This post offers some background on the suddenly relevant limit on state tax revenues, which will likely result in a credit to income taxpayers on the order of about $3 billion — a credit for taxpayers on their April 2023 tax returns equal to approximately 15% of what they paid in April 2022.

History

Chapter 62F of the General Laws — a limit on total state tax revenues was added as a result of a referendum in 1986. It followed the adoption of the Proposition 2.5 limit on local property taxation. Barbara Anderson of Citizens for Limited Taxation led both referendum campaigns. There was confusion about a legislative alternative to the referendum. These letters to the editor clipped from the November 24, 1986 edition of the Boston Globe (as appearing at Newspapers.Com) illustrate the conversation.

Mechanics of Chapter 62F Today

What is limited?

The law seeks to limit state tax revenues broadly. It defines state tax revenues as:

the revenues of the Commonwealth from every tax, surtax, receipt, penalty and other monetary exaction, and interest in connection therewith, including but not limited to, taxes and surtaxes on personal income, excises and taxes on retail sales and use, meals, motor vehicle fuels, businesses and corporations, public utilities, alcoholic beverages, tobacco, inheritances, estates, deeds, room occupancy and pari-mutuel wagering; . . .

MGL, c. 62F, s. 2

Appropriately, however, the law excludes:

federal reimbursements, proceeds from bond issues, earnings on investments, tuitions, fees, service charges and other departmental revenues . . .

MGL, c. 62F, s. 2

How is the limit computed?

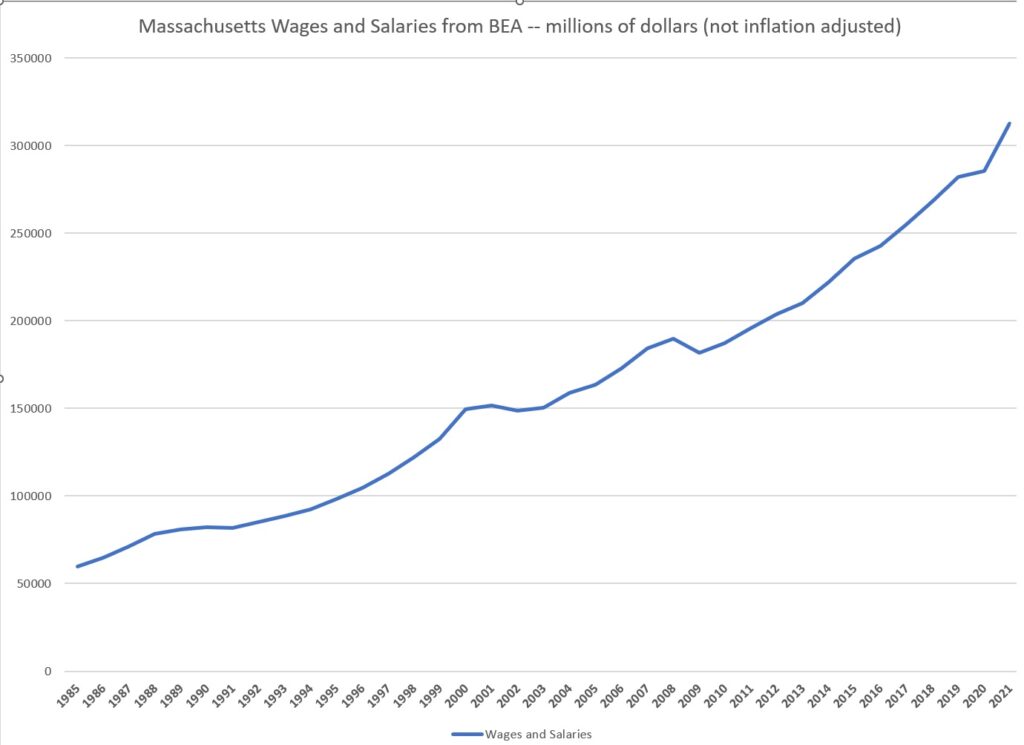

In essence, the law assures that state tax revenues do not grow faster than wages and salaries in Massachusetts.

Wages and salaries for the state are computed by the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis. This is a long-term time series, published in a consistent manner.

The law computes a ceiling on allowable state tax revenue for each fiscal year by increasing the prior fiscal year’s ceiling by the average growth in wages and salaries over the prior three calendar years. This computation has been chained forward from the starting point in 1986.

The law is conceptually tied together with Proposition 2.5 (enacted six years earlier in 1980), so that if the state were to allow new local tax revenues, they would count against the state tax limit.

Allowable state tax revenues for a fiscal year shall be reduced, if, after the effective date of this chapter, by an enactment of the general court, authority is granted to local governmental units by local option or otherwise to impose or levy a new, or to increase an existing, tax or excise.

MGL ch 62F, s. 4

How has the limit worked out?

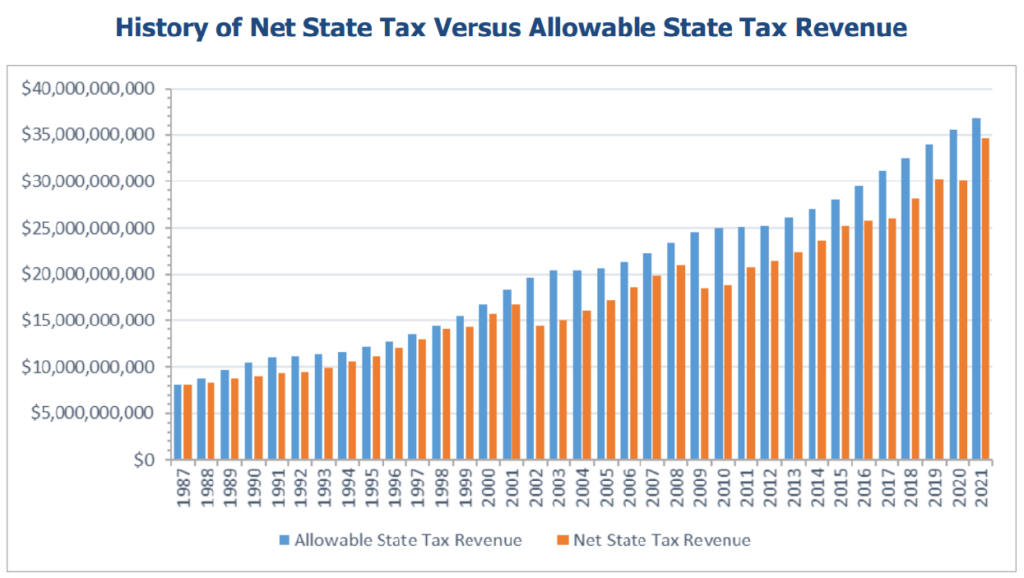

The graphic below shows that until 2022, the computed limit had come out above the actual revenues since 1987. (‘Net’ state tax revenues are state tax revenues less any abatements or refunds.)

Who computes the limit?

The limit is to be computed initially by the Commission of Revenue and reviewed and recomputed by the State Auditor. The State Auditor’s conclusion is final. See MGL c. 62F, s.5. The Auditor produces an annual report of her finding which cumulates the results of prior computations. The most recent report appears here.

When is the limit computed?

The limit is to be computed quarterly by the Commissioner of Revenue, but finalized in September for the preceding fiscal year. So, the limit for Fiscal 2022 (July 1, 2021 through June 30, 2022) is to be finalized in September 2022. The Fiscal 2022 limit is the Fiscal 2021 limit increased by the average of the annual growth of wages and salaries for the preceding three calendar years (2019, 2020, 2021).

What happens if there is an excess in state tax revenue?

The Commissioner of Revenue is to give taxpayers a credit on their current year’s state income taxes based on how much state income tax they paid in the immediately prior year.

If net state tax revenues in any fiscal year exceed allowable state tax revenues for said fiscal year the amount of such excess, as determined by the State Auditor and reported to the Commissioner pursuant to section five of this chapter, shall result in a credit equal to the total amount of such excess. The credit shall be applied to the then current personal income tax liability of all taxpayers on a proportional basis to the personal income tax liability incurred by all taxpayers in the immediately preceding taxable year.

MGL c. 62F, s.6.

So, after the final computation for Fiscal 2022 which should occur this September, taxpayers will receive a credit on their calendar year 2022 income taxes. This language does not contemplate the sending of checks, but rather a credit that people will have available when they file their taxes for 2022 in April 2023. This is the procedure that was followed in 1987 when the limit last forced a revenue reduction. See Auditor’s 2021 report at page 1-2. The Department of Revenue has regulations in place to define the rules governing the various possible special cases for computation of the tax credit. There has been some confusion about these regulations — DOR recently considered repealing them as defunct, unused in 35 years, but the regulations remain in force.

Current year effects

- Most estimates put the excess revenue for Fiscal 2022 at approximately $3 billion. See, for example, this publication from the Mass Taxpayers Foundation.

- State income tax revenues for fiscal 2022 are estimated at approximately $21 billion. So the resulting credit for taxpayers is going to be a little under 15% of their prior year’s taxes. For a taxpayer with $100,000 in taxable income paying $5,000 in taxes, the credit will be approximately $750 on the April 2023 state tax filing.

- Overall, while the tax credit is proportional to income, it will benefit higher income taxpayers disproportionately because higher income taxpayers pay more of their total taxes in the form of income taxes.

This law is frustrating. It’s like a Republican dirty trick. Of course when this was originally passed without context voters knee-jerk response was cut taxes. Money for schools? For housing or transportation? Public health? So lower middle class and middle class people get token amounts while top earners practically get endowments. Talk about trickle down. Housing, transportation, and public schools are not their concern,

When it comes to taxes, Will is all in.

He’s never seen a tax or tax override he doesn’t like.

His support for the “Millionaires Tax” referendum question is just because he supports a “graduated

income tax” for Massachusetts.

But he knows that voters have rejected it every time it has been on the ballot.

So Will has decided to conduct class warfare by piggy-backing on many people’s hatred of those who earn more than a million dollars. Will doesn’t like them either unless they donate to his unnecessary campaign chest.

In actual fact, Will has always supported a graduated income tax. In the future the million dollar limit will be reduced if Will has anything to say about it.

Of course, supposedly the tax revenue will be used “for the children.”

Will thinks you’ll like that part. It sounds so humane.