Energy Savings Before Mass Save — five post series

When I started into this historical analysis, I thought that I might be able to gain insight into the current state and prospects for improved weatherization of Massachusetts building stock. I hoped that understanding the energy efficiency work that had been done before might set some kind of useful baseline. As it turns out, the historical data we have been able to assemble do not really offer much insight into the future of building energy efficiency improvement. The limited affirmative takeaway from this series is that factors unrelated to building energy efficiency — electrification, burner efficiency, behavior changes — account for the majority, perhaps the vast majority, of the observed decline in residential fossil energy use intensity before 2009.

Long before the Green Communities Act of 2008 reconstituted Mass Save with a muscular energy saving mandate, and even before Mass Save’s original launch in the early 80s as a provider of energy audits, fossil energy use was declining in Massachusetts. During the approximately four decades between the first oil price shock in 1973 and the launch of intensified Mass Save energy efficiency efforts in 2010, fossil energy use intensity declined dramatically in the residential sector in Massachusetts. This post is the first in a five post series exploring how that decline occurred.

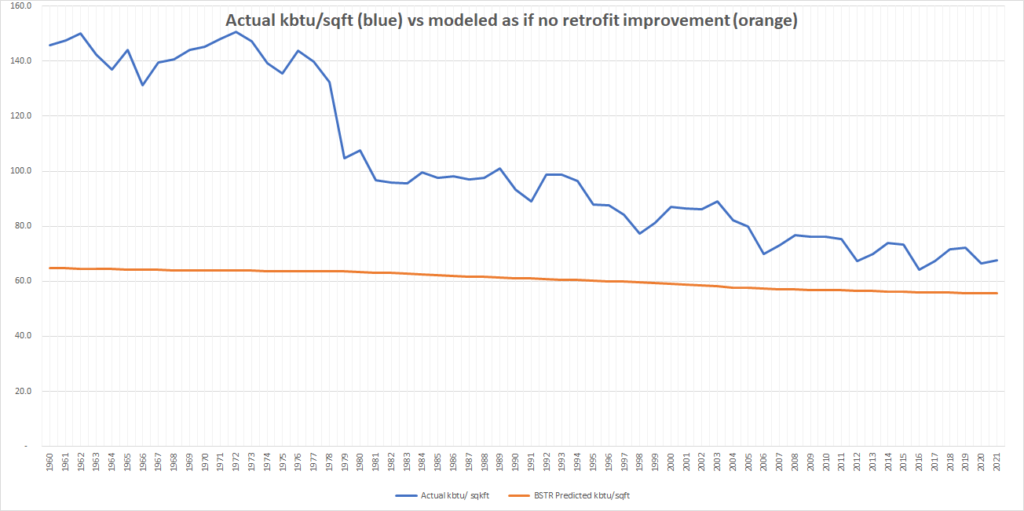

As explained in this discussion of Massachusetts energy use and housing quantity, it appears that the overall energy use intensity of the existing housing stock has declined roughly 50% over the last 50 years. There was a huge drop from 1978 to 1981 which heavily reflected behavior change in response to spiking prices. There was something of a rebound as prices dropped through the 1980s, but after the 1980s rebound, residential energy use intensity resumed its decline. We are focused on Massachusetts data to the extent possible, but homes nationwide achieved significant reduction in energy use intensity during this period.

The chart below shows that actual average Energy Use Intensity (“EUI”, energy used per square foot per year, kbtu/sqft/year) has declined much more dramatically than would be predicted from better new construction alone. Building code changes only affect new homes and they are a relatively small portion of the total.

Chart 1: Historically declining actual Energy Use Intensity vs model based on building code improvements alone — Massachusetts, 1960-2021

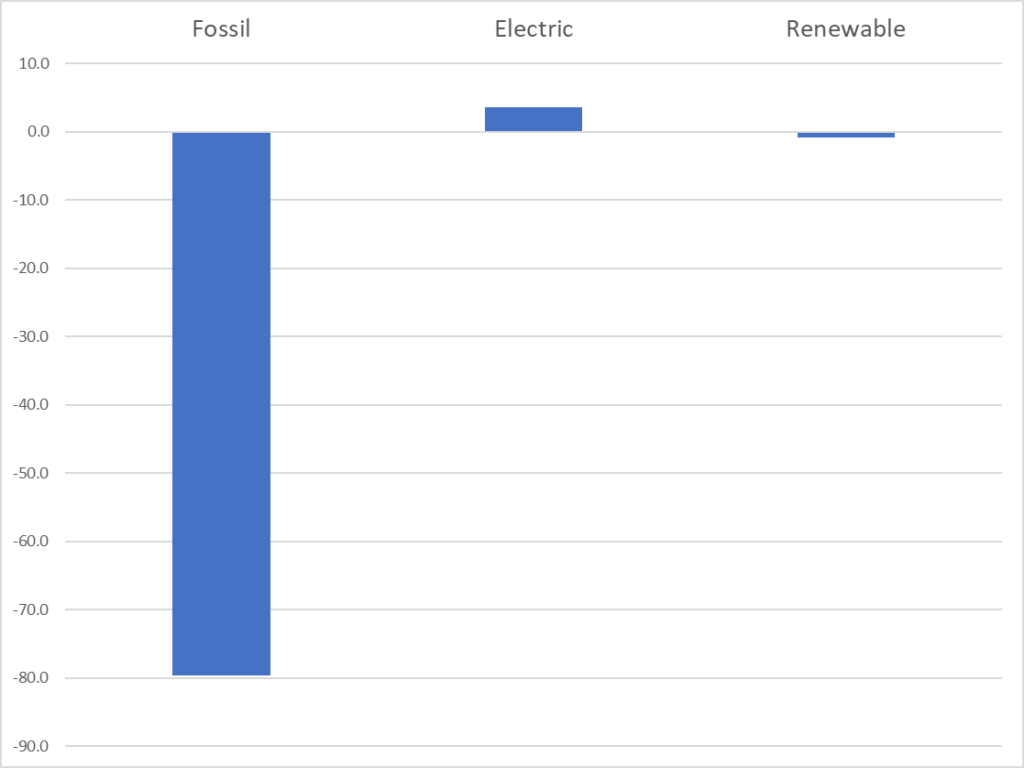

Most of the decline in energy use intensity shown in Chart 1 above occurred within the fossil category; electric and renewable use rose slightly. Chart 2 below compares EUI changes in each energy category. In Chart 2, the starting year is 1972, the year before the oil embargo. Total Massachusetts residential energy per square foot achieved its highest historical level in 1972. The end year is 2009, the year before Mass Save started its first three year plan under the efficiency mandate strengthened by the Green Communities Act of 2008. Massachusetts residential fossil energy use intensity in 2009 (57.1) was 77.9 or 58% below the level in 1972 (135.0).

Chart 2: Change in residential energy use intensity (kbtu/sqft) from 1972 to 2009 in Massachusetts.

In the series of posts linked to below, we consider the following possible explanations for the stunning drop in fossil fuel intensity from 1972 to 2009 shown in the first bar in Chart 2 above

- Shift to electric appliances

- Appliance efficiency improvements

- Behavior changes

- Building envelope improvements

In our analysis, we only focus on fossil fuels and delivered electricity, disregarding renewables. Solar power and geothermal were negligible in the study period (always under 0.1% of total residential site energy). Wood burning EUI surged during the energy crisis years, but ultimately declined along with fossil EUI across the decades so transition to wood burning did not explain reduced fossil use in 2009.

There was zero shift to electric appliances in this period. Even with high oil and gas prices electric was even more expensive. Efficiency improvements and thermal barrier tightening were the keys here.