On September 14, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) released a report detailing preliminary strategies for rebounding from the financial strain the system has faced in the wake of low ridership associated with COVID-19.

Six months in, the pandemic has fundamentally changed the ways we think about and engage with most aspects of daily life, including our use of public transportation systems. At the onset of the outbreak, our office began examining trends developing in hard-hit cities across the globe to better understand the issues we’d soon face in Massachusetts, and how we might work to respond. This post explores ridership trends and agency responses across several cities in the US and abroad, and details the evolving local outlook.

For additional historical context, please refer to a post authored by the Senator’s chief of staff, which probes ridership during the 1918 flu pandemic.

A Changing Landscape

Before COVID-19 forced strict lockdowns in Italy, approximately 55% of residents in Milan utilized some form of public transit on a daily basis, accounting for an average of 1.4 million daily trips. After an extended system-wide shutdown, the metro reopened on May 4 at reduced service levels, accommodating a maximum daily ridership of 400,000, while promoting social distancing protocols and employing strategies to ease overcrowding, including staggered station closures.

Similar scenarios played out in cities across Europe and the UK before reaching our shores. Stay-at-home orders diminished demand and service levels, while the goal of flattening peaks in public transit use to lessen transmission forced a reorganization of public life, encouraging the use of alternative modes of transportation.

As lockdowns lifted, transit authorities introduced phased reopening plans focused on managing ridership density and commuting demand, and instituting high-visibility disinfecting and protective measures, while grappling with rider reluctance to return to systems widely considered unsafe. According to a June poll, 70% of Londoners no longer felt comfortable with the idea of commuting to work via public transit. Although fears of public transit systems as “super spreader” environments were not ultimately supported by public health data, ridership levels have struggled to rebound in Western countries. Cities that have experienced the most success in returning to mass public transit – such as Hong Kong, Seoul and Tokyo – have adopted aggressive testing and contact tracing programs, buoyed by longstanding cultural traditions of wearing face coverings in public.

In the US, San Francisco’s BART system experienced a 94% drop in ridership in April, while September data suggests the system is still operating at 89% below pre-pandemic baseline levels.

In Washington DC, the WMATA has had rail and bus ridership drop as much as 96% and 82%, respectively; the system’s general manager, Paul Wiedefield does not expect full service to return until at least spring 2021.

Chicago’s CTA has maintained normal service levels on five of its eight rail lines despite experiencing an 82% decrease in ridership. New York’s MTA, by contrast, has been running on an “Essential Service Plan,” which has preserved most peak-time service while eliminating some weekday service after experiencing an 87% drop in rail ridership and 60% drop in bus ridership.

The MBTA

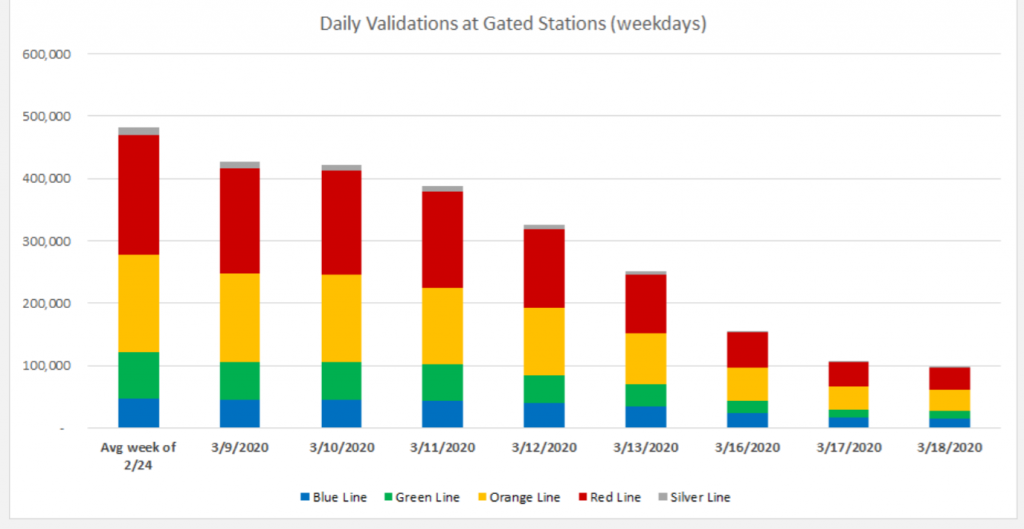

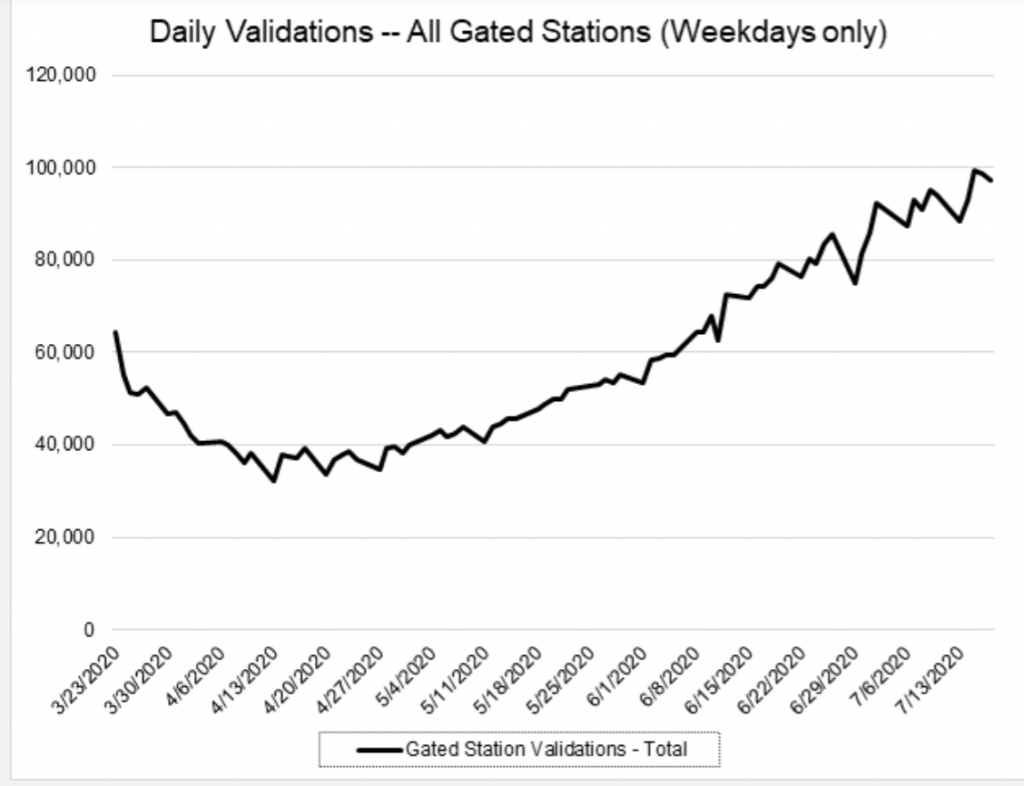

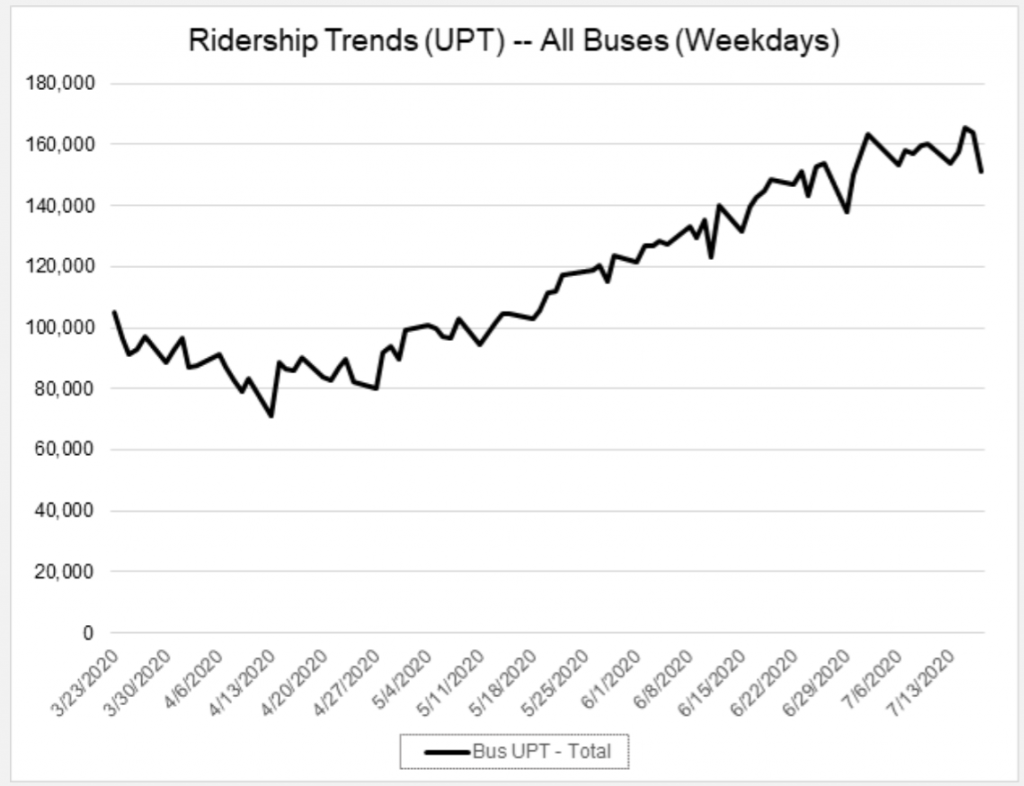

Following Governor Baker’s state of emergency declaration on March 10 and closure of all non-essential businesses on March 23, the MBTA experienced an immediate system-wide drop-off in ridership:

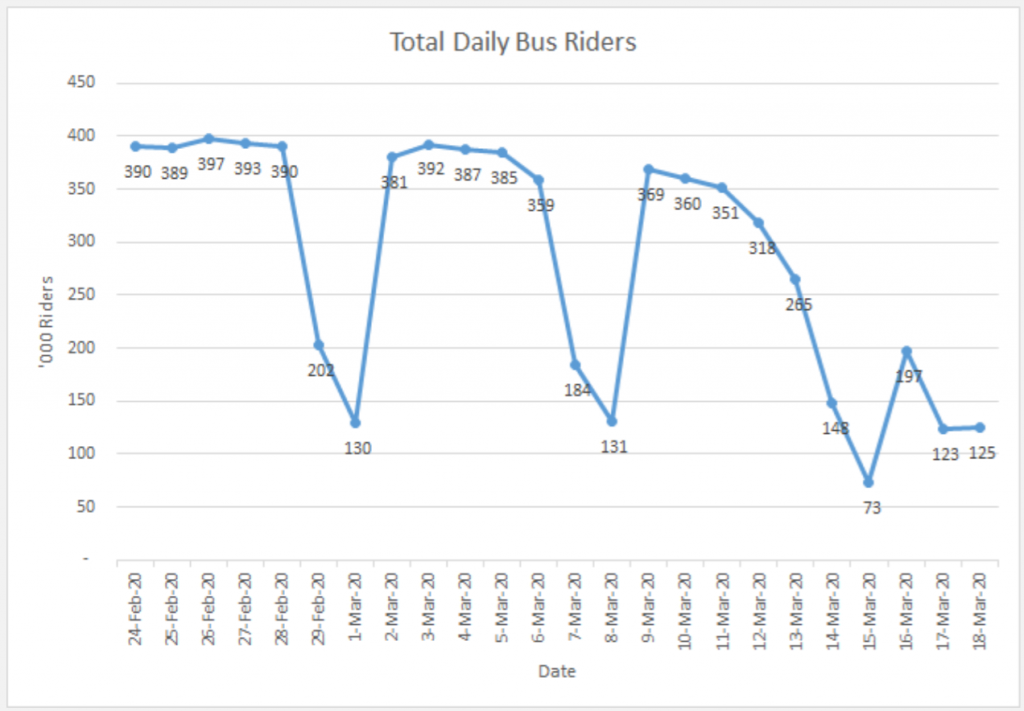

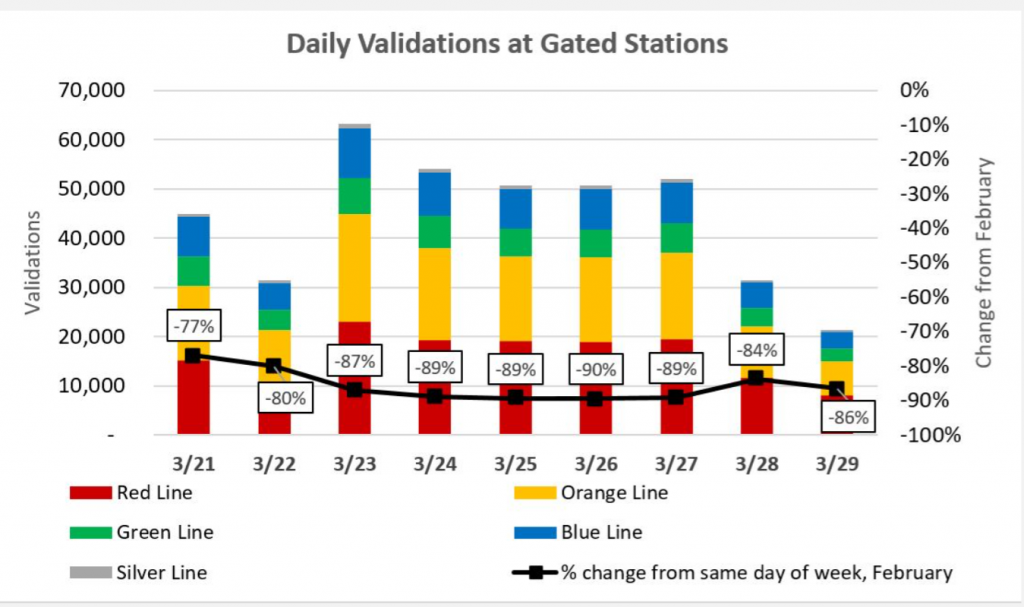

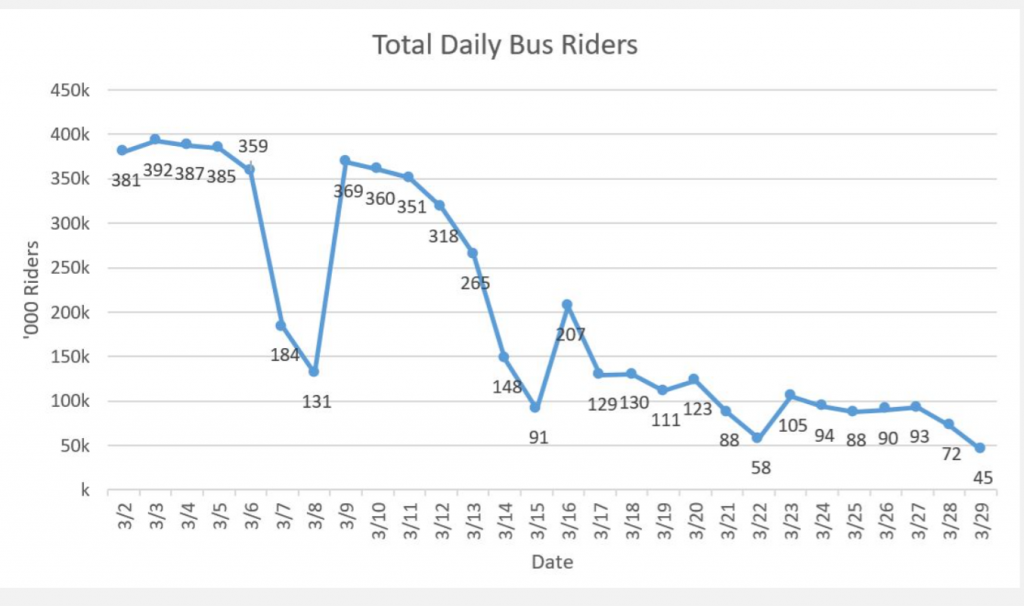

While the MBTA scaled back its schedules in an effort to ensure the agency could continue to provide service for essential trips while promoting emergent best practices in health and safety protocols, rail ridership dipped to 90% below the pre-pandemic baseline, while bus ridership similarly faltered:

Since late April, ridership levels have slowly, but steadily, begun to rebound, increasing between 5 – 15% each week:

Despite these gains, the system is still operating at approximately 80% below pre-pandemic baseline ridership, and now faces a looming long-term financial crisis.

A June report by the Massachusetts Taxpayer Foundation estimates that the MBTA’s budget shortfall could reach $400 million for fiscal year 2022, which begins on July 1, 2021. MBTA officials, who don’t believe ridership will bounce back to pre-pandemic levels until the summer of 2022, have predicted a deficit between $308 – $577 million, depending on how quickly riders return, whether the agency is able to reallocate federal pandemic funding, and assistance it may receive from the state legislature.

In anticipation of this deficit, the MBTA’s Fiscal and Management Control Board unveiled a plan on Monday to guide its decision-making process regarding future changes in service. “Forging Ahead” seeks to lay the “foundation for the transit service that will power an equitable and sustainable economic recovery for Massachusetts.” While the plan begins to contemplate various scenarios involving permanent, large-scale changes in service, the MBTA will spend the next several months assessing service levels and demand by route and line, and will incorporate stakeholder feedback throughout the process.

Although the pandemic has forced us to change the ways we think about and engage with the world, it offers an unparalleled opportunity to fully reimagine and rebuild systems and institutions from the ground up, across sectors, with better data-driven understandings of how to incorporate equity and sustainability to build a better future for everyone.

A CLF petition entry from me made it your way. I didn’t know you’d receive it. They were vague about where it was going. Thanks for your quick response, anyway.

It seemed to imply the cuts might be permanent. I’m mostly fine with temporarily adjusting service levels down during the pandemic, except…

1. if employees are let go, staffing up again when things return to normal would be hard I would think.

2. staff let go in this job market don’t leave the state’s (our collective) responsibility. If we don’t provide temporary income to people through the MBTA until they are needed again, to some degree we’ll have to pay into rental assistance programs and donate to the food bank for those who don’t find other work. Related to that, layoffs are the opposite of stimulus from a state economy perspective.

But long term, I hope no one is assuming there will be continued working from home requiring lower levels of T service. That’s entirely an unknown and should not be counted on.

If the thought is that people will instead shift to electric cars (I recall you concluding that the T isn’t much of an answer to climate emissions given its ridership levels vs. driving trips before the pandemic)…

1. this is not affordable by many of those who would have taken the T before.

2. we’d better get cracking on those charging stations, grid expansion in support of offshore wind, and distributed grid and storage technology while we ramp up solar. There are papers on ISO NE’s website suggesting we are limited in how much wind power we can absorb given the current grid:

https://www.iso-ne.com/system-planning/system-plans-studies/economic-studies/

Also on that site is the depressing statistic that we’re only at 10% renewable (not including hydro IIRC) with 2/3 of that being burning wood and trash. Seems a sham to call burning wood renewable, depending on how it’s sourced. So the coming weeks will see the merging of the Senate’s climate bill and the House’s? What is going on these days on the climate front?