This post was written by Tom Phillips, our summer legislative intern. I am grateful for his work in this area. The issue of toxic environmental hazards — plastics, pesticides, PFAS, and chemicals — is becoming more and more important to me.

Why are pollinators important?

Pollinators play a crucial role in agricultural and natural systems. It is estimated that approximately 78% of all flowering plants in temperate areas depend on animal pollinators. The USDA has estimated that pollinator-dependent crops throughout the U.S. add approximately $10 billion in value to the economy each year, and the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) has stated that over 45% of Massachusetts’ agricultural commodities depend on pollinator species. Furthermore, insect pollinators are prey for many larger animal species. For example, approximately 80% of birds in the U.S. depend on insects like moths and butterflies for food.

What pollinators are in Massachusetts?

Bees are one of the major pollinators in Massachusetts. New England alone hosts over 350 species of native and introduced bees, such as honey bees (Apis mellifera), bumblebees (Bombus spp.), sweat bees (Agapostemon spp.), and eastern carpenter bees (Xylocopa virginica). Butterflies and moths also play an important role in pollination, with over 100 species found in New England. Many of these bee, moth, and butterfly species rely solely on one or few plant species for feeding and reproduction.

Threats to pollinators

Pollinator diversity and abundance has declined globally over the last few decades. The United Nations warns that 40% of invertebrate pollinators worldwide are currently threatened with extinction. This trend has been observed in Massachusetts as well. For example, a 2010 study from UMass Amherst reported that pollinator diversity in Massachusetts cranberry bogs declined dramatically between 1990 and 2009.

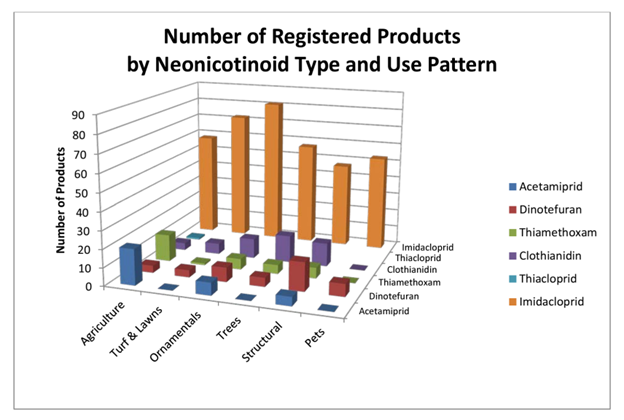

Pesticide use is thought to be a major cause of global pollinator decline. Scientists and advocates assert that pesticide products containing neonicotinoids, or “neonics,” pose an especially great threat to pollinators. Neonics are a family of pesticides that kills insects and other arthropods by disrupting the functioning of their central nervous system. At nonlethal doses, neonics can impact insects by altering behaviors that are essential for survival such as creating nests and escaping from predators. There are eight different chemicals in the neonicotinoid family: Acetamiprid, Clothianidin, Dinotefuran, Imidacloprid, Nitenpyram, Nithiazine, Thiacloprid, and Thiamethoxam. In 2021, MDAR stated that there were over 350 pesticide products in MA that contained neonics, with the highest number of these products designed for ornamental plants, turf, trees, and agricultural systems (Figure 1).

The impacts of neonics on pollinators are well documented. In a review published in 2020, it was found that over 90% of scientific literature on this subject from after 2009 gave evidence that neonics have potentially harmful chronic impacts on pollinators such as impaired brood development, colony collapse disorder, cognitive disruption, and abnormal foraging. Furthermore, in a 2017 study, it was found that very small oral doses of one particular neonicotinoid called imidacloprid were adequate to kill pollinators, with queen bumblebees dying after ingesting a 1 ppb (parts per billion) dose of the chemical. This finding is notable due to the high prevalence of neonics in U.S. ecosystems. In a 2016 paper, for example, it was found that over 70% of pollen and honey samples collected from Massachusetts beehives in 2013 contained at least one kind of neonic, with especially high concentrations found in the counties of Worcester, Hampshire, Essex, and Suffolk. The 2018 UMass Hobby Beekeeper Health Survey also found high amounts of neonics in Massachusetts hives, with 33% of all samples containing at least trace amounts of neonics. However, the USDA-APHIS Honey Bee Health Survey detected a considerably lower prevalence of neonics from sampled nests.

In a study of honeybees, imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam were shown to be the most acutely toxic chemicals in the neonic family, while acetamiprid and thiacloprid were considerably less toxic than the other chemicals. This is noteworthy due to the fact that these three chemicals, especially imidacloprid, have been the most widely used neonics in Massachusetts (Figure 1).

Actions being taken to limit the use of neonics

Over the last few years, advocates and policymakers in Massachusetts have pushed for legislation to expand restrictions on neonic use. In 2019, Representative Carolyn Dykema presented a bill entitled “An Act to Protect Massachusetts Pollinators,” which restricted the purchasing and selling of neonics by individuals who lack proper certification. Although this bill was not enacted, Representative Dykema was successful in obtaining a $100,000 budget appropriation that required the Massachusetts government to conduct a literature review evaluating evidence for the negative impacts of neonics on pollinators. The literature review found that 42 of 43 studies investigating this subject supported the conclusion that neonic exposure impacts pollinators. In response to this finding, the Massachusetts Pesticide Board Subcommittee voted in 2021 to change the classification of certain products containing neonics from “general use” to “state restricted use.” This change came into effect on July 1, 2022.

This new restriction dictates that un-certified people are no longer able to purchase neonic products that are designed for turfgrass, trees, golf courses, residential gardens, and similar uses. This restriction does not apply to neonic products designed for agricultural systems (e.g. greenhouses, crop fields, etc.), structures (e.g. wood structures that could be infested with termites), or for bloodsucking pests like fleas, ticks, mites, and bedbugs. It is still possible to obtain restricted neonic products, but people must have special certifications. Advocates mention that the Subcommittee neglected to require that licensed applicators inform clients of the potential dangers of applying neonics on their property. Furthermore, they note how the Subcommittee did not update the pesticide applicator training curriculum to include descriptions of the risks neonics pose to pollinators.

As with all pesticides, Massachusetts regulates neonics under the Massachusetts Pesticide Control Act (MPCA, Chapter 132B of the Massachusetts General Laws). This gives regulatory power to MDAR. Within MDAR is the Pesticide Program, which regulates pesticides in MA, serves as support staff for the Pesticide Board and Pesticide Board Subcommittee, and carries out the examining, licensing, and certification of pesticide applicators.

As of May 2024, eleven states have legislatively restricted neonic use. These include California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington State. Massachusetts is not included in this list because it implemented neonic restrictions through regulatory changes rather than by creating new legislation. It is difficult to compare the neonic restrictions of an individual state to the restrictions found in other states, because every region of the U.S. has different amounts of agricultural production and contrasting environmental features. However, one commonality between all the states is that none have completely banned neonics, as the E.U. did in 2018 for imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam. Regardless, certain states have dramatically limited the allowable uses of neonics, and many are considering further action to limit these chemicals, including highly agricultural states such as Illinois.

Areas for future inquiry

Many questions still remain regarding pollinator health in Massachusetts. Firstly, it is unclear whether pollinator abundance or diversity has increased in the Commonwealth since the neonic restriction came into effect. Additionally, it is unclear whether the restriction has markedly reduced the annual tonnage of neonic products used in Massachusetts. Data on sales of neonic products and their usage over time is not readily available; it is therefore hard to discern the impact restricting access has had. Potential actions this office could take in the future regarding this subject include: 1.) promoting legislation to fund a research project comparing current environmental neonic concentrations to neonic concentrations found in the environment before the restriction came into effect (perhaps borrowing data from Lu et al. 2016 or the 2018 UMass Hobby Beekeeper Health Survey), and 2.) promoting legislation that requires licensed applicators to inform clients of the dangers posed by neonic pesticides. It should be noted that after Rep. Dykema’s departure from the House, her 2019 pollinator bill was reintroduced to the House floor by Representative James Arena-DeRosa. The last action taken on it was in spring 2023 when it accompanied a study order.

More pollinator resources for Massachusetts residents

The state and federal governments have a number of grant programs for Massachusetts residents and communities who want to help restore diverse pollinator habitats. As mentioned earlier in this post, many pollinators feed and reproduce on a narrow range of plant species, so diverse plant communities are required to protect these insects.

State resources

MassWildlife Habitat Management Grant Program

Provides funding for the improvement of public access to outdoor recreation and the improvement of wildlife habitat to private and municipal owners of protected lands.

Land and Recreation Grants & Loans

Includes several programs that assist municipalities and nonprofits with projects such as restoration of outdoor recreation areas (e.g., trails and parks) and protection of public drinking water supplies.

Federal programming

Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP)

Provides cost-share funding for agricultural producers and forest landowners to improve environmental quality on private property.

In addition to offering these programs, the state and federal government offer many online resources that citizens can use to learn more about growing their own pollinator gardens:

Thanks, Will for the useful update.

I hope the MA Pesticide Board Subcommittee will make users aware of the continuing danger of applying neonics, and the threat that this continues to pose to our own health as well as that of pollinators..

This was a very helpful post… and frustrating… and scary. Thank you. We need to be able to get effective legislation passed! (On this issue and many others.)

This is a great overview of the state of science regarding neonicotinoids and pollinators. When Friends of Bees was first looking into this ten years ago, it was difficult to find any research that wasn’t mealy mouthed about its conclusions. I’m impressed to see your literature review showing a preponderance of evidence that neonics definitely harm bees and other pollinators. Thank you also for mentioning my favorite bee, the beautiful metallic green Agapostemon!

This is very helpful. What we really need is a complete ban on neonics in the state.