NOTE: THIS POST IS OBSOLETE.

IT HAS BEEN CONSOLIDATED INTO THIS POST.

This post adds an important point that was missing in my recent post on heat pump economics: Electric rates for municipal light customers and municipal aggregation customers are materially lower than for customers of investor owned utilities (“IOUs”) . For those municipal customers, heat pump conversions are more attractive economically. 176 out of 351 Massachusetts communities have adopted aggregation programs and 50 are served in whole or in part by municipal light companies.

The recent heat pump economics post concluded that:

Even for a conversion from an oil burner, consumers should not count on operating savings from a heat pump conversion and should recognize the risk of cost increases.

That conclusion, valid for customers of investor-owned utilities, should be qualified by the following further statement:

In the many municipalities with their own light department or a municipal aggregation program, the probability of operating savings is high, although cumulative operating savings may remain modest as compared to the capital costs of a heat pump conversion.

Heat Pump Economics in a Sample Municipal Light Community

The cost estimates in the recent heat pump economics post are based on the statewide average electric rates published by the Massachusetts Department of Energy. Those rates are load weighted averages for the major utilities and they reflect the rates for a large share of the consumers in the state.

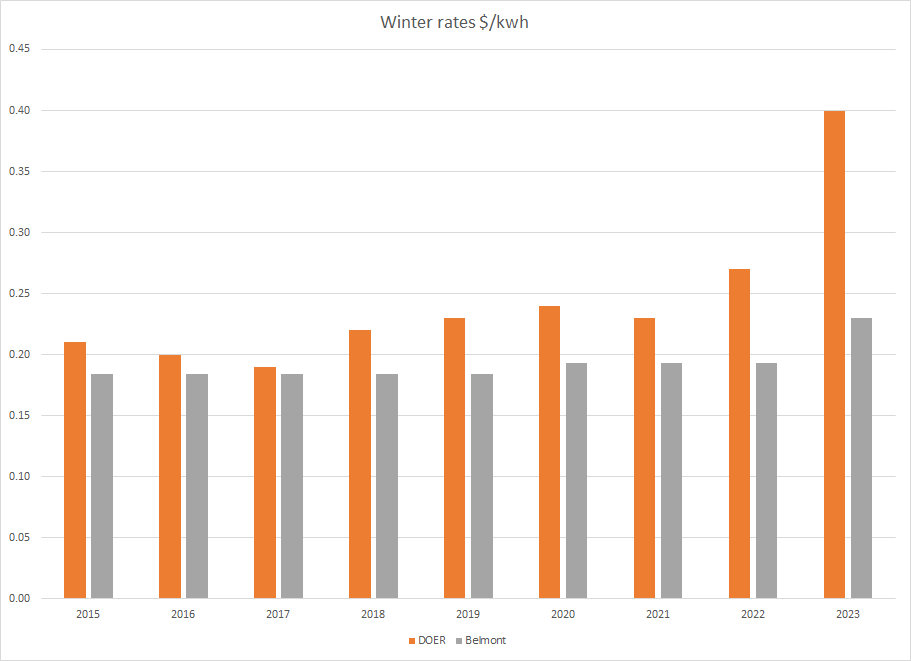

However, municipal light customers generally experience lower rates. As an example, the chart below compares Belmont Light rates to the DOER statewide average rates over the past 9 winters.

Winter Electric Rates: Belmont Light vs. DOER Average

Belmont Light explains the rate differential as due to:

. . . Belmont Light’s ability as a municipal light plant . . . to sign long-term power contracts and not-for-profit business model . . .

Belmont Municipal Light Winter Rate Increase Annoucement (2023)

As a policy matter, we might want to re-examine the policy that bars the investor owned utilities (IOUs) from entering long-term contracts. Certainly, in 2022 and 2023, the short-term contracts are working out especially badly, reflecting a rapid spike in energy prices. On the other hand, in a falling price environment, a long-term contract will look worse. The chart does show that even in more normal years, municipal rates have been lower than IOU rates. There does appear to be a consistent statewide pattern that municipal average monthly bills have been lower than IOU average monthly bills (although we lack a direct comparison of rates and some of the difference is due to the exemption of municipal light plants from contributing to statewide energy efficiency efforts).

The difference in rates has a material effect on the economics of a oil to heat pump conversion. Using the same assumptions as in the recent heat pump economics post (250% heat pump efficiency, 85% oil heat efficiency), the chart below compares the annual operating cost savings for heat pumps versus oil heat.

Heat Pump Advantage over Oil: Computed using Statewide Electric Rates vs. using Belmont Electric Rates

| Winter Ending in Year | Heat Pump Advantage over Oil: Annual Savings ($) at DOER Average Electric Rates | Heat Pump Advantage over Oil: Annual Savings ($) at Belmont Light Electric Rates |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 181 | 396 |

| 2016 | -306 | -176 |

| 2017 | -19 | 27 |

| 2018 | -13 | 285 |

| 2019 | 75 | 457 |

| 2020 | -255 | 139 |

| 2021 | -429 | -119 |

| 2022 | 21 | 667 |

| 2023 | 27 | 1,458 |

| Sum over nine years | -719 | 3,134 |

| Average over nine years | -80 | 348 |

Belmont light rates and computations appear in the spreadsheet linked to at the bottom of the post.

The unusual market conditions in the 2022-2023 winter — which favor long term power contract holders — explain roughly half of the apparent difference between the heat pump advantage at the municipal utility rates as opposed to at statewide rates. Yet, the advantage is material even omitting 2022 and 2023.

Community Choice Electric Programs

Community choice electric programs — formally known as “municipal aggregation” programs — allow customers within a municipality to participate in bulk purchasing of power. Consumers participating in these programs pay a municipally determined charge for supply of power, but continue to pay the investor-owned utility for delivery of power. Arlington, Cambridge, Watertown, and Boston all offer these programs — purchasing power in bulk and reselling it to their residents with Eversource as the delivery and billing agent. These programs are currently attractive as compared to relying on Eversource for both supply and delivery as the chart below shows.

January 2023 Community Choice Electric Rates (excluding delivery charge)

| Community choice rate | Winter 2023 generation/supply charge (cents/kwh) | Year of program launch |

|---|---|---|

| Arlington Basic | 16.090 | 2017 |

| Boston Optional Basic | 10.900 | 2020 |

| Cambridge Standard Green | 10.200 | 2017 |

| Watertown Basic | 12.723 | 2019 |

| Memo: Belmont Light Basic | 11.000 | 1898 |

| Comparison: Eversource Basic | 25.776 | 2015 rebranding |

These programs are all relatively new. It will take some time to get a better sense of their performance as a class statewide. It is too soon to make judgments about the spread below IOU supply rates that they will be able to maintain. People in these communities will still need to pay delivery charges to an IOU. Those charges may run a several cents higher than municipal light charges, in part due to the statewide assessment for Mass Save.

It certainly appears that these programs will help make electrification projects more attractive, but it remains to be seen by how much.

Benefit-Cost Ratio Computations

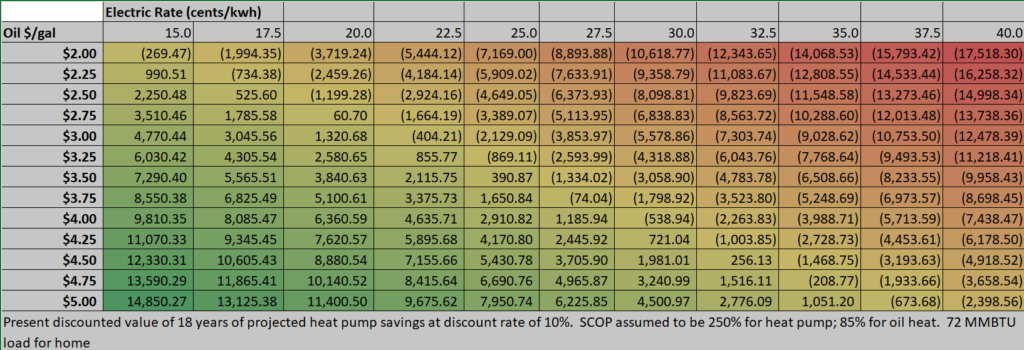

One way to think about a project is to compute a present value of the future savings stream generated by the project and compare it to the cost of the project. The chart below uses the standard “present discounted value” method with a discount rate of 10%. The 10% discount rate reflects both the cost of capital and the likely high variability of the future savings stream, which is dependent on the fluctuating relationship between rates. (The 10% rate is not entirely arbitrary, but the judgment behind it is weak. Interested readers can experiment with alternative discount rates using the spreadsheet linked to at the end of the post.)

The chart shows how the present value of expected savings depends on energy prices. In the darker green, lower left corner of the chart, one finds the best case operating savings for a heat pump conversion, reflecting a low municipal electric rate of 15 cents/kwh (Braintree is near this level) and very high oil costs (costs spiked over $5/gal earlier this winter). In that scenario, the savings stream, if held constant for the life of the pump (not realistic) could offset $14,850.27 of upfront costs. In the far right column on the chart one sees that heat pumps generate operating losses at any likely oil price when electric rates are at 40 cents/kwh (approximately the state IOU average this winter).

Present value of heat pump savings over oil heat under alternative rate scenarios — rates held constant over 18 year heat pump life.

The upfront costs of whole home heat pump installations are currently running in the $25,000 to $30,000 range according to good anecdotal evidence. With a Mass Save incentive for a whole home heat pump of $10,000, the operating savings in the most favorable, lower-left scenarios could almost bridge the gap. Unfortunately, municipal light customers who use oil are not eligible for the generous Mass Save whole home heat pump incentive.

And it’s obviously unwise to assume that the current extreme market conditions will continue. Over an estimated 18-year life of the heat pump, it’s hard to know how relative rates will change. Assuming middling conditions (the central area of the chart) may be wisest since the savings will average out over price fluctuations.

Each homeowner’s decision is different: If one was near end-of-life for both an oil heat system and an air conditioning system, and could therefore include the cost of both their replacements in the benefit-cost computation, then the benefit-cost ratio could be favorable with available incentives. Using the smaller saving numbers near the middle of the chart, the operating savings would have a relatively modest impact on the decision.

Even if available operating cost savings are not great enough to tip a raw benefit-cost analysis in favor of heat pumps, they can help make a carbon-motivated decision easier.

Summary

In communities with municipal light plants or municipal aggregation programs, electric rates are lower and heat pump adoption likely offers operating cost benefits.

Additional Sources

Computations and additional links appear in this spreadsheet.

Greetings, Senator,

Thank you for sharing this material — so very much appreciated.

I particularly welcome your explanation and elaboration on all of the factors impacting these calculations/decisions – most helpful, to inform future decisioning.

One aspect I would offer that might be helpful as discussion (zoom?): your note “As a policy matter, we might want to re-examine the policy that bars the investor owned utilities (IOUs) from entering long-term contracts. ” I am not quite sure what this means (what is the policy, what impact it has), and sounds like a path for legislative opportunity…

Thanks again for most useful information and analysis!!

Jim,

In 1997 the Legislature passed electric utility restructuring legislation. This legislation led to the breakup of the vertically-integrated utilities (this only applied to IOUs, municipal light plants were excepted). No longer would utilities own generation assets and also deliver the energy. Rather, they would become ‘wires and poles’ companies and the new owners of generation would compete to supply energy to customers. This competition was hoped/expected to result in least price electricity for customers. However, it was understood that this competitive supply market for electric customers would take sometime to develop so the Legislature created a fall-back, originally called ‘default service’ and now called ‘standard service.’ As part of this service, the IOUs were allowed to purchase energy to supply those customers that hadn’t chosen to migrate to a competitive supplier. But, because the Legislature did not want the IOUs back in the energy side of the business, IOUs were explicitly limited to short term market purchases (basically for six months periods). Now, 25 years later, many IOU customers, particularly residential customers, remain on utility standard service, with the result that they are being hit with huge price increases given the unprecedented increases in short term energy costs. Allowing IOUs to enter into longer term contracts to supply standard offer service undoubtedly would have at least somewhat smoothed out the huge rate increases seen recently. However, allowing IOUs to enter long term contracts as a general matter (there have been exceptions permitted by the Legislature) is inconsistent with the 1997 electric utility restructuring and would certainly be very much opposed by competitive suppliers.

Please work on assuring our power plants will be able to function.Roaming blackouts are in the near future, as we load the power plants with electric vehicles being charged,heat pumps,inverters,etc.

We need to build our infrastructure,not our individual homes, first.Only our elected officials can help get this done.This is where we need your efforts focused.

We are asked to conserve,buy energy efficient products. As we help to reduce the burden on our power plants (which is why these incentives are in place) we are pushing power plants to handle more power requirements than less.

This does not make sense.We must solve the big issue of creating reliable infrastructure, which will lead us to how we power our homes.

Please get our infrastructure in order.

If you cannot get the power plant to produce electricity, your heat and power requirements are a mute point.

Time to get our infrastructure as the priority issue.

Could the legislature impose an oil based fee or tax to tip the scales? I’d see this both for end consumers and those running power plants supplying wholesale electricity to the grid. The latter is motivated by the observation by Bruce Mohl in his Commonwealth article pointing out how near Christmas Hydro Quebec failed to deliver a large amount of power during a countrywide cold snap. If I remember rightly the spot price of gas went so high that plants that could burn gas or oil switched to the latter based on it being cheaper to burn as opposed to our pipelines and LNG terminals not having sufficient gas. Would be good to manipulate the economics in said situations.

Thanks for this additional analysis. Right now, my electricity cost (municipal aggregation) is .333 cents/kwh. MADER reports the average retail heating oil price this week is $4.56/gallon. So, for me that is pretty close to breakeven between using oil heat and using my heat pumps / mini-splits. I’ll add that the municipal aggregation price is for three years, so if oil prices fall from $4.56/gallon during that time (which I think is more likely than not), I will be in negative territory using my heat pumps. Even if oil stays steady, I will never recoup the approx $30,000 cost of the heat pumps / minisplits.