In an effort to gain insight as to how the COVID-19 pandemic could impact public transportation demand going forward, I examined public transit ridership in the wake of the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Acutely aware of the many differences between 1918 and today, I set it out to determine whether I could learn anything useful by looking at ridership data from that period.

The 1918 Flu

The 1918 Flu Pandemic had 3 rapid re-occurrences over 9 months in 1918 and 1919 before settling into a pattern of seasonal re-occurrence.1 In Boston, influenza hit in the fall of 1918.2 Schools and amusements were closed for 4 weeks in October of 1918.3

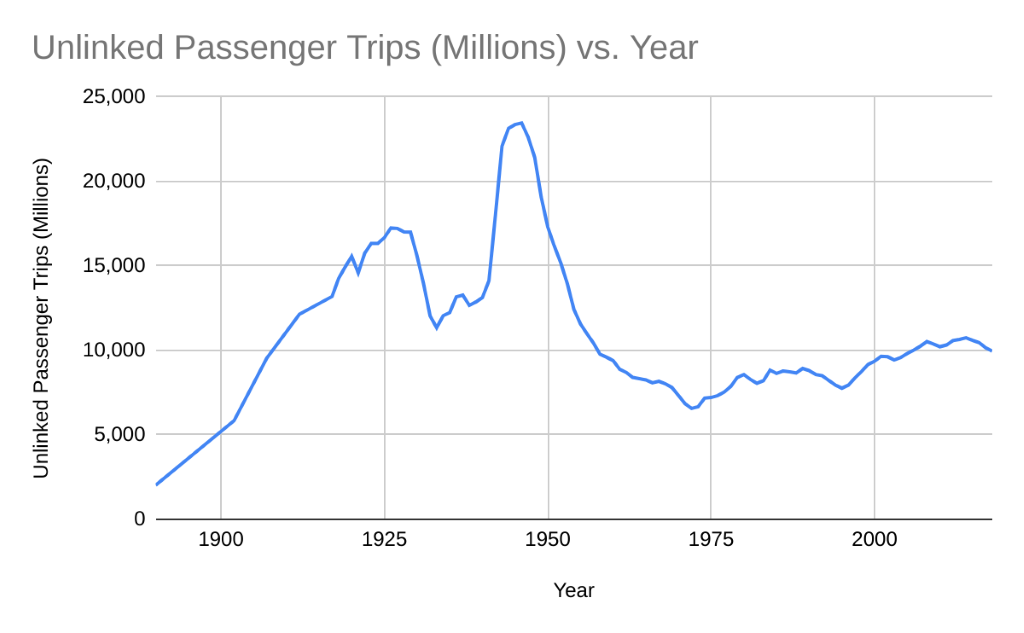

National Transit Ridership

The American Public Transportation Association’s Public Transportation Fact Book – Appendix A: Historical Tables4 are a great source for national information about historic public transportation ridership. That data set includes in Table 121: All Modes Total Statistics “All Modes Unlinked Passenger Trips,” which is the raw number of transit trips in the United States. While this tally does not control for population growth, or system expansion, it does give us some insight into public behavior in the years immediately around the 1918 flu. It does not appear that concerns about influenza led to a decline in transit ridership. In fact, 1918 saw a raw increase in ridership over 1917, albeit at a slightly slower rate than previous years.

Ridership growth continued until the Great Depression, when it declined sharply from 1929 to 1930 and then stayed relatively flat through WWII. There was an increase in ridership through the mid to late 1940s, but then transit declined substantially in the post-war period and bottomed out in the early 1970s.

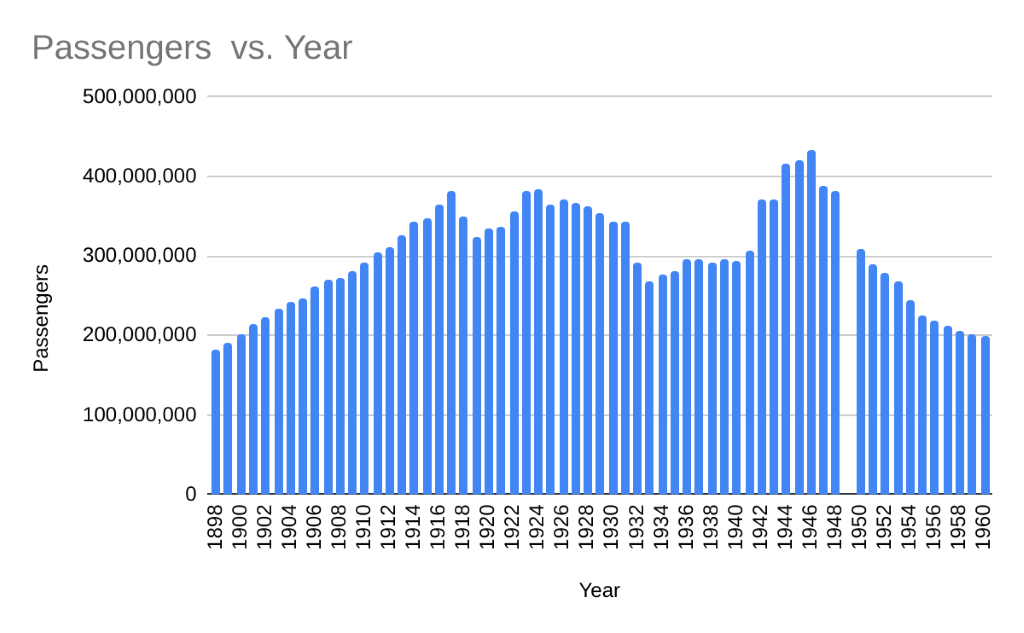

Boston Ridership

Ridership information from the Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) and its successors provide an interesting local snapshot of trends from the era. I assembled a table of total revenue passengers for the years 1898-1960 by examining the Annual Reports of the BERy and its successor the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA.) I was able to find these documents in electronic form on the State Library’s website. At a glance, ridership numbers would seem to support the theory that the pandemic caused a dip in ridership.

1918 saw a decline from the high of 381,017,338 revenue passengers in 1917 to 348,664,700 revenue passengers, and a further decline in 1919 to 324,758,685 revenue passengers. However, after review of the annual reports, there is another likely cause of this decline in ridership: transit fares doubled over the course of two years.

In 1918, the legislature passed the “Public Control Act.”6 Prior to July 1, 1918, the railway was operated by the stockholders, but from that date on, the railway was operated by trustees appointed by the Governor.7 The law “…expressly imposed upon the trustees two distinct duties. The first was that of establishing the service upon a self-supporting basis… The second duty imposed upon the trustees was that of bringing the railway to a condition suitable for efficient operation.”8 In order to meet its duty to establish self-supporting service, the trustees raised fares from 5 cents to 7 cents effective August 1, 1918.9 The increased fare was deemed to be insufficient to cover costs, and an 8 cent fare went into effect on December 1, 1918.10 With service still running at a deficit, the fare was increased to 10 cents effective July 10, 1919.11 This doubling of fares brought the railroad into the black but it did so at the cost of ridership.

The first increase from 5 cents to 7 cents coincided with the arrival of the flu pandemic in Boston in the fall of 1918. The annual report for 1918 only briefly mentions the pandemic:

During part of the period in which the seven-cent fare was in effect the business of the company was seriously affected by the epidemic of influenza, which reached Boston in September. This necessitated the closing of schools and places of amusement for nearly four weeks with the result that the earnings in October, 1918, under a seven-cent fare, were less than fifty thousand dollars in excess of the earnings of October, 1917, under a five-cent fare.

There is no further mention of the pandemic in any other annual report.

The same report also contains a month to month comparison of ridership from 1917 to 1918 while 7 cent fare was in effect:

Per Cent, of Decrease

August 1918 11.49%

September 1918 20.02

October 1918 26.48

November 1918 13.64

4 Months 1918 17.88%

While it is difficult to untangle the impact of influenza from the impact of fare increases, I believe that the limited discussion of influenza in the annual reports indicates that the impact on ridership was limited. I believe that the proximate cause of the ridership decline the substantial increase in the cost of service. The 1920 annual report states “It was inevitable that higher fares, though increasing revenue, would cut down on riding. The record verifies this expectation…” One interesting observation from that report is even at that early date, automobiles were already in competing for transit passengers:

“It will be noted that while there were between ten and eleven million more passengers carried in 1920 than in 1919, there were 600,000 fewer passengers carried upon Saturdays, Sundays and holidays. The explanation is that upon the days last named the automobile is in more general use as a substitute for the street car. Even upon the days of ordinary business no one observing the multitude of automobiles that choke the streets leading to the business center of Boston in the morning and at night can fail to appreciate the serious nature of the competition between that form of transportation and the street railway.”13

Overall, the ridership patterns of the BERy and the MTA loosely reflect the APTA All Modes Total Statistics: strong performance in the 1910s and 1920s, followed by a dip during the Great Depression, ridership peaks in the 1940s and then long-term sustained declines caused by competition from automobiles.

Conclusion

I think it is difficult to draw any meaningful conclusions from the transit ridership response to the 1918 Flu Pandemic. In Boston, the fare increases muddy the waters too much. While it appears as though the pandemic did not have a sustained impact on ridership, the way we live and technology have changed too much to make 1918 a perfect parable for the COVID-19 pandemic. Our knowledge of virology and public health has increased substantially. Widespread automobile use has changed settlement patterns, resulting in a massive suburban sprawl. Perhaps most significantly, information technology will allow many professionals to work remotely with little to no loss of productivity.

Many of the issues that operators were grappling with in the early 1900s are still issues today: governance, revenue, fares and state of good repair. While I was unable to draw any strong conclusion about the ridership response to the pandemic, it was still an interesting exercise to read the historic annual reports.

Thank you for this worthy history lesson.

Thanks, I think this provides some important historical context even if the conclusion is ultimately ¯\_(?)_/¯. I think one key difference that we do have to keep in mind is that today remote work is an option, and that it’s likely that the number of people taking that option (even if only a day or two a week) will increase even after the pandemic subsides. And what that means is that traditional downtown-oriented rush hour commuting is likely to decline a bit relative to off peak ridership, which is actually a good thing for transit’s efficiency.

I just finished reading Barry’s “The Great Influenza,” and he specifically notes the paucity of references to the 1918 influenza in literature and public documents. One reason it was so poorly reported is that anything that “lowered morale” during WWI was considered treasonous and was punishable. I don’t think we can rely on lack of reference in annual reports as an indicator that it had limited impact on ridership. Of course, the question not able to be addressed is the impact of ridership on spread of the virus.

Very interesting point!

One aspect of the switch to public ownership concerned fare increases. People considered the increases “unfair” then as they do today. Politicians were wary then of raising fares for public. Nowadays rather than raising tolls on public roads, the reverse happens: those who use public face fare increases that far outstrip those for highways and fuel.

This is an interesting way to learn some local history–thank you Andrew (and Will)! I agree with the strong caution in drawing too many direct comparisons between then and now, although thinking about what is similar or different offers great food for thought! Shout out to Arcady for the clever stick figure in that comment!

Thank you, Andrew, this is really interesting, and your measured conclusion seems warranted. But as a history and data wonk, I love this analysis (I taught the required history of urban policy and planning at Tufts Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Department for many years). And seeing the charts for the longer time period. And I also remember John Barry’s point brought up by Kris above about how little a literature footpring the 1918 pandemic left despite its traumatic impact on Americans at the time. Besides the “patriotic” regulations against spreading alarm about the flu, Barry argues that people just wanted to forget and move on. The worst affected were healthy young people in their teens and 20s, and in particular the masses of young men being called up for WW1). Older people were not so badly impacted. Which I guess could be another reason transit didn’t see a big decrease?