Overview and a Question

Early next year, the legislature will likely continue efforts to address the rising dysfunction, disability and death from opioid drug abuse. The Senate passed a bill this fall which is under consideration by the House. The Governor has also filed legislation and the House will likely have a bill of its own. Hopefully, we will be able to take the best elements of those bills to craft a final package. Meanwhile, the legislature and the administration are addressing many dimensions of the problem through other legislative vehicles and existing executive powers.

Focusing first on addiction to prescription pain killers, I wanted to pull statistics together and to get your local perceptions on the issue. You can wade through the numbers below, but I’ll offer my summary observations here:

- We face three intertwined problems:

- Casual, episodic youth abuse of pain killers with potentially tragic consequences. Thrill-seeking kids now have easy access to potentially fatal substances.

- Opioid/heroin addiction of young people, whether through a surgical or injury experience or, perhaps more commonly, just through continued risky abuse in a detrimental peer group.

- Older individuals with chronic conditions who may use or abuse pain relievers prescribed to them and perhaps make fatal mistakes using them in combination with other drugs like alcohol and benzodiazepines.

- An additional category of opioid users is cancer patients in hospice settings, where the only real issue is to protect them from pain.

- The problem of episodic youth abuse may be peaking and turning down as awareness builds as to the risks of pills.

- The problem of addiction and overdose among young adults is at its highest level ever and may not have peaked. The harms associated with addiction have been multiplied by the introduction of fentanyl into the illicit markets.

- There is a lot of evidence that doctors are getting the balance between pain control and addiction control wrong and letting too many pills out into the environment, but there are two sides to that story.

Based on what you are seeing and hearing yourself, are doctors you know getting the balance wrong and making pain medication too readily available? If they are getting the balance wrong, there is a second and distinct question: do you feel that the legislature should pass new laws regulating the decisions that doctors make with patients? I’m most interested in personal experiences, but also very interested in any reliable data sources that I should add to the collection below.

You can comment at the end of the article: Feel free to comment without using your full name if you prefer to remain anonymous. I’d very much welcome comments from physicians and other health care professionals.

Opioid Overdose Statistics

Recent data from the Center for Disease Control show that:

- In 2014, more people died in the United States from drug overdoses than in any previous recorded year.

- 47,055 died of drug overdoses — while only approximately 30,000 died in motor vehicle crashes.

- The national age-adjusted rate of drug overdose death more than doubled from 2000 to 2014 — from 6.2 per 100,000 people to 14.7 per 1000 people.

- The age-adjusted death rate in Massachusetts, 19.0 deaths per 100,000, was well above the national average.

- Opioid drugs — drugs that are derived from or act in the same way as opium, for example, heroin, fentanyl and oxycontin — were known to be involved in 61% of overdose deaths.

The breakdown underneath the national totals in the CDC report is as follows:

- The age group with the highest drug overdose rate is persons 45-54 years old, with 28.2 deaths per 100,000. Drug poisonings and suicides are driving an overall rise in mid-life mortality among middle-aged white non-Hispanic men and women (after decades of declining death rates).

- Youth aged 15-24 have a death rate that is considerably lower — 8.6 deaths per 100,000.

- People over 25 accounted for over 90% of the deaths.

- Men have a higher death rate than women — 18.3 vs. 11.1.

- Non-Hispanic whites have a death rate (19.0) that is much greater than the rates for Hispanics (6.7) and non-Hispanic Blacks (10.5).

The CDC notes that:

The 2014 data demonstrate that the United States’ opioid overdose epidemic includes two distinct but interrelated trends: a 15-year increase in overdose deaths involving prescription opioid pain relievers and a recent surge in illicit opioid overdose deaths, driven largely by heroin. . . . [I]llicit fentanyl is often combined with heroin or sold as heroin. Illicit fentanyl might be contributing to recent increases in drug overdose deaths involving heroin. Therefore, increases in illicit fentanyl-associated deaths might represent an emerging and troubling feature of the rise in illicit opioid overdoses that has been driven by heroin.

In Massachusetts, unintentional opioid overdose deaths have occurred in almost every community over the past three years. Opioid overdose deaths, 80% of which are unintentional, have grown by a factor of 8 over the past 25 years. Unintentional opioid deaths roughly doubled from 2000 to 2013. The demographics of opioid deaths in Massachusetts are similar to the national demographics — tilted to towards people who are middle-aged, white and male and more prevalent than motor vehicle deaths — see Tables 18 and 19 in this death analysis from the Department of Public Health. Local anecdotes that I hear as a legislator also point towards a heavy role for fentanyl and fentanyl/heroin combinations in the recent spike in overdose deaths.

Surveys of Substance Use Prevalence

According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the number of people admitting past-month use of pain-relievers has remained fairly stable for the last decade, bouncing around 2% of respondents (actually dropping slightly in 2013). The rate of admitted past-month heroin use was lower, 0.3% among young adults in 2013, but the rate of heroin use use appears to be rising to levels perhaps twice those reported early in the century.

The count of heroin users reported in the survey is a soft guess, likely a significant underestimate — typically survey methods are less likely to reach people whose lives have become chaotic. Alternative measurements of cocaine use prevalence suggested rates far above those detected by surveys in a study I did in the 90s. However, the divergence in trends (between prescription drugs and heroin) is meaningful and consistent with the divergence in trends in the death statistics.

While deaths from prescription drug overdose are higher among middle-aged adults than among young adults, more young adults (18 to 25) admit past month non-medical use of “psychotherapeutics” — the category that includes pain relievers — than older adults: 4.8% as compared to 2.1%. But the young adult rate was lower in 2013 than the rates from 2002 to 2010.

The number of first time users of non-medical psychotherapeutics dropped significantly in 2013 to 1.539 million — the peak year in the past decade was 2003 with 2.456 million initiations. The rate of initiation is a leading indicator, so this drop is encouraging. The 2013 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey, administered confidentially in schools, shows drug use flat to down in most categories. However, non-medical use of prescription drugs is still second only to marijuana as measured by life-time experience among high school students (41% vs. 13% vs. single digits for other kinds of drugs).

Also perhaps encouraging are the leveling-off in the rate of persons meeting criteria for dependence on or abuse of pain relievers — see the Household Survey at Figure 7.3 — and the drop in illicit drug dependence among youths aged 12 to 17 (Figure 7.5). This coincides with an increase in the rate of people receiving treatment for pain relievers (Figure 7.9).

One way of reading these data is that, overall, fewer people are initiating abuse of pain relievers and the trend may be positive, but there is an increasingly visible sub-population that is continuing to use, turning to heroin, feeling the need for treatment and overdosing on fentanyl-laced street drugs.

Health Care Events

Treatment data are hard to interpret because drug treatment program admissions reflect both need and availability. Availability may be more stable than need, so stability in treatment admissions may be as much related to limited availability as to need. With that caveat, treatment statistics from the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Abuse Services, show the following:

- Overall admissions were stable at about 100,000 per year from 2005 through 2014.

- In the same period, heroin admissions rose as a share of overall admissions, from 38.2% to 53.1%, while alcohol and cocaine admissions fell.

- Admissions for opioids other than heroin peaked at 10.9% in 2011 and dropped backed to their 2005 level of under 6% by 2014.

- Youth admissions (under 18) trended slightly down from 2004 to 2012. For most youth (72.2%) marijuana or alcohol was the primary substance of abuse, but 14.8% reported having used heroin in the past year and 33.2% reported having used other opioids in the past year.

- Admissions for older adults (over 55) trended distinctly upward from 2003 to 2012. Alcohol was the primary drug of abuse in 71.4% of the admissions, but 17% were admitted for heroin abuse and 9.2% had used other opiates in the past year.

Emergency room admissions are less constrained by supply and do show increases in the period from 2004 to 2011. Boston-area emergency rooms report to the federal Drug Abuse Warning Network. Emergency room visits in the Boston-Cambridge-Quincy Metropolitan Statistical Area show the following trends:

- Overall, emergency room visits for substance abuse rose 41% from 2004 to 2011 — 35% among persons 21 to 24, 97% among persons 45 to 54.

- The total number of emergency room visits was estimated at 51,845 in 2011 or roughly 1 for every 100 persons in the area (although many visitors may have repeated, so the true share of people with a visit to the emergency room for substance abuse is probably lower).

- Mentions of cocaine use (12,562) were only slightly below heroin mentions (14,057) in 2011; both categories trended upwards from 2004 — cocaine mentions by 34%, heroin mentions by 37%. The 2011 data do not capture the recent spike that has been so much in the news.

- Mentions of opiates/opioids were up 68% in the period, reaching 9,354 in 2011.

- Benzodiazepines (anti-anxiety drugs like valium) were also up 66%, reaching 8,725 in 2011, close behind the pain relievers.

This last finding highlights the risks of polysubstance abuse. Rhode Island’s Strategic Plan on Addiction and Overdose examined the concurrent use of substances resulting in overdose deaths, finding that benzodiazepines were frequently present together with cocaine, heroin and/or fentanyl.

Prescription Drugs

There is little debate as to whether increased prescriptions by doctors of opioids for pain have contributed to addiction and overdoses. I have heard countless stories of people who have received prescriptions for large quantities of narcotics after relatively minor procedures. They are then faced with the question of how to dispose of them. I have a friend whose child got in trouble for bringing to school pills left over from a surgical procedure and attempting to sell them.

In her testimony to Congress on May 14, 2014, the head of National Institute on Drug Abuse, said:

Several factors are likely to have contributed to the severity of the current prescription drug abuse problem. They include drastic increases in the number of prescriptions written and dispensed, greater social acceptability for using medications for different purposes, and aggressive marketing by pharmaceutical companies. These factors together have helped create the broad “environmental availability” of prescription medications in general and opioid analgesics in particular.

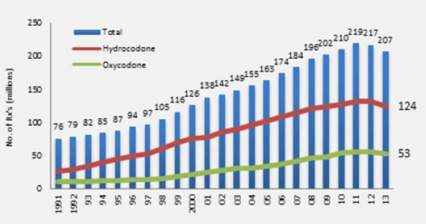

The figure below, taken from the same testimony shows opioid prescriptions dispensed by US retail pharmacies almost tripling from 1991 to 2011, although dropping slightly over the last year or two.

To put these quantities in perspective, in 2010 enough opioid pain relievers were sold in the United States to “medicate every American adult with a typical dose of 5 mg of hydrocodone every 4 hours for 1 month.” Put that another way, enough pain relievers were sold to keep 1 in 12 adults medicated on a year round basis. Geographic and demographic variations in prescription rates correlate roughly with overdose death rates.

The Governor’s Working Group on opioids cited a telling statistic from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2013:

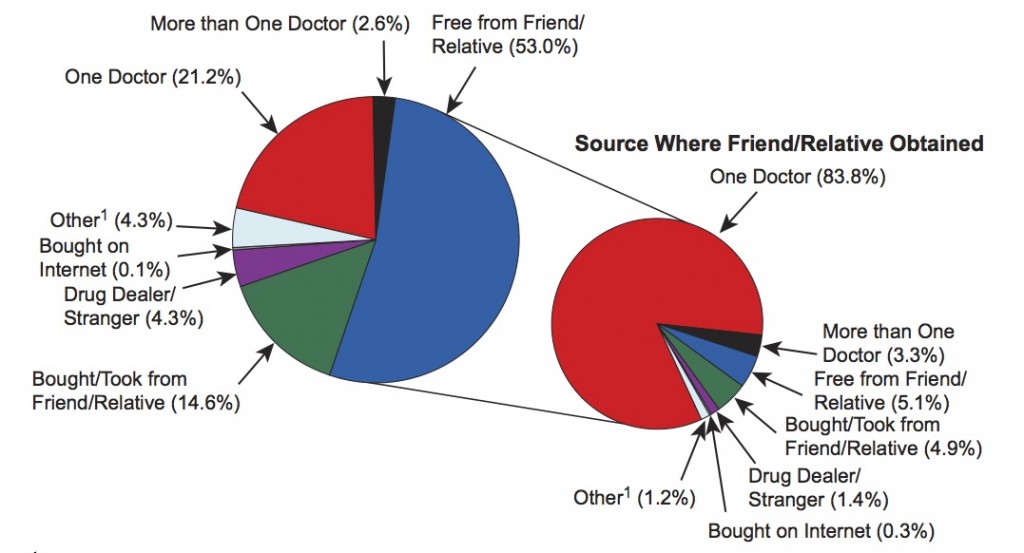

Source Where Pain Relievers Were Obtained for Most Recent Nonmedical Use among Past Year Users Aged 12 or Older: 2012-2013

This chart shows that very few people using pain relievers non-medically got them from strangers or dealers (only 4.3%). Some got them directly from doctors but most got them from friends or relatives who, in turn, in 83.8% of cases, got them from one prescribing doctor. These survey results apply to the whole universe of people who have used opioids in the past year and therefore includes many who use is only casual. Another study reached a different conclusion as to the sources of drugs for people actually diagnosed with opioid abuse or dependence: 79.9% had an opioid prescription of their own prior to their first abuse diagnosis. But either way, the source of abused opioids is prescriptions.

An equally telling statistic from the National Survey is that among the 2.8 million people who used drugs illicitly for the first time in 2013, over 20% started with nonmedical use of prescription drugs, 12.5% with pain relievers — marijuana is the most common first drug, but many people go straight to pills. A further stunning statistic consistent with a perception that there are just too many pills out there accessible to kids — not only opioids, but other abusable psychoactive drugs — was that 12 and 13 year-olds were more likely to admit using pills nonmedically in the past month (1.3%) than marijuana (1.0%) — Figure 2.8 in the National Survey. Another study that the Governor’s working group cited indicates that “[A]dolescent males who participate in sports may have greater access to opioid medication, putting them at greater risk to misuse these controlled substances.”

A CDC analysis in 2012 showed that how widely prescription rates vary across the states, tending to suggest differing approaches to main management. Massachusetts compares as follows:

- Low in its overall prescription rates for opioid pain relievers, ranking 41st in prescriptions compared to populations.

- Low in prescribing high dose pain relievers, ranking 41st.

- High in long-acting, extended-relief opioids like Oxycontin, ranking 8th among the states.

- High in benzodiazepines, ranking 9th among the states.

That CDC analysis concludes:

Factors accounting for the regional variation are unknown. Such wide variations are unlikely to be attributable to underlying differences in the health status of the population. High rates indicate the need to identify prescribing practices that might not appropriately balance pain relief and patient safety.

The Pain Control Movement

As clear as it is that pain medications are a precipitating factor for the surge in addiction, there is also a powerful movement to control pain better. In fact, in section 4305 of the landmark Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Congress ordered the Department of Health and Human Services to convene a conference with the following purposes — to:

(A) increase the recognition of pain as a significant public health problem in the United States;

(B) evaluate the adequacy of assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and management of acute and chronic pain in the general population, and in identified racial, ethnic, gender, age, and other demographic groups that may be disproportionately affected by inadequacies in the assess-

ment, diagnosis, treatment, and management of pain;

(C) identify barriers to appropriate pain care;

(D) establish an agenda for action in both the public and private sectors that will reduce such barriers and significantly improve the state of pain care research, education, and clinical care in the United States.

The Institute of Medicine convened a distinguished panel in response to this order. Their report brief dated June 2011, defines pain as a problem affecting 100 million people in the United States and costing $635 billion per year. It uses the same kind of ambitious language used by groups seeking to address drug abuse use, but focuses on pain as the problem:

Pain represents a national challenge. A cultural transformation is necessary to better prevent, assess, treat, and understand pain of all types. Government agencies, healthcare providers, healthcare professional associations, educators, and public and private funders of health care should take the lead in this transformation. Patient advocacy groups also should engage their diverse constituencies.

In comments delivered to the panel, pain patients lamented their treatment as criminals and physicians prescribing opioids complained of unfair scrutiny. The federal panel’s full report spoke of access to opioids for pain as a human right.

A reasonable degree of access to pain medication—such as the stepped approach of the World Health Organization’s Pain Relief Ladder for cancer—has been considered a human right under international law since the 1961 adoption of the U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Lohman et al., 2010; WHO, 2011). Similarly, countries are expected to provide appropriate access to pain management, including opioid medications, under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, which guarantees “the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” (citation omitted).

The full report does recognize the “conundrum of opioids” as an “underlying principle”, but views it as a manageable problem:

The committee recognizes the serious problem of diversion and abuse of opioid drugs, as well as questions about their long- term usefulness. However, the committee believes that when opioids are used as prescribed and appropriately monitored, they can be safe and effective, especially for acute, postoperative, and procedural pain, as well as for patients near the end of life who desire more pain relief.

The committee viewed opiate abuse as a nuance of pain treatment. Even though the committee devotes a full chapter to pain care and does touch on the issues of diversion and abuse, its recommendations related to pain care focus entirely on removing barriers to treatment, not on reducing abuse. Its overall recommendations seek to encourage greater awareness and treatment of pain as a public health problem. The Massachusetts Pain Initiative is a local organization devoted to those goals which has expressed reservations about both the Senate’s bill and the Governor’s bill that would restrict access to opioids. For more statements and studies on the pain issue, see Drug War Facts.

Consistent with a national effort to treat pain better, the federal government’s hospital care quality survey includes pain management as a metric. Consumers can compare hospitals on a federal website based on the what percentage of patients reported that “their pain was ‘Always’ well controlled”. The pain questions also factor into a federal 1 to 5 star rating system for the patient experience of care in hospitals. In a recent conversation with a hospital administrator, I heard frustration that this system pushes hospitals to use powerful pain medication to get “smiley faces”.

The Governor’s Opioid Working Group, in its June 2015 report, included training for “all practitioners” as to “addiction and safe prescribing practices” as a key strategy. The Massachusetts Medical Society promptly, in August 2015, updated its guidelines for Opioid Therapy and Physician Communication. In October 2015, the Board of Registration in Medicine incorporated these guidelines into new standards of care motivated by the Working Group’s findings.

Summary and Question

Clearly, physicians who are called upon to treat pain face powerful conflicting goals and incentives. Pain is a real problem and addiction is a real problem. Based on what you are seeing and hearing yourself, are doctors getting the balance wrong and making pain medication too readily available? If they are getting the balance wrong, there is a second and distinct question: do you feel that the legislature should pass new laws regulating the decisions that doctors make with patients? I’m most interested in personal experiences, but also very interested in any reliable data sources that I should add to the collection above.

Feel free to comment without using your full name if you prefer to remain anonymous. I’d very much welcome comments from physicians and other health care professionals.

Responses to comments, December 24, 2015

Thanks to all who have weighed in so far — I have read the comments carefully. Here is what I heard:

- A number of people offered examples of receiving much more pain relievers than they needed after simple procedures. It seems clear that there has been a pattern of this. While the need for pain medication is very real in some cases, the pain movement did manage to overshoot, especially when combined with the pressures of satisfaction rating systems and pharmaceutical marketing. The answer to the first question about whether doctors have been getting the balance wrong is “yes, in many instances, but they may be making an adjustment.”

- Other people offered examples of having a hard time getting the pain medications that they legitimately need. It seems clear that this also happens and may happen more in the future. And I hear the point that managing pain and medication can be very complicated and that the idea of “balance” is an oversimplification. It is much harder to judge how often too much medication has been offered in chronic pain cases. This ties broadly to the issue of over treatment generally, very hard to judge — doctors have tools and they may like to use them too much, but those tools can do great good.

- Overall, in this thread of comments, the answer to the second question about whether we should pass new prescription laws is much less clear, but tilts towards “no, don’t interfere in the doctor patient relationship.” I hear some mistrust of doctors (too influenced by big pharma), but more mistrust of government — too likely to put in place clumsy new rules that will help in some cases, but hurt in others.

My sense of the issue is that doctors are under a lot of pressure. Clearly, the Massachusetts Medical Society is responding aggressively with education measures. All too often in the history of drug regulation, by the time we pass new laws, society has already solved the problem in other ways.

Given the current severity of the epidemic and the elevation of public concern, we in the legislature inevitably will pull every lever we can reach, including additional regulation of prescriptions. That is what we always do, for better or for worse — we respond. My goal will be to make sure that the voices of physicians and patients are heard, along with the voices of those who have lost loved ones to addiction, and that the legislation is framed as sensitively as possible to both groups of concerns.

Legislative Progress Update, January 11, 2015

The House is bringing to the floor an updated substance abuse bill. The approach in this bill is very moderate — essentially encouraging doctors to limit prescriptions to seven days, but allowing them latitude to go further if they record the reasons behind their professional judgment to do so. This seems likely a sensitive and realistic approach.

Section 19D. (a) When issuing a prescription for an opiate to an adult patient for the first time, a practitioner shall not issue a prescription for more than a 7-day supply. A practitioner shall not issue an opiate prescription to a minor for more than a 7-day supply at any time and shall discuss with the parent or guardian the risks associated with opiate use.

(b) Notwithstanding subsection (a), if in the professional medical judgment of a practitioner more than a 7-day supply of an opiate is required to stabilize the patient’s emergency medical condition, or the opiate is prescribed for chronic pain management, pain associated with a cancer diagnoses or for palliative care, then the practitioner may issue a prescription for the quantity needed to stabilize the patient’s condition. The condition triggering prescription of an opiate for more than a 7-day supply shall be documented in the patient’s medical record and the practitioner shall indicate that a non-opiate alternative was not appropriate to address the emergency medical condition.

The Senate Chair of the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Committee has commented favorably on the proposal. This more moderate approach is likely to be the way we end up going, but there will be several additional steps of this process before an approach is finalized.

The head of the Massachusetts Medical Society was quoted in the State House News on January 11 as follows:

“I think it’s fair to say we recognize there are too many opioids circulating in the community at large. One of the ways to address that is to take a look at the volume of prescriptions at the front end. We think that looking at a seven-day initial limit as was mentioned in this bill is a reasonable compromise.”

Additional thoughts welcome!