share ranges from 10% to 15% depending on project type.

Many tax credit sponsors are able to provide more than 13% ELI units in their projects but typically can do so only if they are able to secure sufficient federal or state project-based assistance. Without rental assistance, most ELI tenants simply cannot pay even an affordable rent. DHCD encourages tax credit sponsors to seek alternative sources of federal or state project-based assistance to support additional ELI units, including rental assistance available through local housing authorities as well as [federal project-based assistance for people with disabilities].

Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (“HLC”) Qualified Allocation Plan (“QAP”), page 36 (emphasis added).

The HLC’s most recent general rental funding notice of funding availability offered up to 475 PBVs through three distinct programs — 250 through federal Section 8, 200 through MRVP, 25 through AHVP). Note that the offered volume of Section 8 PBVs is roughly consistent with the actual average volume over the past five years (295 new PBV units per year, see attached spreadsheet). Common elements in the PBV offerings across all three programs were:

- To be eligible for these vouchers, projects had to be approved for at least one other subsidy source.

- Eligible projects are not restricted by type — preservation vs new construction.

- The vouchers are generally to be used for eligible households with incomes at or below 30% of the area median income [“extremely low income“].

- The initial term of commitment of the vouchers to the project is up to 20 years for Section 8 PBVs and 15 years for PBVs from MRVP and AHVP. The commitments may be renewed.

- The preferred unit size is 2 or more bedrooms except for the much smaller AHVP program which is targeted to one bedroom units for people with disabilities.

Using figures from the tables further below we can derive a ball park estimate of the value of these vouchers, which shows that they are a very significant component of the subsidy to be awarded in the funding round.

Ballpark estimate of value of PBV awards possible in 2024 winter notice of funding availability

| (1) | 2024 two bedroom monthly fair market rent in Boston area+ | $2,827 |

| (2) | Annualized rent — (1) multiplied by 12. | $33,924 |

| (3) | Ballpark 2024 median income of ELI 2 person households from HUD 2022 crosstab above | $20,000 |

| (4) | 30% rental share of household income — 30% of (3) | $6,667 |

| (5) | Annual PBV payment amount — (2) less (4) | $27,257 |

| (6) | Number of PBVs (combining all programs in crude estimate) | 475 |

| (7) | Annual combined value of PBVs — (5) multiplied by (6), rounded to nearest million | $13 million |

| (8) | Contract term (average of Section 8 and MRVP) | 17.5 |

| (9) | Ballpark total present value of long-term award — (7) multiplied by (8)* | $230 million |

* Since inflation is built into the voucher income stream, the discount rate for the real cash flow is low and a straight multiplication is a good approximation of the discounted value.

Project Based Vouchers in Federal Spending Context

All together, cash flow into Massachusetts from federal housing subsidies — excluding mortgage finance, but including the current general Housing Choice Voucher program, legacy housing subsidy programs, and federally supported public housing — adds up to approximately $3 billion annually. (For statistics in this paragraph, see attached spreadsheet.) It is important to distinguish the current PBV program from the historical “project based section 8” program for “new construction and substantial rehabilitation” which was closed to new entrants in 1983. The historical project-based program continues to carry approximately 60,000 units at a total federal annual cost in Massachusetts of $1.2 billion.

The current federal PBV program is a component of the general section 8 “Housing Choice Voucher (HCV)” program — housing authorities are (in general) permitted, at their discretion, to award up to 20% of their allocation of HCVs as PBVs. Under both the general HCV program and its component part the PBV program, at least 75% of new awards must go to ELI households. The current federal HCV program — including both mobile and project vouchers — covers approximately 100,000 units in Massachusetts at an annual federal cost of $1.6 billion.

Given the 100,000 unit scale of the HCV program, the number of annual additional project based vouchers (250 offered in the recent NOFA as discussed above) seems at first glance to be relatively small. However, the HLC directly controls only approximately 22,000 of those vouchers (according to the federal Housing Choice Voucher program dashboard, “the HCV dashboard”); 47 housing authorities (other than HLC) have some PBVs in their portfolio (notably Boston and Cambridge). Additionally, voucher turnover is very slow — only approximately 7% were new in 2023 and average tenure in the program is over 20 years. See attached spreadsheet. The total number of PBVs in the state has grown steadily to almost 20,000 and is now approaching the regulatory cap of 20% of all HCVs (see the HCV dashboard, panel 10), although that cap includes various exclusions (new units for homeless, for veterans, for supportive housing, etc.) which could allow up to 30% of HCVs to become PBVs; additionally, units being converted from older assistance programs to PBV support are excluded from the cap. Many of the PBVs deployed in the state fall in this last category — see, for example, this case study of the Cambridge Housing Authority.

Technical notes on PBV definitions

Voucher programs like Section 8 make payments to property owners to cover the difference between the rent a tenant can afford (defined as a percentage of their income) and fair market rent in the area. Section 8 eligibility and payment amounts are based on income and and rent concepts computed for local areas by the federal Department Housing and Urban Development. These constructs are also used in other programs, including affordability standards for low income housing tax credits and Massachusetts funded voucher programs. This HUD page offers a good overview and this HUD Section 8 guidebook goes deeper. The notes below extract details relevant to the economics of project based vouchers.

Section 8 income concepts

The following income constructs are used for determining eligibility to participate in Section 8 and other programs.

- Area Median Income (AMI) — AMI is the median family income for the area derived from the Census’ American Community Survey with inflation adjustments. The AMI for an area is a single number, but there are multiple approaches to defining area. AMI is a building block for computing income limits.

- Section 8 income limits — in common usage, these are not conceptually distinguished from AMI and they are indeed built from the AMI, but HUD applies a number of complex adjustments to derive the limits. These include adjustments based on comparisons of area median income to other variables — area rents, area median incomes in larger areas, area median incomes in prior years, and poverty guidelines. Additionally, HUD does not use actual census medians for each family size. Instead, HUD builds limits for different family sizes based a set of standardized ratios. For example, Section 8 income limits for a single person “family” are always 70% of the income limit for a 4 person family.

| FY 2024 Income Limit Area | Median Family Income | FY 2024 Income Limit Category | Persons in Family | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH HUD Metro FMR Area | $148,900 | Very Low (50%) Income Limits ($) | 57,100 | 65,300 | 73,450 | 81,600 | 88,150 | 94,700 | 101,200 | 107,700 |

| Extremely Low [30%]* Income Limits ($) | 34,300 | 39,200 | 44,100 | 48,950 | 52,900 | 56,800 | 60,700 | 64,650 | ||

| Low (80%) Income Limits ($) | 91,200 | 104,200 | 117,250 | 130,250 | 140,700 | 151,100 | 161,550 | 171,950 | ||

*ELI is commonly thought of as 30% of AMI, but according to HUDs footnote to this table: “The FY 2014 Consolidated Appropriations Act changed the definition of extremely low-income to be the greater of 30/50ths (60 percent) of the Section 8 very low-income limit or the poverty guideline as established by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), provided that this amount is not greater than the Section 8 50% very low-income limit. Consequently, the extremely low income limits may equal the very low (50%) income limits.”

Section 8 eligibility

Statutory eligibility for section 8 vouchers extends to very low income families (“50% AMI”), low income (“80% AMI”) families in categories approved by the administering agency, and certain additional families. However, by law 75% of applicants accepted must be extremely low income (“30% of AMI”). Additionally, the administering agency may establish preferences among eligible tenants. These preferences given scarcity of voucher funding effectively may become eligibility criteria. For example, under the City of Boston’s voucher administration plan, applicants must be “Priority One” — which generally means displaced either due to a high rent burden (exceeding 50% of income) or life events like domestic violence (some of these preferences are required by federal law).

Section 8 Fair Market Rent

Section 8 Fair Market Rents (“FMR”) estimates are used in computing how much assistance to give Section 8 participants. FMRs are “are estimates of 40th percentile gross rents for standard quality units within a metropolitan area or nonmetropolitan county.” These estimates are based on statutes and regulation which result in the following steps in building estimates:

- Derive 40th percentile rents for 2-bedroom apartments of standard quality from American Community Survey data.

- Adjust for cost factors — recent mover effects, general inflation, rent trends

- Boost region FMR to the comparable statewide FMR (if higher)

- Calculate bedroom price ratios — note that in this respect the FMR calculation differs from the AMI calculation; for FMR, HUD actually uses American Community Survey data for apartments of different sizes instead of standardized ratios for family size (except for single room occupancy and very large apartments).

- Apply limits on rate of decrease from prior year — rents may not drop more than 10%.

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH HUD Metro FMR Area Final FY 2025 & Final FY 2024 FMRs By Unit Bedrooms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Efficiency | One-Bedroom | Two-Bedroom | Three-Bedroom | Four-Bedroom |

| FY 2025 FMR | $2,163 | $2,288 | $2,711 | $3,266 | $3,594 |

| FY 2024 FMR | $2,212 | $2,377 | $2,827 | $3,418 | $3,765 |

Section 8 voucher value computations

The amount that will be paid to a landlord by a tenant holding a voucher is the difference between the defined maximum monthly rent (including utilities and all maintenance and management charges) for the unit and 30% of the tenant households adjusted income.

- In general, the maximum monthly rent is the FMR as defined above, but program administrators may make adjustments to reflect local market conditions and other factors.

- In general, adjusted income is gross income less statutory income exclusion amounts for being elderly or disabled, excess medical expenses, childcare expenses, minors in the household, child support and alimony, earned income of minors. Agencies may establish additional allowances.

Massachusetts voucher programs specifications

The chart below describes Massachusetts’ two statewide voucher programs.

| MA Rental Voucher Program | MA Alternative Housing Voucher Program | |

|---|---|---|

| Statutory Basis | State budget, 7004-9024 | Chapter 179 of 1995, s. 16 |

| Regulations | 760 CMR 49 | 760 CMR 53 |

| Tenant application | Apply | Apply |

| Household Eligibility | Under 80% of AMI, but 75% of vouchers targeted to families under 30% of AMI. | Under 60 and disabled and “low income” (80% of AMI) |

| Rent standard* | 100% area-wide FMR | 110% of area wide FMR |

| Voucher value | Difference between rent standard and 30% of household income | Difference between rent standard and 30% of household income |

| Special program priorities | Homeless. | Homeless. |

| FY2025 legislative annual appropriation | $219,238,574 | $16,403,545 |

Resources

- Spreadsheet of housing statistics

- HUD Resources

- HUD housing choice vouchers

- HUD history of public private partnerships

- HUD discussion of audit of overlap between tax credit and PBV

- HUD HCV Dashboard

- HUD Picture of Subsidized Households

- HUD database of housing developments subsidized under closed federal programs

- HUD PHA Contacts List for MA

- Regulations governing Housing Choice Voucher Program, 24 CRF 982

- HLC Resources

- Additional resources

- Forbes, a Brief History of the Section 8 program

- Congressional Research Service Overview of the Section 8 Program

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Introduction to the Housing Voucher Program

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Project Based Vouchers

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Rental Assistance