Governor Baker’s transportation bill responds to the widespread sense that we need to keep accelerating our investment in transportation — to relieve congestion, to assure safety, reliability and climate resiliency and to support planned development.

In his press release, he said “This bond bill reflects our ongoing commitment to increasing the capability of MassDOT and the MBTA to carry out construction projects to ensure that residents throughout the Commonwealth have access to safe and reliable travel options.”

The back story is more or less consistent with that hopeful headline, but the ongoing questions are: “Are we doing enough?” and “Are we doing as much as we can?” I’m pretty sure the answer to the first question is “no,” and I hope the answer to the second question is also “no.” This post is just a collection of notes on how to understand the transportation bond bill and capital spending plans.

What is a bond bill?

A bond bill is not a “plan”. A bond bill is simply an authorization for the Commonwealth to borrow money in broad categories over a period of years. Typically, the Governor requests and the legislature grants bond authorizations for various purposes including transportation that go far beyond the amount of debt that the state can actually afford to issue. These authorizations are valid for five years unless extended or re-extended for longer periods by a particular bill. Multiple authorizations for the same purpose may be open at the same time.

The amount of authorized but unissued debt dwarfs the Commonwealth’s actual spending plans. According to a report compiled by the House Committee on Bonding and Capital Assets, authorized but unissued debt peaked at just under $30 billion in 2015. As of the end of fiscal 2018, the Commonwealth had $27.4 billion in debt outstanding, but still had another $20.8 billion authorized but unissued, including $11.1 billion for highway purposes. See the Commonwealth’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for FY18, Note 7.G. By comparison, the capital spending plan of the Commonwealth in FY20 only calls for $2.7 billion in expenditures from bonding (p.17).

Information on capital spending and authorizations is, of course, publicly available. The Treasurer’s information site for bondholders provides a complete inventory of bond authorizations. This spreadsheet prepared by the Comptroller of the Commonwealth breaks down the spending and outstanding authorizations at the account level for transportation bonds as of September 4, 2019. At the sub-fund roll-up level, this report shows just the outstanding authorizations, but for all types of bonds for the same date.

How is debt actually limited?

Other statutes and policies limit the total amount of debt that the Commonwealth can issue to levels well below bond bill authorizations. The total outstanding direct debt of the Commonwealth is limited by statute. The limit was lowered to $17.070 billion for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2011 and grows 5% each fiscal year. Since then, the amount of debt outstanding and subject to the limit has fluctuated between 2.1% and 6.3% below the limit. Certain short term and special obligation bonds have been exempted from the limit by their authorizing statutes; these include school building bonds, convention center bonds and, most significantly, several categories of transportation bonds. See the Commonwealth’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for FY18, Note 7.I and page 198.

Additionally, a statutory Capital Debt Affordability Committee makes an annual judgment about the amount of debt that the Commonwealth can prudently issue. The Committee’s statutory scope of concern extends to all tax-supported debt, but the committee typically opines only on the amount of general obligation debt that the Commonwealth should issue. The Capital Debt Affordability Committee has developed a three part test to determine the amount of general obligation debt that the Commonwealth can safely issue in the coming year. First, it projects debt service and tax revenue and seeks to keep future debt service below 7% of revenue. Second, it checks that debt will not exceed the statutory fixed maximum. Third, it limits growth in outstanding balance to $125 million.

The first criterion — the limitation of projected debt service to 7% of revenue — makes the basic prudential decision as to how much of the state’s revenue should be allocated to supporting borrowing. Defining and applying this criterion involves fundamental judgments about how good to feel about the state’s fiscal health over the long term. It requires assessing the Commonwealth’s ability to pay debt service in the context of (a) competing uses of increased revenue for state operational spending; (b) regional and national economic trends; (c) likely future interest rates; (d) overall public sector borrowing and spending including municipalities and quasi-public agencies; (e) overall public sector liabilities including pension and post-retirement health care liabilities to employees. These assessments ultimately involve some guess work guided heavily by the response of rating agencies. See additional discussion by the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation here.

In Fiscal 2020, the committee determined that the Commonwealth could issue $2.43 billion in general obligation debt. This “bond cap” is the most significant limit on the Commonwealth’s capital plan, keeping actual borrowing well below unissued authorizations. The legislative practice of leaving in place huge unissued authorizations gives the Governor enormous latitude as to which kinds of projects to advance with available new debt under the bond cap.

For Fiscal 2020, the Governor allocated available bond cap funds as follows:

| Agency/Secretariat | FY20 ($millions) |

| Massachusetts Department of Transportation — MassDOT (including MBTA) | 1,030.0 |

| Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance | 517.7 |

| Department of Housing and Community Development | 237.5 |

| Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs | 231.4 |

| Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development | 210.4 |

| Executive Office of Technology Services and Security | 125.2 |

| Executive Office of Administration and Finance | 36.7 |

| Executive Office of Public Safety and Security | 22.0 |

| Executive Office of Education | 19.0 |

| Total | 2,430.0 |

What are the sources of funds for transportation capital spending?

For MassDOT’s capital investment plan ( text only version of same document here), the primary sources of funding are the bond cap allocation and federal highway funds.

| MassDOT Funding Source | FY20 ( $ millions) |

| Federal Funding (mostly Federal Highway) | 819.5 |

| Bond cap allocation | 854.8 |

| Tolls | 156.6 |

| Other state sources | 54.2 |

| Total Capital Spending | 1885.1 |

The MBTA’s capital plan is separate from MassDOT’s, although it is presented in the same document and uses some of the same sources of funds and several additional sources.

| MBTA Funding Source | FY20 ( $ millions) |

| Federal Funding ex. Green Line Extension (mostly Federal Transit) | 410.3 |

| Federal Funding for Green Line Extension | 320.5 |

| Bond cap allocation (South Coast Rail) | 115.2 |

| Bond cap allocation ( annual assistance) | 60.0 |

| Rail Enhancement Bonds | 233.2 |

| MBTA Revenue Bonds | 107.6 |

| Positive/Automatic Train Control Financing | 99.9 |

| Transfer from Operating | 90.0 |

| Other state sources | 33.7 |

| Total | 1470.4 |

The online version of MassDOT’s FY2020-2024 capital plan provides a good view of each of these pieces. However, it does not show how the proposed bond bill dovetails with the capital plan and how the proposed additional authorizations in the bond bill are expected to combine with existing outstanding authorizations to provide available funds over the coming decade. As noted above, there is approximately $10 billion in authorized but unissued transportation bonding capacity, so it does appear that the combination of existing and new authorizations will give a lot of flexibility for evolution of the capital plan in the coming years.

As to funds generated by general obligation debt subject to the bond cap, the authorizations are never the limiting factor, as discussed above. The plan makes clear commitments as to the amount of bond cap funding that will be provided, roughly $1 billion per year — $100 million more than planned in the previous rolling edition of the capital plan. The relationship of special obligation debt plans to outstanding authorizations may be tighter and is not examined in the plan.

The special obligation credits available for transportation spending include:

- Borrowing against future federal grants. Investors are willing to trust the federal government will come through with continued transportation grants. These Grant Anticipation Notes have been rated AAA by S&P.

- Borrowing against the revenues of the Commonwealth Transportation Fund — primarily the gas tax and Registry of Motor Vehicle fees. The Rail Enhancement Bonds and some of the Accelerated Bridge Program bonds are secured by the CTF. A portion of the CTF revenues is committed to payoff older gas tax bonds. By statute, as long as bonds are outstanding under this credit, taxes and fees may not be reduced below their level at the time the bonds were issued. The trust agreement for the bonds is slightly looser requiring only that fees continue to provide four-fold coverage of debt service. Additional bonds may be issued up to this four fold coverage level.

- Revenue bonds of the MBTA (not technically obligations of the Commonwealth) — pledges of sales tax, assessment or parking revenue. Debt service on bonds issued against these credits comes out of the same larger pot as the T’s operating expenses, so increased borrowing against these credits must be approached with caution.

It would appear that these three credits provide more than sufficient headroom for the FY2020-2024 capital program:

- According to Moody’s report on the 2017 GAN issuance, the commonwealth “expects to receive approximately $600 million annually” in pledgeable grants. The coverage ratio after issuing another $143 million per that 2017 issuance would stand at 5.5x for federal funds alone — that would allow a further approximately another $250 million in borrowing while keeping the federal funds coverage under 4x. The credit also benefits from a subordinated interest in CTF revenues which raises the total coverage to 15x. It is unclear how rating agencies would react to a significant increasing in borrowing against both the GAN and the senior CTF credits, but it seems safe to say that there is hundreds of millions, perhaps over $1 billion, of unused GAN borrowing capacity available over the next five years, but the capital plan does not contemplate use of that capacity.

- As of the end of 2018, outstanding CTF bonds stood at $3.1 billion and the debt service coverage was just under 8x, suggesting that the credit could support very approximately $3 billion more in borrowing before reaching the 4x minimum coverage ratio. With interest rates trending down and revenues stable, the borrowing capacity could be even greater. The FY19 planned spend and the FY20-24 planned spend against the CTF credit (REB and ABP bonds) add up to only $2.125 billion, suggesting that as much as an additional billion could be raised above and beyond planned levels for the next five years using the CTF credit without raising revenues pledged to the fund.

- It is harder to judge the amount available under the MBTA’s own revenue bond borrowing capacity, both because of the complexity of the MBTA’s debt covenants and because of the competition of new debt with operating priorities. The capital plan already assumes $1.0 billion in new MBTA borrowing over the next five years and I would not make the argument that the MBTA itself should carry debt beyond that already planned.

There is a new source of revenue which may become available to support certain transportation projects — the Transportation Climate Initiative. The TCI is the fee on transportation carbon emissions that is currently under regional negotiation. Section 113 of the proposed transportation bond bill would allow the transfer to the CTF of up to one half of the proceeds of the TCI revenues. Negotiations are still in progress, so it is too early to put a number on those proceeds, but the order of magnitude is in the hundreds of millions. A new credit built on the CTF including TCI funds could allow the Commonwealth to raise as much as another billion for transportation projects assuming a 4x coverage ratio, level principal payments with a 20 year maturity, a 2% interest rate and $280 million in TCI revenues delivered to the CTF.

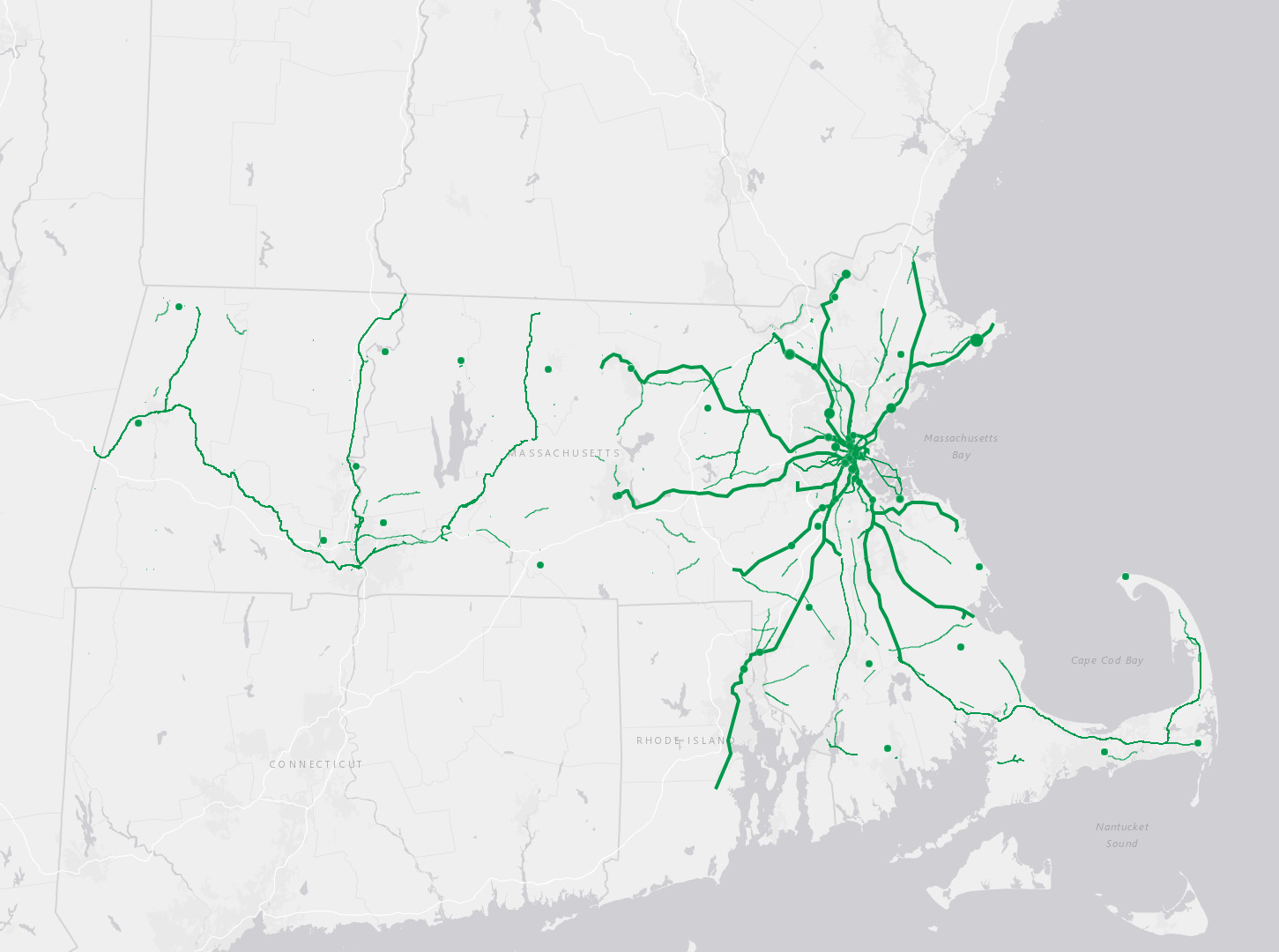

What is MassDOT’s Capital Spending Plan?

2009 transportation reform legislation required MassDOT to develop a 5 year capital plan and MassDOT held public meetings in 2010 for the first five year plan, FY2011-2015. The planning process has gotten more and more rigorous since then. The total number of public feedback meetings around the plan has gone from 3 to 13 and the depth of analysis has continued to improve.

Several documents are useful for understanding the current plans for capital spending.

- The FY2020-2024 capital planning document is as user-friendly as it can be, but the capital plan is voluminous and the document is daunting.

- MassDOT’s blog offers a more succinct overview of the spending side of the plan.

- The presentation given to the MassDOT board at their meeting to approve the plan on June 17 emphasizes the public process. Their discussion is also worth listening to — view the live stream starting at 1:54.

- The Governor’s press release on the transportation bond bill offers an overview of intended uses of the funds from the proposed bonds; that statement ties loosely to the capital plan although, as noted above, the full crosswalk of old and new authorizations to spending plans is unclear.

Interested readers should review those documents, but here are the observations that jump out for me.

- Planned transportation capital spending continues to increase — the total capital plan proposes $18.3 billion in spending, up from $10.3 billion in first 5-year plan in for FY2011-2015.

- Overall, the 5-year spending plan still emphasizes reliability and modernization as opposed to expansion — $8.1 billion for reliability, $5.2 billion for modernization, $3.0 billion for expansion.

- Overall, spending is roughly evenly split between roads and transit and other modes, with $8.3 billion spent on the MBTA and $10.1 spent through the rest of MassDOT, most of which is roads, but which also includes Regional Transit Authority spending, some rail spending, and bike/ped spending.

- The biggest projects in the plan are MBTA projects. 5 projects account for 3/4 of the MBTA’s capital plan for the next five years.

- A total of $2.5 billion in new vehicles and improvements for the Red Line and the Orange Line.

- The Green Line extension at $1.4 billion.

- The South Coast Rail project at $1 billion (full funding of Phase I)

- $0.9 billion for the Green Line Transformation — a collection of track, power, signal and vehicle investments that will upgrade service on the Green Line

- $0.5 billion for commuter rail safety and resiliency, mostly train control improvements, including the new federally mandated Positive Train Control technology.

- Buses are less expensive and do not surface as major investments, but the plan details do include a number of bus investments.

- $224 million for delivery of 460 40ft Buses – FY 2021 to FY 2025

- $125 million for a bus maintenance facility

- $52 million for procurement of electric buses and related infrastructure

- $135 million for procurement of hybrid buses (“option order”)

- $35 million for service plan optimization and $2.6 million for the Bus Service Replacement Plan (Better Bus Project).

- On the highway side, the spending is spread across more projects, but work on the I-90 interchanges at 495 and Allston-Brighton standout.

- A total of $2.3 billion in spending through municipalities, split roughly evenly between the general purpose Chapter 90 program and specifically approved projects, mostly projects approved through the MPO process.

- What is not in the capital plan is any significant investment in rail service expansion other than South Coast Rail. The North-South Rail Link is not in the plan and South Station Expansion is not in the plan at a high level of spending — still at the planning stage. Once the Rail Vision Study makes its recommendations this fall, we will need to turn to scoping and funding the investments that that study suggests are most valuable.

In conversation after conversation that I have had with people close to the transportation spending process, it seems clear that officials at every level are pushing MassDOT and the MBTA to get capital projects out the door. Capital spending is not constrained by available funds but by the combination of other factors that limit progress on large projects — management bandwidth, public process, design complexity, permitting hurdles, limited capacity of construction contractors and equipment manufacturers, the need for oversight and quality control, the challenges of keeping the system working while repairing it.

Summary Perspective

It seems likely that the Commonwealth can get through the next five years of its planned and likely feasible additional transportation spending without new revenues, but it likely needs new bond authorizations that will expand debt levels that are already high in the eyes of rating agencies. Our transportation system capital needs will likely continue to expand as we work to reduce congestion, accommodate continued growth and adapt to climate change. An approach that funded more projects on a pay-go basis using new current revenues might be fairer and more prudent than spreading costs onto future taxpayers who are likely to face expensive new challenges.

Additional Resources (not cited above)

- MassDOT’s Debt issuance policy governing management of legacy MassPike debt

- Recent highway system bond prospectus — useful for understanding credit structure

- The MassDOT metrics Tracker — some perspective on capital project performance.

- Statutory authorization of Commonwealth Transportation Fund borrowing.

- Revenues and Expenses report for MassDot — not too useful for debt, but other sources interesting.

“Are we doing enough?”

Where is or at what point will this point be properly quantified by the relevant state departments and checked against an actual target? What I mean is, when do we put on our Greta Thunberg thinking caps and actually do an analysis starting from our CO2 emissions per capita now and modeling what our emissions will be in 2025 following this plan vs. alternative actions. The world is supposed to be at net zero emissions or better by mid century. With some regions making strong commitments about 2030 emissions targets, that the capital spending time range on this is half way there makes the lack of apparent emissions targets and the lack of ambition in getting alternatives to driving out there alarming.

If one were to back of the envelope estimate the effect of the capital spending plan on per capita emissions, I wonder what number would pop out. There’s some new capacity to come from the new subway cars, but what does “modernization” mean in terms of emissions reductions? Perhaps 2% drop in five years? So extrapolating to 2050 we might reduce our transportation emissions by 1/5? That whole electric car thing better work out really well and not end up being unrealistic like the old hydrogen car fantasy.

I may be missing it, but it seems like with transportation at least there is still no real target just a kind of vague “best effort” which isn’t best and, well, I suppose there was effort by those working on it, but it’s plainly dwarfed by the scope of the problem.