Lack of trust is the most significant barrier to a complete Census count in 2020. The Secretary of State is leading statewide efforts to build awareness about the coming Census, and I will continue to share information to support those efforts.

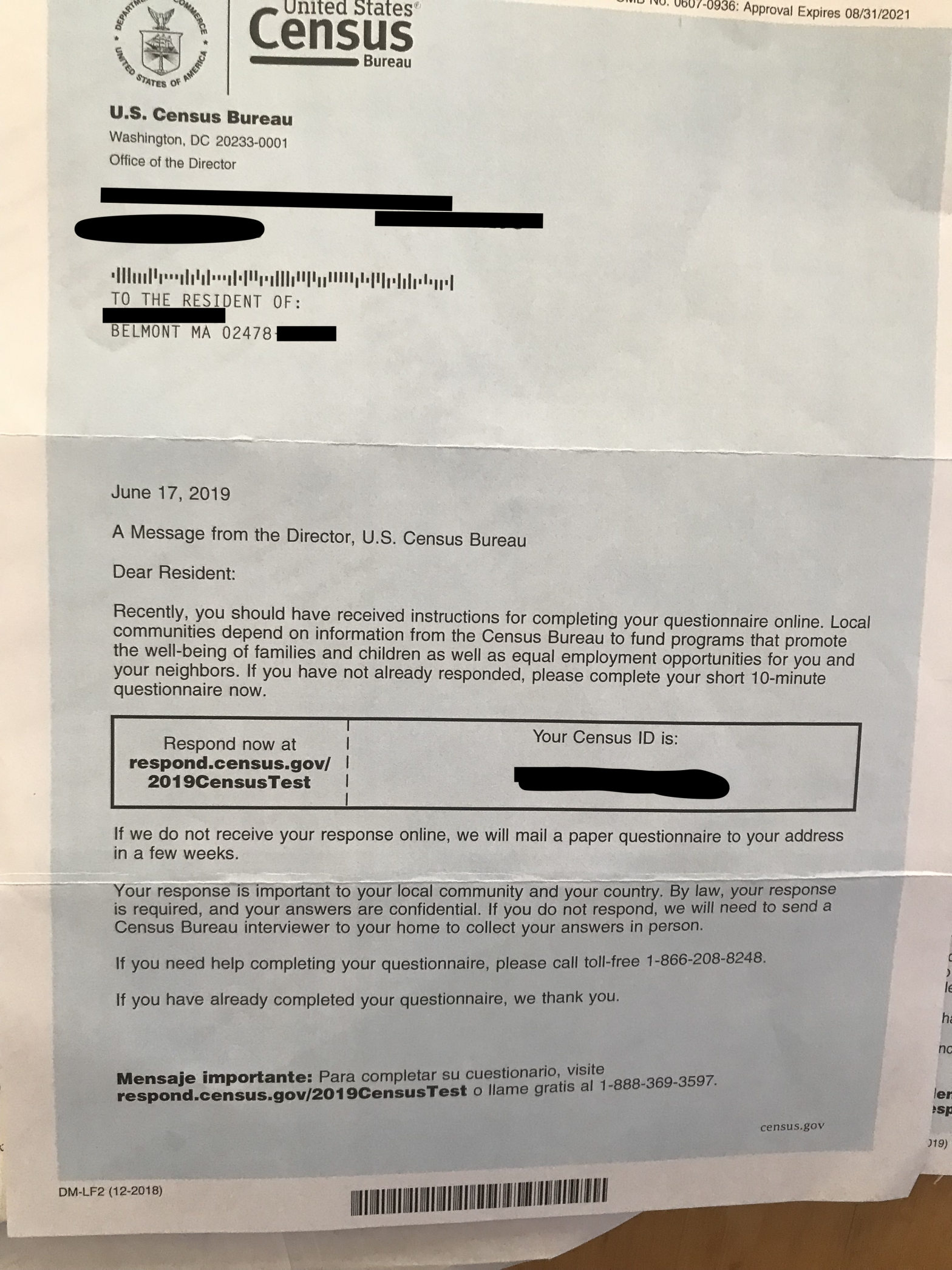

We are only months away from the 2020 Census, and Census Bureau personnel are already sending out test forms to some residents. I heard from one constituent who received one of these forms by mail asking if it was legitimate. This constituent is a well-informed native-born citizen with a lot of experience with government.

Residents who are not native born – whether properly documented or not — often greet Census Bureau outreach with even greater mistrust. The President’s daily rhetorical attacks on immigrants further elevate that mistrust.

The constitutional mandate of the Census Bureau is to count persons

“where they live and sleep most of the time” in the United States, with or without documentation. It will be harder for the Bureau to accomplish that in 2020 than in many of the past 23 decennial Censuses.

As hard as a complete count is going to be anyway, the Trump administration seems intent on directly interfering with the process with the goal of increasing the number of Republican representatives in Congress.

The number of representatives in Congress apportioned to each state is a function of the total Census count of persons in the state (without regard to immigration status). First, every state, even those that are smaller than the average Congressional district, gets at least one member in Congress. Then seats are allocated by a process designed to assure that Congressional Districts in all states are roughly the same in population count. Undercounting low-trust populations could lead to a state having less representation in Congress. To the extent low trust populations vote Democratic, then undercounting them will favor a Republican majority in Congress.

Further, the balance of Democrats and Republicans elected to Congress within each state depends heavily on how district lines are drawn. Congressional district lines are drawn to assure that the population of each district is equal. Lines will be drawn based on the block level Census counts that come out in April 2021. Again, if the Census undercounts immigrants or other minorities, then districts will be drawn that give them less representation in Congress.

Almost as soon as he took office, President Trump’s Secretary of Commerce began working to add a question about citizenship status to the Census. While citizenship questions have been included in some prior Censuses, in recent decades, Census Bureau officials have viewed the question as likely to depress response rates. In the 2020 climate, according to officials cited by the Justice Breyer (see page 9-13), the question could have a very great effect – perhaps depressing the count of immigrants by hundreds of thousands.

The Supreme Court just rejected the proposed question. The Secretary had explained his inclusion of the question as having been requested by the Department of Justice for analysis of citizenship in voting rights cases. But the Court found that this was a pretext since he shopped the idea to a number of agencies before finally getting the Department of Justice to request it. The Supreme Court said “[W]e cannot ignore the disconnect between the decision made and the explanation given. Our review is deferential, but we are not required to exhibit a naiveté from which ordinary citizens are free.” A recent expose in the New York Times traced the proposed question back to a now deceased Republican political operative. That expose was not part of the record before the Supreme Court, but certainly validates the court’s decision.

The question now becomes whether the Trump administration will allow the Census Bureau to move forward and do its critical and constitutionally-mandated job in a timely way. As Chair of the Senate Redistricting Committee in Massachusetts, I’ll be watching closely and continuing to share information.

Update as of July 11

The final outcome here is that the Trump administration did ultimately take the right course of action, allowing the census to forward without the citizenship question, instead studying citizenship patterns using administrative records.

Responses to Comments (added 2:30PM on July 5)

Based on the range of comments below, I thought I should follow up to clarify some issues.

Who gets to vote? The right to vote in national elections belongs to citizens – people who were either born citizens or have made a commitment to the United States and passed the naturalization test. States or cities could make a different rule for elections to their own offices, but that is not the question at hand and I personally support the fundamental idea that citizenship is a condition for voting.

Which persons count toward apportioning the seats in Congress among the states? The constitution states that representatives shall be apportioned to states based on the “whole number of persons.” In context it is clear that persons means everyone, whether or not they have the right to vote. There is little chance that this rule will change as a result of constitutional amendment or Supreme Court decision and I do not believe it should.

Which persons count toward drawing equal-population districts for seats in Congress within a state? It would be hard to defend using one count for apportionment and a different count for redistricting of congressional districts, so I expect that for congressional redistricting, the “whole number of persons” construct will endure. Conceivably, a state or locality could successfully defend using a different rule for its own elections, although I do not advocate that.

What difference does it make if immigrants (documented or undocumented) count equally with citizens in legislative apportionment and redistricting? Whether counted or not, the non-citizens don’t vote and therefore are not going to get as much attention from their elected representatives. The real consequence is that the voting citizens get a disproportionate vote: In a congressional district that has, let’s say 400,000 non-voting immigrants and 400,000 voting citizens, then the voting citizens get twice as much influence as the citizens in a district that consists of 800,000 voting citizens – they get 1/400000 of the representative’s campaign attention instead of 1/800000. Whether that favors Republicans or Democrats in any particular case depends on how the district lines are drawn and what group of citizens is placed in the same district as the non-citizen population.

Can we live with the possibility that any group of citizens might be overrepresented as a result of placement in a district with non-citizens? My answer is yes: To put the question in perspective, there are other common ways that a particular group of citizens can get outsized influence. For example, if citizens reside in a district that includes a large prison or is heavily populated by university students, who typically do not vote in state or local elections, then they will have an outsized vote. I would concede that over-representation of citizens (in districts with very high populations of non-citizens, prisoners or students) could go beyond reasonable levels, and I don’t dismiss the concern out-of-hand, but at this point, my view is that we should keep the rules simple and continue to redistrict based on the count of whole persons. And, of course, the census is used as a measure of economic and other needs as well as a measure of representation. The needs of the district are not reduced by the fact that some of the people counted in it are non-voting.

Why has the possibility of asking a citizenship question become a political issue? It does appear that some strategists in both parties believe that, while districts vary, citizens who are Democrats are more likely to be mixed in with non-citizens in neighborhoods with high concentrations of non-citizens. In other words, on average, it is Democrats who benefit from the existing “whole persons” rule. So, if the Supreme Court were to entertain the possibility of redistricting based on citizens only, instead of all persons, the change would advantage Republicans. Certainly, that was the theory of the Republican strategist most connected to the proposed question – Tom Hofeller. In my view, even a Supreme Court a couple of seats further to the right could not condone this approach for congressional districts: The constitution is clear that all persons count for apportionment and probably, indirectly, for federal redistricting. So the real advantages for Republicans of including the question would come if (a) asking the question were to scare non-citizens away from the census; (b) states were to be permitted to redistrict based on citizen counts.

Why shouldn’t we ask a citizenship question on the census form? There is nothing per se wrong with asking a citizenship question on the census form. It is certainly interesting information and has been asked in some prior censuses. The argument I find persuasive, based on the Supreme Court’s recent opinion, is that (a) because of the current climate of fear among immigrants (both documented and undocumented), asking a citizenship question would distort the basic count that is required by the constitution; (b) even if people in fear can be persuaded to complete the census form there is no reason to expect that they will answer a citizenship or documentation question accurately. Adding the question will overall degrade the quality of census responses without adding new accurate information. To the extent we are interested in citizenship rates for informational purposes, there are other administrative datasets that can give us insight. So, the informational benefit is outweighed by the loss of count accuracy.

Would the citizenship question tell us how many people are in the United States without documentation? No. It just asks whether a person is a citizen. If the answer is no, no more detail is requested.

While I have carefully considered the feedback I received on the issue, I respectfully continue to believe it is wiser to leave the citizenship question out.