Listen to a video summary and discussion of this post at this link.

Overview

Until COVID-19 hit, people were driving more each year in Massachusetts. The increased travel meant more congestion.

COVID-19 reduced travel dramatically as more people worked from home and took fewer optional trips. Travel remains down roughly 29% from pre-COVID levels.

Some believe that many workers will continue to work from home, but no one can predict how many. There is no consensus on whether the shift is good thing — it depresses the real estate market and hospitality industries in downtown areas.

From a climate standpoint, the shift is clearly desirable and there is a new conversation we need to have about how and whether to encourage sustained working from home. In his congestion report in 2019, the Governor did propose a $2000 tax credit for employees to encourage working from home, but this idea attracted little interest at the time.

Some have urged that we charge people for driving to discourage driving, for example charging $0.25 per mile driven. Voters are only likely to support heavy charges on driving if we give them good alternatives to driving.

Not all voters have the option of working from home. Nor do they have the option of using public transit. Public transportation accounts for only about 3% of travel statewide.

In the last century, cheap fossil fuels encouraged sprawling suburbs. Statewide, homes and jobs are too widely dispersed and trip patterns too irregular to be well-supported by mass transit, which is only efficient when it serves many people going to the same place at the same time.

Changing land use patterns could make transit use more feasible in the very long run, but most of the buildings that are going to be here 2050 are already here.

Healthy mass transit reduces urban congestion, protects air quality and serves some who cannot afford to drive or are unable to drive. Especially if it is electrified, it can contribute to greenhouse gas reduction. But no one has proposed a scenario in which mass transit displaces a vastly larger share of statewide travel.

If many commuters need to keep driving, we are going to have to make vehicles more efficient. The consensus pathway to greater efficiency, supported by increasing investments by manufacturers, is electrification. For heavier duty vehicles we may achieve reductions through biofuels. These are the main elements of the transportation road map developed by the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs.

There are about 5 million vehicles registered in Massachusetts. To make the necessary contribution to emission reduction through electrification, we will need to sell roughly one million electric vehicles in Massachusetts by 2030. Roughly four million light duty vehicles will be sold in Massachusetts over the next decade, so we are hoping that roughly one quarter of the sales will be electric whereas today only 1% of sales are electric.

The change will not happen by itself. California is moving to mandate specific levels of electric vehicle sales by manufacturers and Massachusetts is legally able to adopt California’s rules. Additional state and federal rebates may also help electric vehicle sales.

The President’s infrastructure bill includes a nationwide network of vehicle charging stations. That will help give consumers confidence that they can drive electric vehicles over long distances.

We are embarking on three decades of accelerated technology change that will require sustained focus from every level of government and huge investment from the private sector. Our new legislation requires more transparency and more frequent benchmarking — we will know very quickly if we aren’t doing enough.

Transportation Emissions

Road travel grew steadily in Massachusetts over the last three decades until COVID-19 hit.

Until COVID-19 hit, people were driving more each year in Massachusetts. The key metric is “vehicle miles traveled” or “VMT”. VMT rose 32.7% from 1990 to 2019 in Massachusetts. VMT per capita rose 15.8% in the same period. VMT per capita rose 7%, from 2010 to 2019. By 2019, congestion was a major public policy issue.

| Massachusetts Transportation Statistics | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | % chg 2019/1990 |

| –Population (thousands) (1) | 6016 | 6141 | 6349 | 6453 | 6548 | 6794 | 6860 | 6893 | 14.6% |

| –Vehicle registrations (thousands) (2) | 3726 | 4502 | 5265 | 5420 | 5334 | 5070 | 5049 | 5061 | 35.8% |

| –Drives licenses (thousands) (3) | 4229 | 4211 | 4490 | 4613 | 4593 | 5041 | 4935 | 4950 | 17.0% |

| –Vehicle miles traveled (billions) (4) | 48.9 | 50.8 | 55.5 | 58.4 | 57.5 | 60.5 | 60.7 | 64.9 | 32.7% |

| –Vehicle registrations per capita | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 18.6% |

| –Drivers licenses per capita | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.2% |

| –Vehicle miles traveled per capita | 8128 | 8272 | 8742 | 9050 | 8781 | 8905 | 8849 | 9416 | 15.8% |

| US Transportation Statistics | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | % chg 2019/1990 |

| –Population (thousands) (1) | 252120 | 265164 | 281711 | 294994 | 309011 | 320878 | 325085 | 329065 | 30.5% |

| –Vehicle miles traveled (billions) (4) | 2144 | 2423 | 2747 | 2989 | 2968 | 3095 | 3212 | 3262 | 52.1% |

| –Vehicle miles traveled per capita | 8505 | 9137 | 9751 | 10134 | 9600 | 9647 | 9882 | 9912 | 16.5% |

- Census data: Statistical Abstracts of the United States; State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2019

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics selected years, Table MV1. Includes all types of vehicles, public or private.

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics, 2019, table DL-201.

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics, 2019, table VM-2. In 2018, MassDOT revised its VMT estimation methodology. For comparison purposes it re-estimated VMT from earlier years. Those re-estimations appear online in EoEEA’s analysis of the transportation sector and are used here for years prior to 2019. The revisions are all upwards — using the VMT reported to the FHA in table VM-2 for 1990 (46.1 billion without the backward revision), VMT would be up 40.7% from 1990.

As travel rose, fuel consumption also rose.

Gasoline consumption increased 13.7% from 1990 to 2019. Cars and light duty trucks got more efficient over the same period, otherwise gasoline consumption would have roughly tracked VMT. If one combines the change in fuel consumption (13.7%) times the national average change in efficiency (18.1%), one gets 34.7% — very close to the VMT increase (32.7%) shown in the previous chart.

| Massachusetts Transportation Statistics | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | % chg 2019/1990 |

| –Gasoline used (millions of gallons) (1) | 2339 | 2441 | 2714 | 2782 | 2734 | 2669 | 2667 | 2659 | 13.7% |

| –Diesel fuel used (millions of gallons) (2) | 267 | 317 | 408 | 423 | 398 | 442 | 438 | 453 | 69.7% |

| Emissions from mobile combustion (MMTCO2E) (3) | 30.5 | 30.1 | 33.6 | 34.9 | 30.3 | 29.5 | 30.5 | n/a | n/a (flat?) |

| U.S. Average light duty vehicle fuel efficiency (mpg) (4) | 18.8 | 19.6 | 20.0 | 20.2 | 21.5 | 22.0 | 22.3 | 22.2 | 18.1% |

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics, 2019, table MF-226.

- Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics, 2019, table MF-225. Very closely similar data appear at Energy Information Administration, Massachusetts Sales of Distillate Fuel Oil by End Use.

- Greenhouse Gas Baseline, Inventory & Projection, Appendix C: Massachusetts Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory: 1990-2017, with Partial 2018 & 2019 Data.

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Average Fuel Efficiency of U.S. Light Duty Vehicles. Miles per gallon.

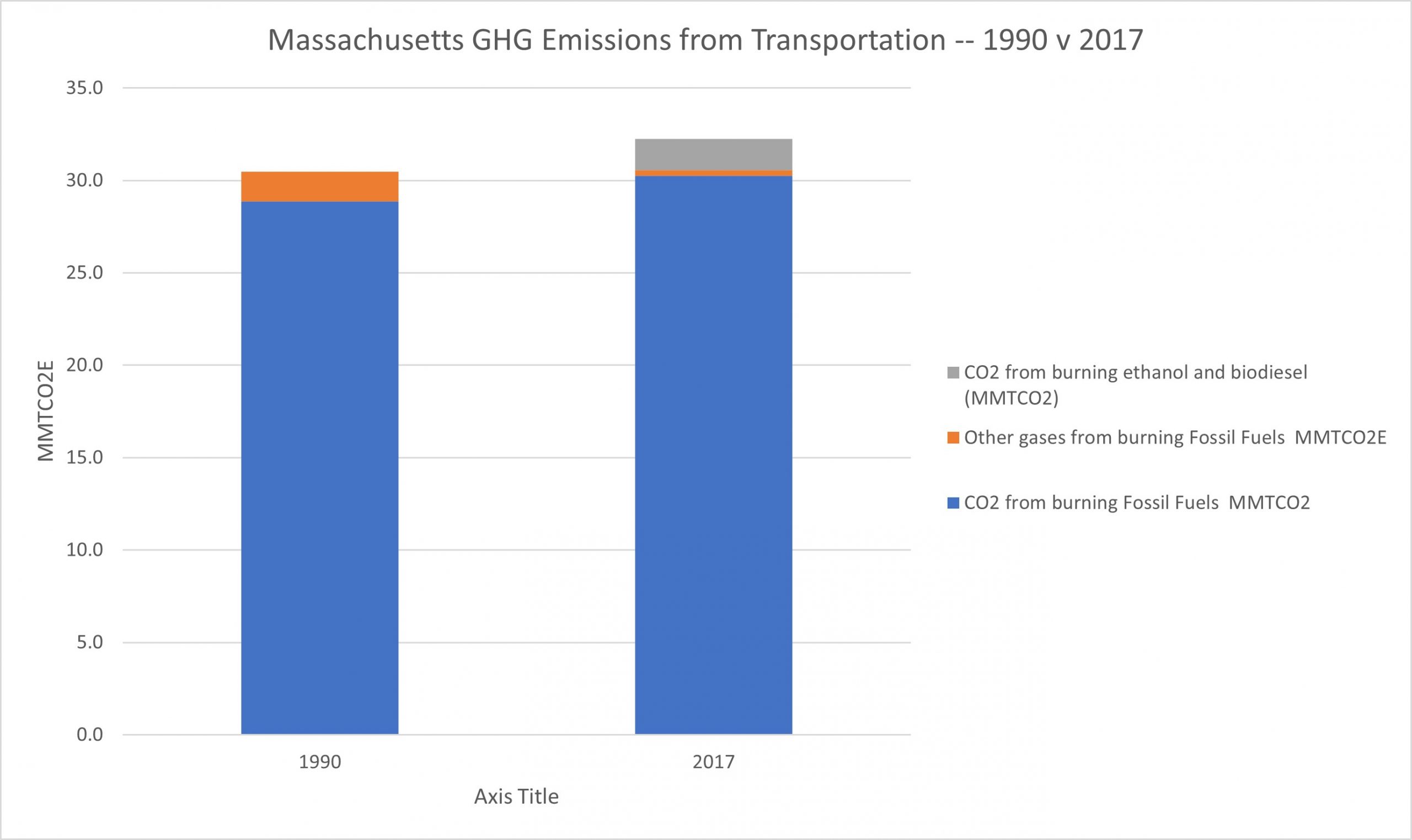

Although fuel consumption rose, reported transportation emissions did not rise.

As shown in the table above, our official greenhouse gas inventory does not reflect an increase from 1990 to 2017, even though fuel burning has increased. Later model year vehicles have improved emissions control systems that do not release as much nitrous oxide. See EPA guidance for competing mobile emissions, Table B-2. Nitrous oxide is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Additionally, most gasoline sold includes 10% ethanol and most diesel fuel sold includes 5% biodiesel (mostly soy oil). We do not count carbon dioxide from burning biofuels as part of our emissions. Arguably, this carbon was recycled out of the atmosphere while the source crops were grown. See discussion in the original baseline development document from 2009 at page 12. But if we counted it, carbon dioxide emissions would be up 10.6% and total emissions (including nitrous oxide) would be up 5.8%.

When COVID-19 hit, travel dropped dramatically.

The graphic embedded below from the MassDOT mobility dashboard shows that statewide weekday travel was down roughly 29% from pre-COVID levels one-year after the start of the pandemic. This will help us meet our surpass our 2020 greenhouse gas emissions goal, but it is not clear how long the reduction will last.

Statewide vehicle miles traveled.

Source: MassDOT mobility dashboard. Link to full screen chart. Link to static image of chart as appearing on April 3, 2021.

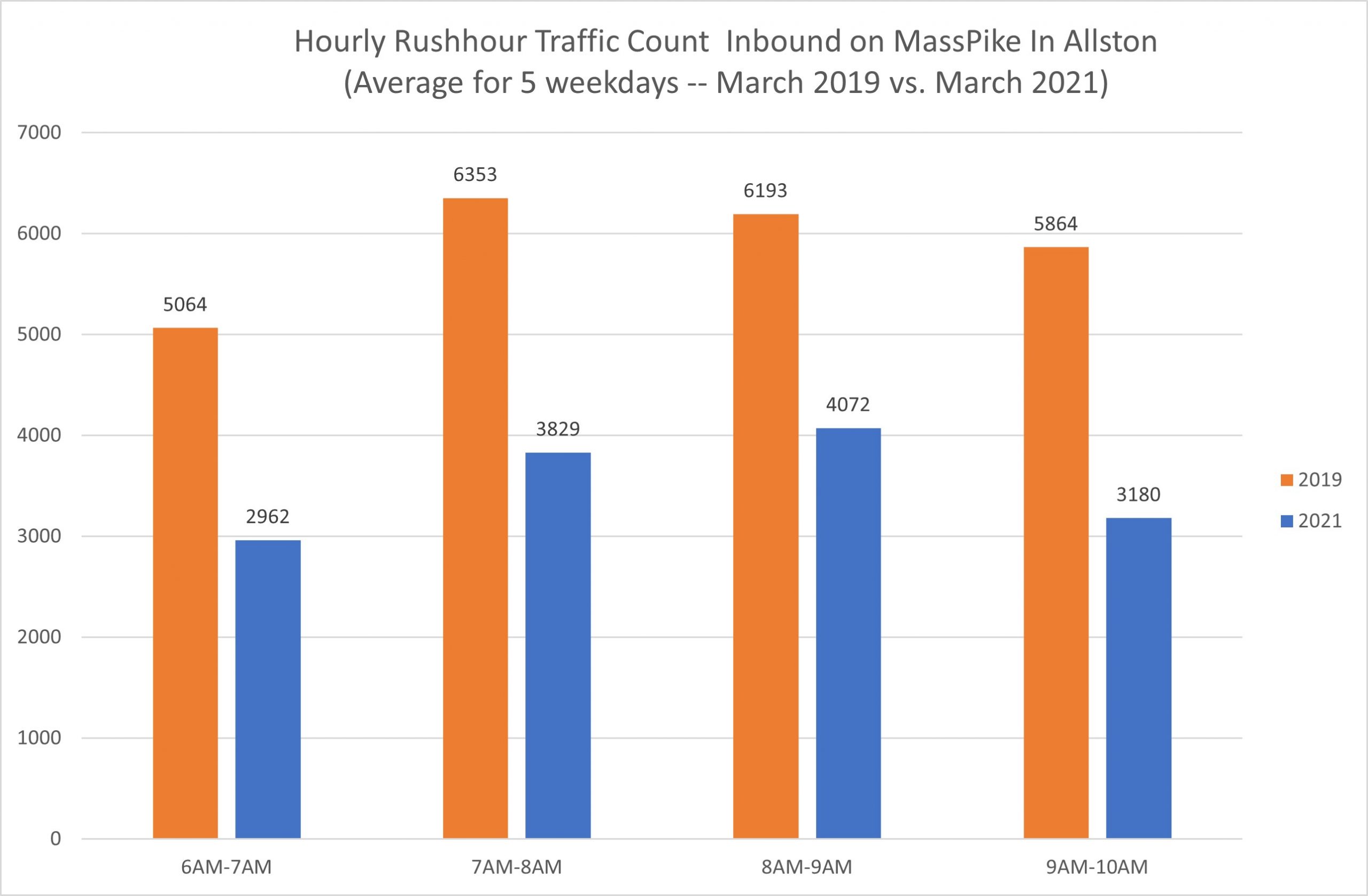

Inbound traffic on the MassPike inbound in Allston is down 40% at between 6AM and 10AM, indicating that the greatest drop in volume is among the commuting professionals who work office schedules. The traffic reductions are greater early and late in the morning, showing that the true rush hour is shorter.

Reducing Driving — Alternative Strategies

If businesses continue to support working from home, they will help to greatly reduce emissions.

Working from home cuts travel at the most congested times of day. MassDOT proposed a tax credit for working from home in their 2019 congestion report (p. 77). By cutting travel, working from home also cuts fuel consumption and emissions.

The pandemic has started a newly serious conversation about working from home. Many employers and employees found that with the available technology, working from home has big advantages. While there is still a lot of debate and uncertainty, the emerging consensus seems to be that many workers will continue to work from home for at least some of the time.

The factors that will determine work from home rates over the coming years go deep into the structure of the workplace. It may not make sense to attempt to influence the transition through public policy. Moreover, some areas will be hurt by the shift to work from home, so a consensus on interventions may be hard to attain. The clear public policy priority is to assist those dislocated by the work from home shift — notably service workers in downtown areas.

Traditional strategies for reducing travel offer modest additional emissions reductions.

A recent study by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council compared the effects on vehicle miles traveled of different combinations of land use change and charges on drivers to discourage driving. The study does not factor in the effects of the pandemic.

Land use patterns have a big influence on travel and related emissions. Generally, people who live in urban areas drive much less than those in the suburbs or rural areas. Unfortunately, land use patterns change much too slowly to make a big difference over the 30-year time frame of our climate plan. The graphic above shows that smart growth policies could cause a 2% reduction in VMT growth over a 20 year time frame. Most of the buildings that are going to be here in 2030 or even 2050 are already here. There are 2.9 million housing units in Massachusetts and we have built an average of 152 thousand units per decade since 1990.

Costs of driving can also influence travel and related emission, but they have to be unacceptably high to make a real dent. MAPC’s modeling (shown in the graphic above) indicates that an aggressive combination of tripling the gas tax, charging drivers for coming in to the city at rush hour, and additionally charging all drivers 25 cents for every mile driven would be required to cut driving 10 or 20% instead of merely blunting increases. The voters recently rejected a very modest increase in the gas tax.

Given that many workers now have the option to work from home, new research might show that driver charges could change commuting patterns more dramatically. But the increased costs would fall heavily on those unable to work from home, who are also likely to be lower paid workers.

Mode shifts to mass transit, biking and walking offer modest additional emissions reductions.

Choosing to travel with others, whether in a shared ride or in mass transit, always saves emissions. Biking and walking eliminate emissions. Healthy mass transit is critical to controlling urban congestion, especially at rush hour.. If it is well loaded, it can make a contribution to greenhouse gas emissions reduction. If it is electrified, it can contribute to air quality improvements. Those living in dense urban areas have a viable option of living car-free and some have no choice but to depend on transit.

However, from a statewide perspective, driving accounts for most of the passenger-miles traveled.

| Massachusetts Statewide Travel Estimates | |

| Annual passenger miles traveled by automobile | > 44 Billion |

| Annual passenger miles traveled by public transit | ~ 2 Billion |

| Bike/Walk miles traveled — not known | << 1 Billion? |

No one has developed a planning scenario in which alternative modes displace a vastly larger share of vehicle-miles-traveled statewide. In the last century, cheap fossil fuels encouraged the build out of sprawling suburbs. Our homes and jobs are too widely dispersed and our trip patterns too irregular to be replaced by mass transit which is only efficient when it serves many people going to the same place at the same time; lightly loaded mass transit vehicles are not energy-efficient.

Only through widespread adoption of electric vehicles can we reach ‘net zero’.

Widespread working from home could take us a long way towards our 2030 goal of a 33% cut from current emissions level (50% from 1990). But we have to shift to zero emission vehicles to reach our 2050 goal of zero net emissions and we likely need to start the shift now, even to achieve our 2030 goals.

That conclusion flows from the limits of available alternative strategies as outlined above. It is confirmed by the much more sophisticated analysis that our Executive Office of Environmental Affairs did in developing their transportation road map. Even for the 2030 goal, EoEEAs analysis concludes that widespread vehicle electrification is the central strategy.

| 2030 Emissions Strategy Element | GHG Emissions Reduction by 2030 |

| Electrify 750,000+ light duty vehicles | 5.1 – 5.4 MMTC02E |

| Biofuel and electrification for heavy duty vehicles | 1.8 MMTCO2E |

| Reduce travel through smart growth and incentives | 0.8 MMTCO2E |

| Other investments in clean transportation | 0.1 MMTCO2E |

| Total Emissions Reduction in Transportation Sector | 7.8 – 8.1 MMTCO2E |

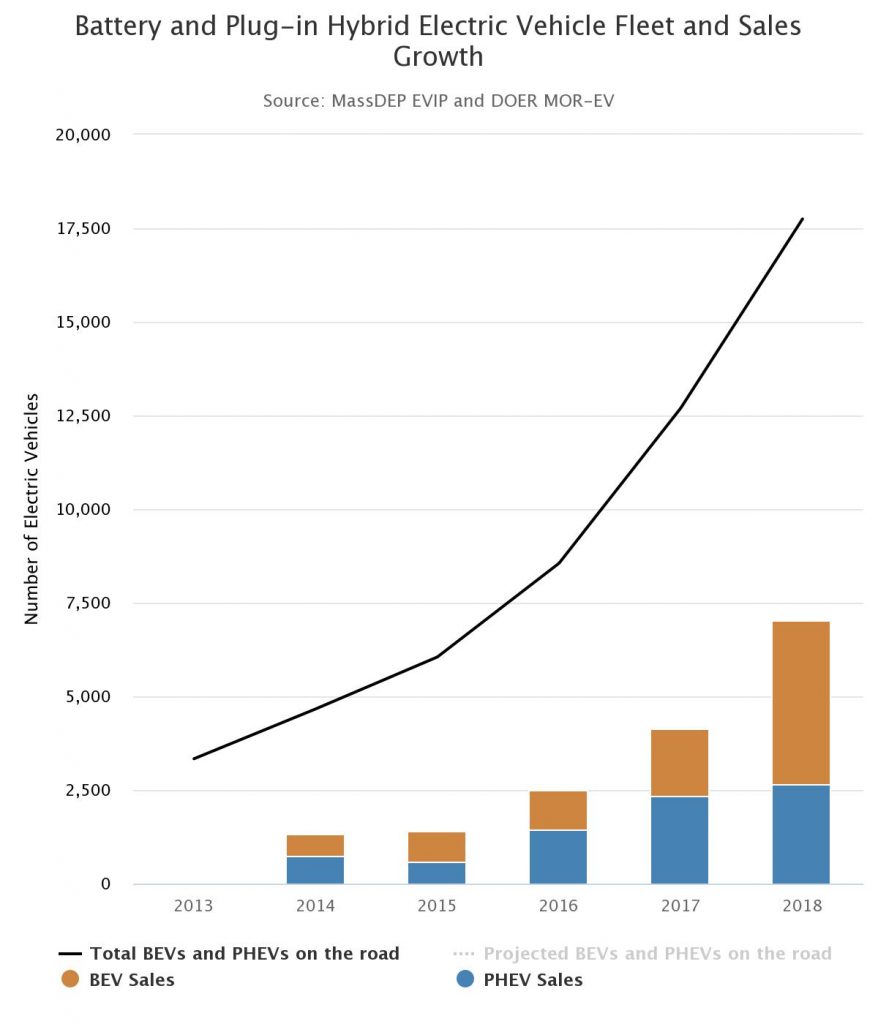

The shift to electric vehicles will need to accelerate from current trends.

EoEEA’s plan contemplated a 45% reduction from 1990 levels by 2030 where as the new statutory goal is a 50% reduction. The deeper statutory goal will require a higher number of zero emission vehicles. Depending whether working from home offers sustained emission reductions, perhaps 1 million or more out of the approximately 5 million vehicles on the road will need to be ZEVs.

The graphic above shows that the current volume of electric vehicle sales is a tiny fraction of what it will need to be to achieve our emissions goals. Three or four million light duty vehicles will be sold in Massachusetts over the next decade. (Estimate here.) So, we are hoping that more than one quarter of the sales over the coming decade will be electric. One quarter of sales being electric over the whole decade is consistent with half of sales being electric in the final year of the decade. Currently sales are one or two percent electric. The Deloitte projection below would put sales through the decade at about half the level we need. Other analysts are more optimistic. For more discussion of trends, see the Governor’s Commission on the Future of Transportation report, Volume II. See also the transportation sector technical report accompanying EoEEA’s decarbonization roadmap (page 11). A National Academy of Sciences report suggests a positive scientific consensus as to the feasibility of zero emission vehicles (battery electric and also fuel cell vehicles).

We are heavily dependent on the creativity of the auto manufacturers, but there are three major ways that we can increase sales.

- Regulatory mandate on auto manufacturers: California is moving to require specific levels of electric vehicle sales by manufacturers and Massachusetts is legally able to adopt California’s rules.

- Incentives to purchase new electric vehicles. The state already provides rebates up to $2500, but combined state and federal incentives could increase. Some believe that EV’s will reach cost parity with ICE vehicles soon.

- Infrastructure support for electric vehicles to complement private investment: The big news is the President’s announcement of a proposed infrastructure bill that will include building out a network of vehicle charging stations. That will help alleviate consumer concern about running out of battery range.

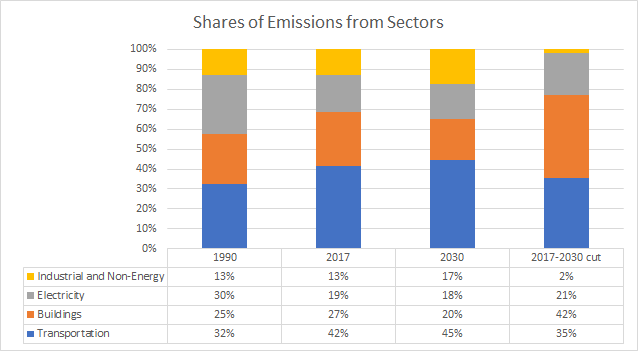

Even with the hoped for rapid adoption of electric vehicles through 2030, transportation will still be lagging other sectors in decarbonization (according to EoEEA projections).

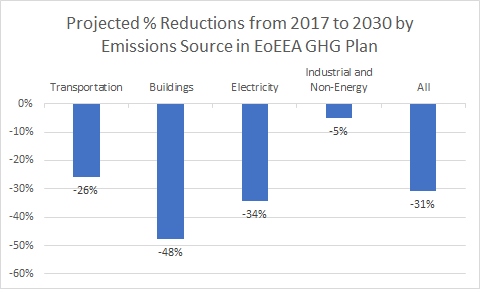

As noted above transportation emissions have been unchanged over the past three decades (pre-COVID). Arguably, they have risen, depending on how one does the emissions accounting. As other sectors have made progress, transportation has become a larger share of emissions, going from 32% in 1990 to 42% in 2017 to a projected 45% in 2030 in EoEEA’s plan for achieving a 45% reduction by 2030 (not as deep as the 50% now required by statute). Transportation would only account for 35% of the reduction from 2017 to 2030.

Looking that the analysis another way, EoEEA is projecting deeper 2030 reductions in the building and electricity sectors than in the transportation sector. EoEEA’s strategy analysis weighed a range of economic factors in striking this balance, and one may read the chosen balance as a finding about the relative difficulty of each cut. Cutting building emissions by 48% is comparable in difficulty to cutting transportation emissions by 26%. Cutting electricity emissions by 34% (while increasing output) is comparable in difficulty to cutting transportation emissions by 26%.

The focus on electric vehicles raises an equity issue.

To the extent that electric vehicles remain expensive compared to other cars, public support for them (in the form of subsidies for vehicle purchase or for charging systems) arguably benefits more affluent people. This is not an argument against support for electric vehicles. Emissions reductions benefit everyone. But we need to make sure that our portfolio of investments also includes measures that benefit lower income communities, for example electrification of highly polluting buses, or maybe electrified , autonomous vehicles that provide mobility as a public service.

The key assumption is that electric vehicles will draw their charge from renewable power.

The transition to renewables for electric power generation is the foundation for the larger strategy. The grid transition is made more difficult by the expanded demand projected from both electric vehicles and electric heat pumps. More on that transition in a future piece. Electric vehicles are not the only possible zero emission vehicles, but they are getting most of the industry attention and investment.

Highlights from Comments

A number of people have made good points in response to this piece. Please see further below. I want to respond on a couple of themes.

Working from home

Chris Dempsey of T4MA makes the point that working from home may not actually reduce vehicle miles traveled in the long run. (Mike Small also makes this point.) It all depends on how other travel changes and on how residency patterns change. Even if people are commuting less, they may drive more for other purposes. Telecommuting is most likely to increase total VMT if people move out to less dense areas where they need to travel further for necessities, but may decrease VMT if people maintain their residence while changing commuting patterns. All of that agreed, one thing is clear: working from reduces congestion at rush hour and so reduces the pressure to find new solutions for rush hour traffic.

Fuel Efficiency

While wide conversion to battery electric vehicles appears to be necessary even for 2030 goals, it does make sense to encourage any vehicle that is much more efficient than the current fleet in the medium term. Plug-in hybrids are included in the state’s rebate program.

We will probably want to limit our use of subsidies to electric vehicles, so our other main tool is regulatory efficiency standards. Fleet fuel efficiency standards have made a big difference, and there is some room for improvement in internal combustion engines, but Massachusetts cannot create its fleet own efficiency standards. Fleet fuel efficiency standards are governed by a combination federal law and more stringent California laws (which Massachusetts can elect to enforce). The state appears fully committed to continuing to embrace strong California standards. See Clean Energy and Climate Plan at page 21.

It does seem clear that (a) deep reductions require movement away from internal combustion engines — the remaining efficiency gains available from design improvements to internal combustion engines are limited (see NAS video at 15:00); (b) battery electric vehicles are the main alternative that industry is investing in — hydrogen fuel cell vehicles would require a completely new fuel delivery structure and are receiving less attention than battery vehicles: we may not have a lot of charging station, but we do have an electric grid to support them.

Significant cost of subsidy

As Bill Green points out: A $2500 rebate for each of 1 million vehicles adds up $2.5 billion over ten years. Many project that EVs will become more competitive in upfront cost and that subsides will become less necessary to encourage adoption — the key variable is the cost of battery storage. Certainly, if subsidies remain necessary at a large scale, we need to think about targeting subsidies by buyer income and also likely by vehicle use.

Autonomous vehicles

Dean Murphy, by email, shared several links about autonomous vehicles: Forbes, ScienceDirect, SemiconductorEngineering, McKinsey. “Autonomous, Connected Electric Shared (ACES)” vehicles, like Uber but without drivers, may play a big role in future transportation. ACES vehicles could accelerate the transition to battery electric vehicles since people would not have to invest in their own new vehicles.

ACES vehicles will likely play the biggest roles in dense areas — that is certainly the pattern with Uber and Lyft today. As much as they changed downtown night life, the TNC companies accounted for only 91.1 million trips (1.2%) out of 7.1 billion stateside passenger trips in 2019. The trips were relatively short at 4.1 miles, so that loaded TNC trips accounted for only 0.5% of vehicle miles traveled statewide in 2019.

Single occupancy shared vehicles do not necessarily reduce VMT: Uber and Lyft have been perceived as increasing congestion unless occupied by more than one person at a time.

It took well over a year from when Cornerstone Village Cohousing on Harvey St., North Cambridge approved the installation of six EV dual-port charging stations in our parking lot. Our contractor was always ready and willing but Verizon and Eversource had a “when we have nothing else to do” approach to their part of the work. The installation of charging stations throughout the state has to be made more of a priority by the utilities.

Municipalities have little to no leverage over utilities even when it comes to enforcing settled regulations. Watertown experiences this regularly every time Verizon lays waste to a vast swathe of trees. If the state does make it easier for municipalities to compel compliance and attach company assets via a simple procedure, all of these plans and more will add up to nothing.

Does NOT

That is distressing to hear about the delays in getting the EV chargers at Cornerstone. We should be doing more to get the utilities to treat these installations as the priority it should be. I have been working to understand why the city chargers are being installed relatively slowly. Getting the electric grid and capacity in place is key.

I see no mention of bicycles on this article, and they’re clearly part of the solution. Aside from walking, cycling is the single most effective way to address the pollution problems that arise from our transportation choices. Even electric vehicles, welcome though they are, are not as helpful as switching to modes where people can get where they need to go under their own power: on foot or on pedals. A proposal that omits simple good old fashioned bikes is not a proposal that can be taken seriously.

I agree with this and would add ebikes. They’re much more efficient than electric cars and can cover greater distances than bikes alone, cutting out even more automobile trips.

There are several suggestions to consider for environmental improvement with regards to transportation.

1.) Prioritize the project to electrify the commuter rail routes and phase out the use of the diesel engine / locomotives.

2.) Consider expanding electrified commuter rail service between Western Massachusetts and Boston. This will alleviate a significant amount of automobile congestion on the turnpike for travelers between these points whether it is for leisure or business.

3.) Consider expanding existing transportation alternatives. More transportation alternatives will provide incentive for people to utilize public transportation rather than automobile. One option project example would be the reconsideration of expanding the blue line into Lynn as well as expanding it to Charles MGH to allow one-stop connection service to the red line. North shore residents will also have greater access not just to downtown but to connecting points in other areas of the state with the blue line expansion and connection / linkage to the red line.

4.) Lobby our congressional representatives to press for legislation and regulation for increased mileage and fuel efficiency for automobiles. The argument that people require automobiles is indeed quite valid. Thus more efficient automobiles would help contribute to environmental betterment.

5.) Expand the commuter rail service full-time to Cape Cod / Hyannis. This will alleviate any traffic and congestion going to the cape for residents, visitors, and employees. The expansion of the commuter rail to Hyannis and perhaps beyond to points such as Orleans or even the outer cape may be a viable alternative to the often congested Route 6 that provides horrible congestion and unfavorable environmental impacts on the Cape. This will also alleviate any reliance on diesel bus service. Plymouth and Brockton does not seem to be interested or planning to resume its prior service levels but the demand and need remains and this might be a perfect opportunity for electrified rail to the cape full time.

Mr. Ciszek, I agree with your suggestions.

I’ve been searching over the past year for a small electric van to use in my business. There aren’t any available in the US. The only electric pickup I could find is the tiny Pickman, which is barely street legal. But you can buy an electric van easily in Europe from Ford, Mercedes, or Nissan. How will we ever reach these lofty goals if the electric vehicles people like me way to buy aren’t available in this country?

This is beyond the scope of this post, but I was wondering if some of the gains from working from home are somewhat offset by heating and air conditioning residences during the hours that would have been spent in an office.

I’d like to see a study on this, but assuming the heating and A/C needs are similar in-office vs home, there is all the savings from commuting being cut out of the equation. Additionally, at home I generally have the windows open 6 months out of the year for airflow with no heat or AC running, whereas in an office environment, the windows generally don’t open, and an HVAC system is running year round to circulate air no matter the temperature outdoors.

How about put pressure on the Chinese government to stop building new coal, but more importantly PAVE THE ROADS. Your fake progressive policies are helping no one besides rich Tesla owners all while this place is falling apart. Have fun when your tax base leaves.

EVs are good. We want those. Please pave the roads so we may drive with them. Also please entertain dissenting views in order to make your excellent climate case even stronger. Thank you, thank you so very much.

absolutely

No sense questioning official Govt/Corporate dogma. Closing all our coal fired plants with excellent scrubbing technology only to open them in China with no scrubbing technology makes perfect sense. This is settled science. On with Agenda 2030 and the 4th industrial revolution. We should be boycotting products made in China. CCP treatment of Uighurs, Christians, Tibetans, etc. Actual slavery and torture going on and everyone turns a blind eye…too concerned with crippling our Country with UN globalist schemes.

yup

Having any additional tax on ICE vehicles will just tax those who can not afford to buy the over priced electric vehicles. It will also likely contribute to a significant inflationary push because it will make everything cost more.

The key to success is investing in how to make home charging stations a free or cheap installation.

Also the effort to have the best battery tech for our homes and mobility devices.

Right now there are monopolies that are charging way more than they should in my opinion for electric transportation devices. Make the electric infrastructure equal or cheaper than ICE devices and you won’t need penalty taxes. If we can do it for the vaccine, we can do it for electric vehicles.

Good points. Should also be noted that China dominates the global battery supply chain. Do we really want the CCP to have even more control of this country?

Hi Will, as usual, your attention to this is appreciated. Your meeting with Senator Barrett was very informative as well.

In terms of electric vehicle charging stations, there are only a few in the Cambridge/ Watertown area. (Porter Square’s is free, and almost always taken, as is the Watertown Library…). I am disappointed that Whole Foods, for example, has not taken a lead on providing charging stations in their parking lots. How would one go about reaching them to press the issue? They have all the resources, and yet lag behind egregiously in these urgent matters.

Thank you for this post! I agree that this only works to the degree needed if we are able to transition to renewables, so I am looking forward to your future piece on that. I also agree that equity needs to be considered here and I would love to see a fully electrified and widely accessible bus fleet with expanded and optimized routes.

Today high mpg hybrids (eg Prius) are very attractive way to cut greenhouse gas emissions, but in longer term EVs will become the more effective solution to greenhouse gas emissions from private cars: It is going to cost society some real money to make the change to EVs, though the societal benefits outweigh the costs. Legislature (or executive branch through regulation), together with federal policy, is going to determine how the cost gets spread across society. Forcing a certain % of new cars sold to be EVs is problematic: the car dealers will need to raise conventional car prices to make enough money that they can sell the EVs below cost to achieve the goal. Possibly people will buy gasoline cars out of state where they will be cheaper. A better version (harder to dodge by buying out of state) would be to raise sales/excise/use tax on gasoline cars and lower it on EVs, to keep revenue neutral but give EV a de facto subsidy. Current EV subsidy (from income and general sales tax) is also reasonable, maybe less harmful to low income car owners. Subsidy will become a significant part of state budget: $3000 x 1 million EVs = $3 billion over 10 years. Maybe (?) by 2030 a subsidy will no longer be necessary because cost of owning an EV will be comparable to cost of owning a gasoline vehicle – but maybe it will need to continue because customers like the quick refueling with gasoline? 50% target is really challenging: in addition to higher CAFE standards and lots of EVs in new car mix, the used car market is going to have a lot of low mpg cars. May need a way to get low mpg vehicles off the road?

Where would what Fred Salvucci said in the meeting with Senator Barret about getting people out of cars in the short term fit into this analysis? I don’t doubt that electric cars will need to be most of the solution, but I’m have trouble letting go of the idea that mass transit will need to be a bigger part than you imply. But I don’t have any rigorous analysis. Well, being a bit flip, if mass transit is only 3% of vehicle miles traveled what percent of vehicle miles are currently traveled in electric vehicles? I.e. either would need to grow by leaps and bounds from current levels to make enough difference. But yeah, even for me it’s easier to imagine people switching to electric cars than finding seats on transit for ten times as many people and having them actually willing to take it.

We’re going to need energy storage. Maybe in addition to credits/subsidies EV owners can make money selling battery current back to the grid at peak load.

Regarding working from home, giving the employee the tax break doesn’t make sense to me. The employers ultimately call the shots on how much remote work is allowed. Also, supposing remote work is here to stay in some major way (who knows if that’s likely, I have my doubts) has anyone studied the non-transportation effect on emissions of people who were living in multi-unit buildings shifting to stand alone suburban homes. To encourage remote work, is it not to encourage more sprawl, fat lifestyles with bigger houses with more room for consumer goods, and more deforestation? The commuting emissions might be larger but any such lifestyle effects should be accounted for and offset the apparent gains. And if we’re going to live spread across the state then the 15% CO2-eqv. capture adjustment we’re counting on for net zero may have to come from tricky engineering rather than from more trees.

Why did VMT per capita increase over the last twenty years? Does this plan account for the possibility of a similar increase in the future?

Putting the responsibility for fixing a systemically-caused problem on individuals isn’t sustainable, and almost any way to out pressure will lead to really harming vulnerable individuals and communities.

It’s a pretty glaring flaw when a plan casually lobs heavy financial burdens at workers while bowing, scraping and hat-tipping to their employers.

Corporations determine whether employees work from home. Not employees. And research has shown that companies often make those decisions for the most trivial, egotistical reasons; e.g., corporate headquarters are frequently relocated to wherever the CEO wants to live.

Despite the measurable financial success of working from home, everyone is starting to hear noises from their senior managers suggesting that “it’s time to bring people together” and “we need to act as more of a team.” For those who do not work in or with corporations, allow me to translate: “F@@@ employees, shareholders and the environment. What’s the point of being in the C-suite if I can’t force the minions to suffer while I watch from above?”

The idea that the one idea that’s actually working can’t be pursued because it would annoy the donor class is absurd.

We should start by discouraging driving in areas where public transportation and cycling are good alternatives. The Boston metro area can do more than it’s fair share to reduce VMT. There are few neighborhoods that cannot be reached by public transportation and bike (or a combination of both). Start by eliminating/reducing parking in new and remodeled buildings. Upzone cities and towns to make it easier to build dense housing mixed with neighborhood amenities so that people don’t need cars to begin with. Electrification of the vehicle fleet is silly and classist as long as electric cars costs tens of thousands of dollars and our electric drug runs on fossil fuels.

Non-starter for families, busy working people, and older folks. This whole trend of trying to control other people’s lives is most off-putting, and people will not put up with it.

There’s nothing wrong with encouraging greater neighborhood walkability. People can’t choose to walk to their corner store if there’s nothing there.

If post Covid turnpike traffic is anything like pre-Covid, “light duty trucks” and passenger cars are not the main problem. The vast numbers of heavy commercial trucks are the ones spewing exhausts and are a large proportion of the traffic. While trying to drive among them, I kept wondering why they were no longer on the railroads the way they are in east/west New York. Railroads have largely been given away in MA. How will that sector of heavy duty consumption be addressed to meet our goal? Can it be?

Heavy duty trucking is a significant contributor to CO2 emissions, but it is in some ways even harder to reduce than passenger cars since truck engines are already about twice as fuel efficient as cars. Many researchers including me are trying to develop workable low carbon alternatives for trucking, but they are not commercialized yet so probably those will not have a big impact until after 2030.

“ In the last century, cheap fossil fuels encouraged sprawling suburbs. ”

Better transit, electric buses, wide implementation of bus lanes (even the one proposed for the Access Ramp to the Alewife T), priority to buses at stop lights, and continued better cleaning of buses, all and more are the future of less emissions.

“In the last century, cheap fossil fuels encouraged sprawling suburbs.”

Last century, it was thought that the interstate highway system, enacted by President Eisenhower was a significant contributor to suburban sprawl. As an example, when a third(?) lane was added to Route 93 into New Hampshire, suburban growth built houses in Massachusetts and into New Hampshire.

“ In the last century, cheap fossil fuels encouraged sprawling suburbs.”

Is the new interstate, electrified passenger trains? That would require an efficient and wide scale track replacement, electrification, and operating capability. Competing companies would energize the design and construction just as Lincoln energized the construction of the Trans continental railway, during the Civil War(!), by issuing two contracts: one to build east form California, and one to build west. The more built, the more profit.

We need both the carrot and the stick to get more ridership on public transportation. It needs to be free downtown like it was for most of last year in Seattle. Commuters buy monthly passes so this won’t inordinately impact revenues there. But even if it did, the MBTA runs a deficit every year and if ridership continues to drop it will be difficult to justify it’s existence.

Additionally, shut the fastpass readers off between 4 and 6 or 7 am. Get drivers on and off the highway earlier.

It is way too late for false equivalencies in public discourse. We need big, bold plans. We are well over 350 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere today. A climate catastrophe is a virtually surety. We need to lessen the impact.

Will wrote that “we need to make sure that our portfolio of investments also includes measures that benefit lower income communities.” MassBudget makes a great case that bus fares are a regressive tax and should be eliminated https://massbudget.org/2021/03/24/free-buses-advance-equity/

This is an extremely smart white paper. Just a couple of supplemental thoughts.

First, it’s a big plus to increase patronage on existing transit, but new transit lines are very rarely conducive to emission reduction, for two reasons: (a) new suburban lines tend to be lightly traveled, and (b) if new right of way construction is required (rail or road), that in itself is very energy intensive, and can take many years to offset even if (as is unlikely) the new transit lines themselves attract enough traffic from the roads to be valuable in emission reduction terms.

Second, I would not count heavily on tax increases to suppress motor vehicle travel. We’ve seen over the past fifty years that such tax increases are too unpopular to be enacted in the U.S., and there is no evidence this is changing. Congestion pricing may become feasible as a means of reducing congestion itself in a very few very high density urban locations (eg, Manhattan), but this is not likely to have significant effects on overall emissions even at metropolitan scale. So the predominant strategies will have to be support for innovation and investment in renewable energy and vehicle electrification, along with tax and other incentives for buyers to purchase such vehicles.

Thanks very much indeed, Will, for taking this set of issues so seriously and distributing this excellent white paper.

I totally agree. High gas or mileage taxes will slightly reduce miles traveled but even very high gasoline prices as in Europe do not change personal car behavior that much. Way more effective to increase vehicle efficiency, i.e. reduce CO2 emissions per mile traveled. Simplest cheapest way in short term is imposing tighter CAFE or similar standards. But looking longer term, electric vehicles are a better choice, particularly if the state is really going to decarbonize the grid eg by building a huge number of windmills.

I agree with the esteemed Professor regarding the quality of the analysis and his suggestions. Some additional thoughts on strategies, many of which your analysis already touches on:

– More frequent efficient bus travel on heavily used corridors, preferably with electric buses (e.g., BRT).

– Changes to zoning to encourage denser settlement patterns and Transit-Oriented-Development are great, but as your paper points out, will take time to have any significant effect.

– If we could eliminate 20% of commutes through work from home it could really be a gamechanger in terms of congestion and emissions, although some of the VMT will probably just get spread out throughout the day and across the region.

– Operational improvements (e.g., synchronized lights, improved incident response, managed lanes) that help to manage demand and improve efficiency along corridors can also help reduce emissions.

– Increased use of micromobility (shared e-bikes, scooters – preferably dockless) might help on the margins.

– Consider ridehailing, which may have the net effect of increasing VMT. Are there regulations that could encourage Uber and Lyft drivers to use electric vehicles?

As usual, a very substantive analysis. I am grateful that you are bringing serious thinking about how to achieve the 2030 goals of net zero inn transportation. You make a good argument that a statewide approach MUST focus on electrification of cars. However, as you noted, driving habits and needs in densely populated areas are different from those in more rural areas. Limiting ourselves to a single statewide approach that does not distinguish these differences will dilute overall effectiveness. Is relying solely on electric cars and shifting habits of office workers enough? In any case the conversion to electric vehicles calls for enormous as yet unspecified new resources, and directing some of these resources to more robust electrified mass transit and regional transit systems (with its benefits to equity and quality of life) may be a better investment and should certainly be part of any statewide strategy even if selectively applied. I urge you to incorporate urban/suburban/rural options as part of a statewide approach.

I am gratified to read your well reasoned and informed paper. The imperative for the short term, post covid, is to encourage people to resume using public transportation. Emplyee discounts and a substantial raise in gasoline taxes might help.

The gas tax would also enhance the sale of electric vehicles. The legislature could also do more to encourage sensible zoning of village nodes. What about a requirement that newly constructed parking garages supply recharge stations.

Thanks, Will, for the detailed, thoughtful and well-reasoned analysis.

I’m a physicist and teach a course at Tufts on the science of sustainable energy, and would add a few points:

1) Yes, electrification is key, but your last, brief paragraph is the crux: We need a VAST expansion of carbon-free electrical generating capacity — we don’t just need to replace the fossil-fuel-powered generation that already exists, but much, much more to support all the new electric vehicles, heat pumps, etc. Reducing consumption is good, but it can’t get us anywhere near where we need to go.

2) There are only three technologies capable of providing carbon-free electricity at the necessary scale: Wind, Photovoltaics, and Nuclear. Everything else is a niche technology at best. Whatever balance we choose among the three, the rate at which we expand their capacity needs to accelerate by a factor of ten or more. It will require a national program of investment on a scale never seen in peacetime.

3) Biofuels are largely a mirage. Photosynthesis is very inefficient at converting solar energy into usable chemical energy, and modern agriculture is so fossil-fuel intensive that it’s unclear whether growing crops for fuel saves any carbon emissions at all. Biofuels from waste are better, but not sufficiently scalable to have a large impact.

I agree. Biofuels maybe have sufficient scale to cover aviation fuels, but not nearly enough to provide a big part of the huge amount of fuel needed for trucking. Photovoltaics could be a big part of the solution for the nation, but not so great in Massachusetts. The resource we have is wind not sunshine

I didn’t know Baker floated the idea of a tax credit for remote workers. Great idea. But a worker can only work remotely if their boss lets them. Offering employers a tax credit to allow employees to conintue to work 100% remote might be a good idea too. There are so many places throughout Massachusetts that could benefit by the potential investment and revitalization that would bring, particularly the old industrial areas that were considered to be too “remote” prior to the necessity that COVID-19 created to literally work remote. A silver lining of this whole crisis imo. I’ve never been a fan of the Government’s longstanding push to empty the suburbs, and much of middle America in general, and to cram as much developement (and people) on top of each other and into the City as possible. We’re losing the livability character that Boston has always been so endeared for. We have too much development in Boston, that is too dense, too concrete and steel, not enough grenery and open space, and way too expensive for the average pocketbook, wheather individual or corporate. Encourage employers to continue the remote model that has begun during this crisis as much as possible. Get off Boston’s back, and give other areas a place to shine. That would be a win/win.

Also I would just like to mention that if you look at an environmental map based on emissions, the USA, Europe, Canada, and Austrailia are the Greenest, China is currently a major polluter, and much of Africa and Indonesia are even worse at the moment, as they continue to emerge. It’s always a good idea for us to look for ways for us to improve, but I think the concerns that many have, myself included, that we are going to “penalize” ourselves while other nations continue to pollute with impunity, is myopic, and ultimately, rather self-destructive. Such a pity that such an important consideration is completly missing from your “plan” Will.

Thank-you for all this information, Senator. Very informative!

The transition to renewables including hybrids and fully electric EVs is a positive, and I look forward to making the switch myself with my next vehicle purchase.

Current battery technology, however, leaves a lot to be desired in terms of energy density, maximum number of discharge cycles, recycling, and so on. Lithium, the main component of current current car batteries, is a dangerously reactive alkali metal. Serious incidents involving cars, skateboards, laptops and other technology items have occurred with devices spontaneously igniting. Manufacturers have gone to great lengths to provide triple layers of protection, but short-circuits can and do happen due to various technical issues such as lithium dendrites. There’s a lot of research being done in this area right now to cure those problems.

I’d like to see some research dollars go towards hydrogen power. Renewable [electric] energy sources can disassociate water into its constituents, hydrogen and oxygen. “Burning” that hydrogen in cars just “re-associates” the oxygen and hydrogen, producing water as its product (plus very, very tiny, trace amounts of nitrous oxide – much less than in current, carbon-based, internal combustion engines.) The two problems until now have been 1) how to economically produce all the electricity necessary to disassociate water, and, 2) how to safely store the hydrogen. Any clean electricity source, including wind, solar, tidal, and geothermal can be used to produce electricity. Many homes, businesses and even the Commonwealth (for example, along the Mass. Pike) now have solar arrays that generate clean electricity.

Pressurized storage tanks where the hydrogen has been absorbed by a metal such as powdered nickel, have shown to be very safe and extremely long-lasting, but heavy, so more research into other hydrogen-friendly materials is warranted. (Scientists are examining materials like powdered magnesium and forms of carbon such as nanotubes.) Hydrogen-fueled cars use exactly the same service infrastructure we already have in place because their engines are still internal-combustion engines, but much cleaner. So the infrastructure costs (e.g., auto service departments, gas stations converted to dispensing hydrogen) would be significantly lower to implement.

Iceland has been a leader in hydrogen technology; see, for example: https://fuelcellsworks.com/news/icelandic-new-energy-has-launched-2030-vision-for-hydrogen-in-iceland/. And Wikipedia has a fairly good explanation of splitting water: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_splitting

A hybrid hydrogen approach, fuel cells, still uses carbon-based fuels (but much less than current cars) in order to produce electricity. From what I gather, the main issue with fuel cells has been to maintain significant and steady electric production in a moving vehicle. By contrast, as I mentioned, safe hydrogen storage tanks would practically last forever, use no carbon-based fuels, produce almost zero pollution by-products, and are quieter than current engines.

It’s a great discussion topic and I look forward to whatever you, the legislature, and the new administration in Washington propose and enact into law going forward. Thanks again!

-Steve

Great article. I’m glad you mentioned the equity issues and the need to electrify buses and trucks. One comment – electrification lowers CO2 emissions, but it does not lower particulate matter pollution or microplastic pollution from tire wear, both of which negatively impact human health. Reducing VMT reduces CO2, particulate matter, and microplastic pollution.

You state that you “hope” EV sales will make up 25% of overall new vehicle sales between now and 2030. Since we’re only at about 1% now, we’ll need to get most of those sales on the back end of the timeline, meaning in 2026-2030 we’ll need more like 40%-50% of annual new sales to be EV to make up for low sales now. This would be a remarkable market shift over such a short time period, and frankly doesn’t seem feasible without significant federal and state intervention beyond current proposals. Even assuming Biden’s infrastructure plan passes, a big assumption, we’re orders of magnitude below target. You have put forward some high level ideas (rebates, manufacturer sales requirements) but when can we expect to see specific proposals to get us there, and when will legislation be put forward?

I would like to second and third all the calls for more dense and affordable housing near public transportation.

As someone who rents in a dense area and currently has a very small carbon footprint, I am ready to purchase a house, but due to the housing affordability crisis in the Greater Boston area, the economics are tilted in favor of moving to suburban sprawl, which will grow my carbon footprint greatly.

I would love to live in the city and bike everywhere, or take the train, with a minimal carbon footprint, but it is financially straining to do so. It is cheaper to move to the suburbs and maintain multiple cars and drive everywhere, and until we properly price carbon externalities and fix the housing crisis, people will continue to select or be forced into the “cheaper” option.

You can’t force people to live in cities. Especially now. Murder spiked by 55% in Boston last year. Especially with more people working from home and brick and mortar retail wiped out, the urban dream is dead.

I am not looking to force people to live in cities, but for making cities accessible and affordable, for those that choose to. City living has a much lower carbon footprint than suburban sprawl, and we need to incentivize it.

You are not going to be murdered stepping foot into a city. Boston is not a dangerous place.

Very smart analysis, Will. Thanks for taking the time to share your knowledge.

I wonder if the state could make some additional impact with a cash for clunkers program. We might also consider a subsidy for electric-powered lawn-mowers, chain-saws and snowblowers, coupled with a 25% tax on gas-powered versions of those items. That wouldn’t work without cooperation from our neighboring states, of course.

Thank you for this very informative post.

Regarding public transport, electric buses and electrifying all our commuter rail lines should be a priority. This will address health concerns and greenhouse emissions. I also think that buses should be free. The amount of money that is being spent on the new MBTA fare collection system is absurd, and generally, people riding the bus are less affluent.

State government is about to receive a lot of money, through the American Recovery Act and possibly through proposed infrastructure legislation. Using it to bring all our existing transit systems and equipment up to date should be the priority, as well as completing current expansions such as South Coast rail and the Green Line extension. I am skeptical of the need for high-speed rail to Springfield/Pittfield, and whether the benefits can justify the cost. Expanded, free bus service provided by the regional transit authorities can provide benefits quickly and be more easily adjusted to meet demand.

I agree that we should create a network of electric charging stations. Perhaps the state could offer incentives for property owners to add them, as it does for energy conservation improvements.

It is going to be a while before we know how the pandemic will affect commuting and work practices, so I think we should wait before initiating any new rail or subway expansions. Fix what we have first, and given planning and permitting requirements, it will have a more immediate benefit.

Any plan that completely disregards mass transit and human powered transportation is a complete waste of time in my opinion. This sounds like more of a love letter to the automobile industry rather than something that will actually make a difference. It’s time to give up our destructive addiction to cars.

Neither this post, nor EoEEAs plan “completely disregard mass transit and human powered transportation”. Both recognize the various positives of mass transit and human powered transportation. They just recognize that mass transit and human powered transportation do alone suffice to reduce emissions given our land use patterns.

I appreciate all the careful thought that has gone into this analysis. A couple of people have already mentioned e-bikes, and I’d like to endorse that – although they are only useful for relatively short distances, short hops are dirtier per mile than long trips, all else being equal. Bikes and e-bikes would also be more useful (in Boston at least) if the roads were in better condition.

As a manager I am being asked to think about new WFH policies, on the basis that WFH has finally been proven to be possible with little loss of productivity. I’m not sure that’s precisely true – what we’ve shown in the last year is that we can do it if we ABSOLUTELY have to – but I don’t think there’s much doubt that the number of WFH days per week will remain higher than in the “before times” for those who have the type of job that can accommodate it.

Thank you for your thoughtful analysis, Will. Another thing to consider is making it easier for people to access what they need from home or near home. One could create subsidized coworking hubs withhigh-speed internet and other amenities near peoples’ homes so they could easily work remotely and still have a little separation from infrastructure and relationship challenges at home. The hubs would provide a space to focus, they could be near schools or daycares to make it easy to pick up kids. They would offer companionship, collegiality and cross-fertilization of ideas. They could even have daycare and after-school programs, cafeterias and a range of social services or services for hire. If they are walking distance or near walking distance, or accessible within 15 minutes for most people, that wouod cut down a lot on transportation and emissions. These hubs could also be centered around public housing. You might have fresh fruit and veggie delivery days. There is so much we can do to multisolve challenges: greenhouse gas, transportation, lost productivity from commuting, social isolation, access to infornation/internet, health.

I have been watching the electric transportation scene since the beginning of this century, and am of the opinion that our failure to electrify passenger vehicles more quickly is partially due to the marketing and sales emphasis on BEVs at the expense of pushing more PHEVs. I believe this is a classic case of the perfect being the enemy of the good. Also there are higher profit margins for the manufacturers at the low level of penetration of EVs into passenger car sales.

Why do I think this? We have owned a PHEV (Ford CMAX Energi) since the beginning of 2013, and at this point have travelled over 60K miles and have a lifetime 86 mpg. We take short trips that often are within the all-electric range and occasional trips to NH that are not. And we almost exclusively charge at home with 110V. So ¾ of our miles travelled have been on electricity, and there are many others who might have similar driving requirements who would also benefit from never having to deal with concerns about their all-electric range, and have a fall-back to ICE/hybrid mode as needed.

Yes, 86 mpg is not net zero, but is is a lot better than the average passenger car mpg. So we can make a big dent right away in our goal to lower GHG from the transportation sector if we could only a) get manufacturers to push PHEVs as strongly as they push BEVs, and b) show some passenger car buyers that their driving requirements can be met with PHEVs.

PHEVs are a great option, almost as good as EVs for climate, and a better choice for many consumers today.

Thank you in particular for bringing up land use as a factor in this discussion. I took a look at the 2019 census commute mode share estimates, and they align with hypothesis that land use is possibly the biggest determinant of long term transportation emissions: in dense and walkable Cambridge, for example, only 27% of employed residents drove alone to work and 32% walked or biked. Some ways I would like to see Massachusetts improve its land use regulations to decrease emissions over the long term would be eliminating minimum parking regulations and permitting more dense development, particularly in already-dense urban/suburban areas and particularly near transit and jobs.

Continuing with the Cambridge example, I hope you’ll agree that there is vast room for improvement in creating a safe walking/cycling environment there; if so, I think it logically follows that much potential remains for their growth. Any car, even an electric one, uses a lot of energy, so cycling and walking disproportionately reduce emissions and therefore warrant investment, particularly in urban and suburban areas where their mode share ceiling is very high. Several intersections in Belmont, where I live and which has much untapped cycling potential, are terrifying to go through on foot or on a bike (Trapelo/White, Concord/Common, Lexington/Sycamore); they clearly serve as deterrents from choosing emissions-free transportation modes, so fixing them has a climate change impact as well as a safety one. The same could be said about other simple, pedestrian-friendly reforms, like making pedestrian signals automatically activate wherever possible.

The American Community Survey data indicate a 10% transit mode share in Massachusetts in 2019, so I’m a little unsure of where the 3% number cited in this post could be coming from or why it’s so different. I’d also like to voice support for a higher gas tax; ours is below the national average, which I find somewhat embarrassing considering the reality and urgency of the climate emergency and the fact that half the country doesn’t believe in it. Massachusetts has a lot more to lose from the possibility of worst-case-scenario sea level rise than from higher fossil fuel taxes.

3% passenger miles traveled vs 10% trip count is the most likely distinction.

Great information thank you Senator! I hope the tax incentive idea for employers to allow more employees to work from home is promoted again. Many employers never entertained the idea of allowing remote work until they were forced into it, and now many are realizing that it works quite well, so keeping them open to allowing remote working is important. Remote work isn’t an option for everyone of course, but for those who can and want to do it, it can be a huge improvement to the work/life balance, so much money can be saved on commuting expenses, and people could consider actually buying a house farther away, since there is no affordable housing or really affordable renting close to Boston, so not being tied to come into Boston for work would be a blessing for many.

Thanks for the thorough look at the issue. We want fewer care and fewer miles driven. And we need all miles driven to be in EVs. We are looking at it from the city perspective here in Cambridge – and finding the same summary: we must do more, we must be specific in goals by year if we are to reach our targets. AND the charging infrastructure has to be in place. AND the electric grid capacity has to be increased AND renewable. For EVs, installing chargers on public streets tapping off street lights is promising. We will be doing a pilot on that this year. Other cities have already proven it can work. And with street lights now being LEDs, there is some electric capacity already available on the streets where we need chargers. Available to those without driveways.

I’m not here to debate climate change. I’m not here to debate your methods of dealing with it. I am here once again begging you Senator to not inflict additional gas taxes and regulations on the middle class and poor of the state of Massachusetts at this time. We’ve just gone through a pandemic, Massachusetts has lost 30% of its small businesses, yes 30%. Only New York and New Jersey have lost more. Why can’t the legislature wait a year to let people get back on their feet before throwing more taxes and regulations at them? There seems to be no concern whatsoever for the people that this legislation is going to hit the hardest. Gas prices have already risen this year as much is $.75 per gallon and the TCI will automatically increase the gas tax every year without legislative approval or vote.

Before he resigned disgraced Climate Undersecretary, David

Ismay said it best “ “There is no bad guy left, at least in Massachusetts, to point the finger at, turn the screws on, and break their will so they stop emitting, That’s you, we have to break your will, right. I can’t even say that publicly.” Does anyone doubt the attitude he displayed is any different from the attitude of the legislature that voted for and wants to force these taxes and regulations down our throats at this time. Again, people in Massachusetts are suffering, this legislation can wait.

This is their plan…”The Great Reset”. Creative destruction I think they call it. They are going to reorder society in a completely dystopian way in which you have no more freedoms.

I agree with you, Joseph. The Legislature does not care until they run out of other people’s money. Gas taxes, millionaire’s tax – then graduated tax for all of us, etc. We have to feed the monster whether it is for Green Energy utopia or $5.55B in state retirement pensions. It will only get worse.

Now, getting out of here before they bleed us dry grows more tempting everyday.

good thread here. Notice how Will avoids weighing in. I share these concerns.

“So, we are hoping that more than one quarter of the sales over the coming decade will be electric.”

“The state already provides rebates up to $2500, but combined state and federal incentives could increase.”

A wealthy person getting a rebate for a second car often sitting unused in a driveway and a low-income person getting a rebate for an electric car that will be driven many miles as part of an uber/lyft/taxi system should not be treated as anywhere near equivalent. Rather than fraction of sales, can some other measures be devised and incentives designed accordingly?

Priority should be given to ensuring publicly owned, frequently driven vehicles like police cars and buses are electric and privately owned cars that are necessarily driven many miles, particularly in ways that reduce overall car ownership… There should be more attention to the emissions caused during car manufacture even if they don’t occur locally, with focus on accelerating shared use of fewer vehicles. The state should cooperate closely with those developing autonomous shared-use vehicles to ensure that they are electric and that the Comonwealth is hospitable… recognizing that autonomous vehicles may be viable much sooner on highways that in crowded neighborhoods with complex intersections and driver/pedestrian behavior.

Particularly given a full life cycle analysis, and a focus on social justice, subsidy systems should support use of high gas mileage hybrids as well as pure electric vehicles that are less viable for those who don’t own a driveway. With gasoline taxes used to pay for subsidies.

And there should be more focus on improving the most polluting portion of fleets, and the average performance, relative to just improving the least polluting portion. So, raising fuel efficiency standards makes far more sense than subsidizing purchase of electric cars without raising such standards.

And, as others have commented, encouraging/subsidizing use of bicycles and e-bikes as an alternative to automobile use should be a major focus.

Thanks for all your good work on this and other issues.

Your analysis makes a lot of sense to me, and I don’t have a lot to add. One blue-sky thought that might be worthwhile including in a “supporting research/technology” section of the work the state is doing: If we could find a way of closing the carbon cycle (i.e. synthesizing gasoline from carbon dioxide) without losing *too* much energy going all the way around the cycle, that would allow gasoline to act as a storage mechanism for renewable power and massively reduce the infrastructure change required to get to zero carbon (because we wouldn’t need to substantially reduce gasoline-miles traveled). The technology isn’t there yet, but it is actively being worked on, and if the state has ways to encourage this type of research, it might be an outside bet worth putting some money into.

The following comments apply to more than transportation since they reflect a common concern and objective of “electrifying” activities and processes in order to reduce the amount of harmful emissions they generate because electricity as a source of power is “clean” and will become “cleaner” as a growing proportion is generated by renewable, non-polluting sources (solar panels, wind power, hydroelectric…). Two challenges for this happy scenario are how to ensure that (1) The increased capacity needed (I have seen quotes of a two to threefold increase being required) to achieve electrification will be available, and (2) This capacity will be reliably available to satisfy peak demands when a large proportion is supplied by renewable sources (especially wind and solar) that fluctuate substantially in their capacity as a function of weather conditions and time of day. Periods when the capacity of renewables serving an area is low may/will coincide with periods when demand is at a peak.

With respect to (1) for example reportedly the amount of land required to accommodate all the solar panels needed to contribute the capacity needed from it is unrealistically large given other critical uses of land, such as for agriculture. Here is a link to a 2015 report on the capabilities and limitations of Wind Power from the US Department of Energy (i.e. written before it may have been corrupted by the anti-science, “alternative facts” ethos of the Trump Presidency) – https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/WindVision_Report_final.pdf

There are several approaches (not mutually exclusive) to smoothing out the electric power supply to an area. One is to retain a significant proportion of total capacity in the form of base load sources whose capacity is not inherently dependent on weather conditions (except in Texas where they did not bother to invest in weatherizing vulnerable elements of the overall system). Assuming coal and oil and fossil gas-fueled power plans are unacceptable then the alternative source of baseload power is nuclear. I personally support including nuclear power as an element in the long term solution, but I realize that others have very different opinions. Politically this may be unacceptable as it is proving to be in Japan and Germany and elsewhere following horrendous mishaps (Chernobyl, Fukushima, and much less horrifying Three Mile Island).

Other approaches to smoothing out the capacity of available electric power include (a) Building robust wide area transmission systems so a surplus of capacity in one area with favorable weather conditions can be sent to another area with a shortage because of unfavorable weather conditions on the basis that these conditions can vary widely across the coverage area of this transmission network, and (b) Establishing storage capacity from which power generated during periods of surplus supply can be drawn when demand exceeds current supply.

Here is a link to a recent report advocating approach (a) and describing what needs to be done – https://cleanenergygrid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ACEG_Planning-for-the-Future1.pdf

Approach (b) encompasses several approaches, including battery storage (the future of batteries alone raises a host of complex issues, including the dirty secret of today’s most common lithium-ion batteries (used in everything from smartphones to electric cars), which contain large amounts of metals and materials (notably cobalt, high purity nickel and graphite) that cause significant pollution and increase CO2 emissions during the mining and refining process. These batteries are also known for exploding and causing fires. Hope for the future lies with solid-state batteries that instead of the flammable liquid solution in Li-ion batteries replace it with thin layer solid electrolytes. Advocates point to their potential for much higher energy densities – beyond 1,000 watt hours/liter (Wh/L) for an automobile range of 500 miles – and the ability to handle more charging cycles to reach the holy grail for vehicles of a 1 million mile battery.

Other possibilities for storing surplus energy produced by renewable sources during hours of slack demand and delivering it pollution-free when needed include pumping water up to reservoirs that can then be released to generate hydroelectric power and powering electrolysis machines to make hydrogen, eventually providing a store of carbon-free energy for dispatch when demand is strongest.

However, producing hydrogen, storing it and using it to generate electricity, a process known as “power-to-gas-to-power”, is inefficient and expensive. Energy is lost both in breaking the molecular bond between hydrogen and oxygen in water and in burning the resulting hydrogen in turbines. So hydrogen is perhaps a longer term solution.

Bottom Line – Somehow we have to take a holistic end-to-end multidisciplinary approach if we are to tackle successfully the human activities which contribute to Global Warming. We must overcome the obstacles in the way of Federal Action (I will not even touch the need for cooperation at the global level) working in conjunction with states and local authorities (despite our dysfunctional political institutions and the immoral (or is it amoral?) behavior manifested by many influential policy makers (or policy breakers) and leaders in the private sector who see and act beyond shareholder (and personal) financial value maximization as their sole lodestar. As Ben Franklin might put it were he alive today, “We must undo the damage to our habitat together or surely we will be undone separately.”

Where is all the electrical power coming from to charge these EV’s and run the heat pumps (which are notoriously inefficient at single digit temperatures)? Nobody wants to be near a nuclear plant and solar panels and windmills don’t cut it during a snowstorm – just ask the people in Texas. Meanwhile the “northern pass” power line to bring down green hydro power from Canada is still in being fought by nimbys who don’t want it spoiling their view. Until there’s a way to get reliable power into the grid this is all an expensive pipe dream.

Re: your added thoughts re: Autonomous, Connected Electric Shared (ACES) vehicles

“ACES vehicles will likely play the biggest roles in dense areas — that is certainly the pattern with Uber and Lyft today.”

True, but I suspect that will be rather less true for ACES vehicles than it is for Uber/Lyft. It can be unpredictably difficult to locate a willing driver in less dense areas, and it may at some point become significantly easier to schedule a driverless vehicle in such locations. Plus, it is plausible that, in the early stages of autonomy, Uber/Lyft drivers will ferry folks to spots near highways where they will be able to transfer into multi-passenger autonomous vehicles that will trek back and forth long distances on highways considerably less expensively per rider than is now the case for single passenger trips with hired drivers. Particularly if the state sensibly plans to facilitate such possibilities.

“Single occupancy shared vehicles do not necessarily reduce VMT: Uber and Lyft have been perceived as increasing congestion unless occupied by more than one person at a time.”

Indeed. And it’s hard to estimate to what degree Uber/Lyft passengers would otherwise own vehicles vs. use public transportation. Alongside VMT we surely should consider numbers of vehicles manufactured, particularly given the often horrifying impacts of battery manufacturing process, see e.g., https://unctad.org/news/developing-countries-pay-environmental-cost-electric-car-batteries

I see a study in Austin, TX found:

“This university study revealed that the availability of ride sharing has a drastic impact on commuters’ behavior when it comes to alternative transportation options other than ride sharing. Significantly, the study found that during the roughly one-year stretch when Uber and Lyft were banned in the city, 41 percent of commuters used their own vehicles to fill the void, while 9 percent purchased a car to handle their transportation needs. More significantly, only 3 percent of commuters opted to use public transportation in the absence of ride sharing services.”

https://www.foley.com/en/insights/publications/2018/02/ride-sharing-is-already-reducing-car-ownership-and

But presumably those ratios would vary greatly from one city to another, depending particularly on the quality of available public transportation services.

Allow me to add that, according to the pro-Green, not-even-close to the center, Environmental Social Justice folks, these are their calculated costs to own and operate an EV:

Purchase: $40,000 (avg)

Tax Credits: $0

Charging Station: $1950 (avg)

Charging: $79.20 (Rounded up to $2.64/day charge for 30 days)

Insurance: $4,500

TOTAL: $46,529.20

They go on to state that this would be “nearly impossible for the average middle-class household to pay”. See how this may work in MA with one of the highest costs Kw/hr. @ 22.32. Same goes for RI.