This post is a technical note — a building block toward more substantive posts. It reviews studies based on census data that compare affordable housing stock to households by income level.

Measurement challenges

Defining affordability

What housing is “affordable?” A common standard for “affordable” housing is housing that costs not more than 30% of income. This definition is embedded in many housing regulations, notably those governing the federal low income housing tax credit. However, 30% of income means very different things at different income levels and for different household types and circumstances. The lowest income households have income barely sufficient to cover necessities other than shelter, and they may not be able to afford to pay 30% of their income as rent. Conversely, at higher income levels, even after spending well over 30% of income on housing, a household may still have income sufficient to cover all other needs and many wants. Additionally, housing costs trade off against transportation costs — the savings associated with living close to work may make a high housing cost more tolerable. Finally, different kinds of households face different mixes of necessities — for example, families with young children may face child care costs and households with health issues may face higher health care costs.

The issues in measuring non-housing needs are so complicated that most studies of housing markets settle for using the 30% housing standard (implying 70% for non-housing needs). The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard recently did a study comparing the the 30% standard to a more complex effort to measure the costs of non-housing necessities. The gist of the study is that the 30% standard is a rough and ready comparison tool, but probably overstates the ability of low-income households to pay for housing and understates the ability of higher income households to do so. The 30% standard also tends to overstate the ability of families with children to pay for housing.

In the end, the fact that the 30-percent standard provides a reasonably accurate measure of the share of households for whom housing costs are creating a financial hardship, coupled with the simplicity of its calculation and its ready availability over time and for broad geographic areas, supports its continued use as the go-to benchmark for assessing the overall extent of housing affordability problems. But because of its imprecision at the household level, it is important that it not be the only data point used when crafting policy responses that target specific segments of the renter population in different market contexts. The large share of income required for non-housing expenditures by the lowest-income households also points to the need for more sensitivity in policies setting the share of tenant income required to be spent on rent. The analysis presented here finds that for the lowest-income households, this share may well need to be less than 30 percent to avoid financial hardship given the large share of income needed to pay for other necessities.

Affordability is, of course, a matter of degree and it is common to consider multiple percentages of income, for example, referring to households spending over 30% of their income on housing as “cost burdened” and households spending over 50% as “severely cost burdened.” To apply these constructs, we need to measure both income and housing costs.

Measuring income

The primary source of recent regional income data is the American Community Survey (“ACS”). HUD regulatory constructs like “Area Median Income” are built up with various adjustments from ACS.

The income section of the ACS survey form includes questions only about money sources of income. The ACS does not inquire as to whether or not a household benefits from a housing subsidy and it only asks yes or no questions as to whether food stamps or health care subsidies are received by household members. The Census does produce several other income data products, but none of them allow a complete analysis of household economics, especially at the state or metropolitan level that is of interest to us.

- The Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement is designed to identify national economic trends and focuses on money income.

- The Survey of Income and Program Participation is used for deeper longitudinal research, primarily from a national perspective. It collects much richer household economic data, including program participation data, but does not capture the size of rent subsidies, although it captures subsidy receipt as a yes or no variable. Its sample size is smaller than the ACS sample and data is not published for geographies below the state level.

- Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program is based on ACS data but also integrates administrative data like IRS data to provide small area (e.g. school district) estimates of poverty and income that are useful for allocation of federal funds. It does not support more refined economic analysis of households.

The limitation of survey data to money income creates two kinds of assessment challenges: (1) It makes it hard to compare economic need across low and moderate income populations since program participation may be higher among the lower income population; (2) for housing subsidy programs which are not entitlements, but are limited by availability, it makes it harder to evaluate the extent that needs are being met.

A logistical challenge in using the ACS income data is that ACS tabulations focus on either absolute income amounts or comparisons to poverty levels: Although ACS data are fundamental to HUD income threshold definitions, the ACS does not routinely tabulate the population of households with respect to HUD income levels. Counts of households meeting HUD AMI thresholds have to be derived by special tabulations. Except when done by researchers with special access levels, this requires use of the Public Use Microdata Sample files in which location is partially obscured to protect confidentiality – one needs to cross walk Public Use Microdata Areas to HUD market areas and this may, in some instances, involve an additional layer of estimating where the boundaries do not line up. See Appendix A to Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Report 19-1, The Growing Shortage of Affordable Housing for the Extremely Low Income in Massachusetts. A useful tool for allocating PUMAs to market areas is the Missouri Census Data Center’s Geocorr 2022 Geographic Correspondence Engine (used by the NLIHC analysis discussed below).

Measuring rent

The ACS is again the primary source for household rent payment data, and the only source in which rent levels can be cross-tabulated with income levels. However, there is an important ambiguity in the ACS rent data for low-income households. The survey form asks: “What is the monthly rent for this house, apartment, or mobile home?” If rent is subsidized, it appears that some respondents answer this question with the amount they themselves pay, while others answer with the total rent including the government subsidy. A careful comparison of rent responses with HUD administrative data found that while most households in public housing or project-based section 8 housing reported a rent close to the payments they made themselves, tenants with mobile vouchers were split, with 61% reporting a rent amount closer to the unsubsidized contract rent than to their own payment and 46% reporting a rent within $50 of the unsubsidized contract rent. The report concluded as follows:

The majority of HUD housing assistance recipients examined in the present analysis report ACS rents that are clearly below market rents, either by omitting the subsidy they receive from HUD or, as in the case of conventional Public Housing, because they are assessed a payment in a context where market rent does not apply. . . . Based on the findings of this analysis, including ACS self-reported rents for households receiving HUD rent subsidies would downwardly bias an estimate aiming to represent ordinary residential rent. In calculating such estimates, it would be better to exclude the majority, if not all, recipients of HUD assistance.

What are Housing Assistance Support Recipients Reporting as Rent? SEHSD Working Paper 2017-44, W. Ward Kingkade

Unfortunately, since the ACS does not track receipt of housing assistance, it does not allow exclusion of households receiving rent subsidies from estimates of rent. This means that, especially at the lower end of the rent range, reported ACS rent will be down-biased below market reality by housing subsidies. This does not necessarily affect HUD estimates of Fair Market Rent: These estimates are based on the 40th percentile rent — most of the apartments for which rent is down-biased are likely to be below the 40th percentile anyway. But it does mean that since some but not all low income people benefit from housing subsidies, the low-end rents in the ACS are a blend of market and subsidized rents and so understate the rents paid by those low income households who do not receive housing subsidies. To assess the rents paid by those low-income households who do not receive housing subsidies it is necessary to back out the households who do — either (a) by matching program administrative data by household (hard to do across the full range of federal, state, and local programs) or (b) by assuming that the lowest rent households as appearing in the ACS are all receiving housing support and backing out an estimated share of them using aggregate data about the stock of affordable housing and the availability of vouchers. See the Urban Institute report discussed below at page 19 for an example of this approach.

The Boston Foundation’s 2022 Housing Report Card highlights the much higher rents showing in Zillo data than the American Community Survey. Zillo data about the range of rents in the market could confirm whether it is reasonable to treat the low range of the of the ACS rent data as consisting primarily of subsidized households.

Alternative comparisons of rent to income

Given constructs of “affordability” as rent (or ownership-costs) compared to income and given measurements of income and rent, one still has a choice about how to frame the data. There are two common metrics:

- The rates at which people at given income levels are rent burdened — i.e., have rent above 30% (or are severely burdened, over 50%).

- The extent to which homes are available and affordable to people at given income levels (where a home is available and affordable to a person at that level if it is vacant or occupied by a person at or below the level and meets the rent affordability percentage at that level).

The second metric makes a statement about the balance of supply and demand for homes at a given income level, while the first metric makes a statement about the economic pressure that households are feeling as a result of that balance.

Some study results

National Low Income Housing Coalition

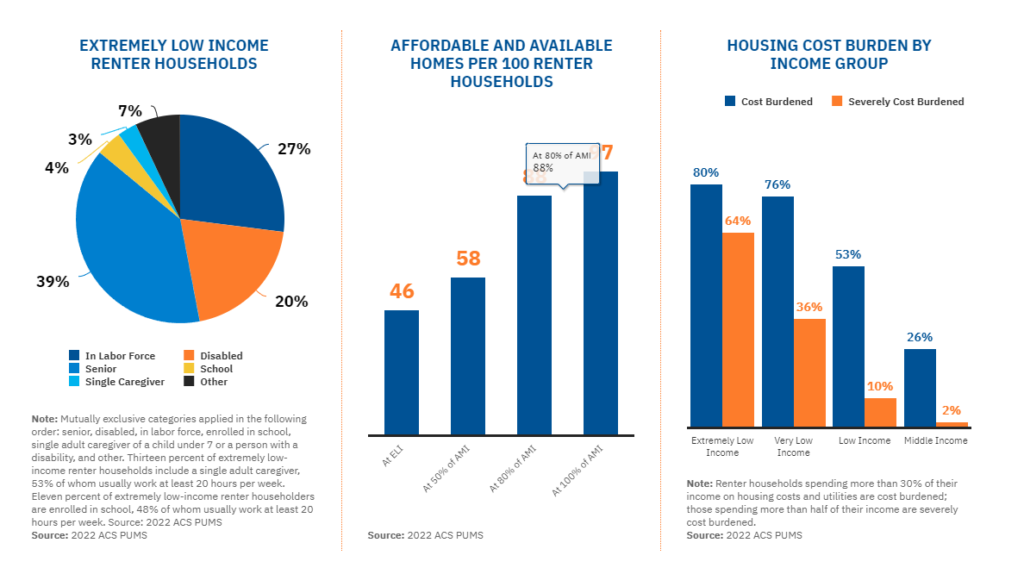

The National Low Income Housing Coalition is an advocacy network devoted to supporting federal investment in low income housing. They annually produce a gap study focused on housing available to the population at the extremely low income level (“ELIL”), defined as under 30% AMI or the poverty line, whichever is higher. In Massachusetts, that selection will equal those below the 30% AMI level (except in the largest households). The report makes the argument that federal resources should be focused on developing housing for ELIL households because they are the most cost burdened and because they face the lowest rate of affordable and available homes. It further points out that most of the ELIL population is either senior, disabled, or working. Below appears a screen snap from the gap report’s analysis of Massachusetts households.

In this analysis of 2022 ACS data, 316,201 renter households show as Extremely Low Income, of which 170,810 (54%) are renting homes that are not affordable at the 30% AMI level (i.e., in which rent exceeds 30% of the 30% AMI level). Note that a large portion of ELI households have incomes far below the ELIL level.

Based on the acute need in the ELIL population, the report argues against deploying resources to assist middle income renters:

Federal housing subsidies designed specifically to serve middle-income renters are a misguided use of scarce resources to address affordability challenges that, nationally, are relatively small in scale and can be addressed with local solutions.

The Gap: A shortage of Affordable Rental Homes, p.21

Since the analysis relies entirely on ACS data, it suffers from the limitation that it doesn’t reflect the availability of housing subsidies for different populations as discussed above. This has two consequences:

- For the portion of ELIL households that are holding mobile vouchers the rent burden may be overstated since a majority in that group are reporting the contract rent, not their own payments.

- To the extent some subsidized units are reserved for ELI households, the supply available to VLI and LI is overstated. The premise of the analysis is that units affordable and available to the ELI population are also affordable and available to the VLI and LI populations and this may not be true for units operating under program rules.

Other data sources could be used to correct for these limitations of the ACS data. The resulting comparison would likely show a somewhat less dramatic contrast between the ELI and VLI/LI groups.

The gap analysis highlights differences between Massachusetts and the rest of the nation. Massachusetts offers somewhat more affordable supply for extremely low income households with the result that they are somewhat less rent-burdened than elsewhere. At the same time, lower and moderate income homes are roughly equally burdened. The table below extracts this comparison from the report:

| >50% Rent Burdened MA | >50% Rent Burdened US | Affordable/ Available Rental per 100 MA | Affordable/ Available Rental per 100 US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELI | 64% | 74% | 46 | 34 |

| 50% AMI or Less | 36% | 35% | 58 | 56 |

| 80% AMI or Less | 10% | 9% | 88 | 89 |

| 100% AMI or Less | 2% | 3% | 97 | 98 |

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

In 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston conducted a study similar in approach to the National Low Income Housing Coalition study, also using the ACS data (from 2016). The Federal Reserve Bank focuses on Massachusetts only and it dives deeper in the following respects:

- City and town level data;

- Projections for expiring affordability restrictions;

- Adjustment of ELI population to exclude transient ELI groups like students.

As to the basic statistics, the results are similar to the NLIHC report:

- 274,842 ELI renter households in 2016, while NLIHC found 316,201 in 2022. The Fed report excluded students from the ELI category; adjusting them back in (using the percentages at footnote 7 and associated text) brings the Fed count to 304,289 very close to the NLIHC count.

- 58% of the ELI population was extremely cost burdened as opposed to 64% in the NLIHC data. The student exclusion account likely tends to lower this statistic.

- 48.6 Affordable/Available units per 100 ELI renter households as compared to 46 in the NLIHC data.

The Fed report (at page 15) makes a point that aligns with NLIHC’s analysis of the cause of scarcity of affordable units: “34 percent of ELI-affordable units were occupied by households with higher incomes, thus making them unavailable. If other income groups were not occupying affordable and otherwise available units, the total number of AA units would have been close to 75 per 100 ELI households . . ..”

The Fed report attempts a useful analysis based on administrative data of how much of the housing that is affordable for ELI households comes from different public program sources. This analysis is incomplete due to its overreliance on the National Housing and Preservation Database for the number of state-subsidized units. The NHPD is primarily focused on identifying properties whose federal affordability requirements are expiring. It does not cover many state subsidized affordable units. Appendix B of the report acknowledges the incompleteness of the NHPD as to state-subsidized units, but the report does not adduce additional sources for state subsidized units. Massachusetts is unique in having its own state funded public housing system and these units are apparently omitted from the Fed analysis. The Fed analysis comes up with 3.4 state-subsidized units per 100 ELI households, which works out to approximately 10,000 units. However, state funded public housing is 43,000 units, a large share of which are occupied by ELI households, and there are additional private affordable units that the state subsidizes with state funds or with a combination of state and federal funds.

Urban Institute

The Urban Institute prepared an earlier analysis of the ELI affordability based on American Community data: The Housing Affordability Gap for Extremely Low-Income Renters in 2014. The analysis makes findings similar to the later reports and, for us, is most noteworthy for its helpful methodological explanation, especially its assumption about the reporting of rent in subsidized households:

[U]nits with project-based rental assistance, including public housing, project-based Section 8, Moderate Rehabilitation, other multifamily units, and USDA, report an affordable gross rent in the ACS, and are thus subtracted from the naturally affordable count.

The Housing Affordability Gap for Extremely Low-Income Renters in 2014,

Boston Foundation Report Card 2022

The Boston Foundation’s 2022 Housing Report Card shines a helpful spotlight on affordability issues and trends, but does so using broader categories — not differentiating by HUD income levels. The findings include that income growth has not kept up with rent costs for lower-income renters, and lower-income renters are increasingly burdened.