A constituent recently contacted Senator Brownsberger’s office regarding Amazon’s plan to use drones to make deliveries to consumers. The constituent raised some concerns about the safety of drone usage, and asked us about the process through which companies like Amazon are able to gain permission to use drones in the United States and within various municipalities and states. I found that state and local governments are fairly limited in their ability to regulate commercial drone usage, as airspace and aircraft in under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Here’s more of what I found on the regulation of autonomous drone delivery:

Autonomous Drone Delivery

In June 2019, Amazon unveiled its latest drone design, a fully electric device that can fly up to 15 miles and deliver packages under 5 pounds in less than 30 minutes. These drones are autonomous and use artificial intelligence (AI) to identify objects in its vicinity and chart a clear flight path. This AI technology enables the drone to react to changes in its surroundings in real time. Using proprietary sensors and algorithms, this drone can detect static and moving objects and alter its flight path to accommodate them, like how a human reacts to other people walking along the sidewalk with them, or approaching cars as they cross the street. This drone is even able to detect items as thin as a clothesline, and move around it. This drone can do vertical takeoffs and landings, like a helicopter, and also navigate horizontally, like an airplane, and can transition between these two modes seamlessly. The drone can move with six degrees of freedom, meaning it can not only move horizontally and vertically along the x,y and z axes, it can also rotate between those axes. To make deliveries, the drone requires a small area around the delivery location that is clear of people, animals, objects and obstacles in order to land.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_degrees_of_freedom

Autonomous drone delivery is being hailed by some as an innovation that will greatly improve people’s lives. As it is a new technology, however, there are concerns about how autonomous drone delivery will affect people and wildlife. Autonomous drone delivery is not yet used on a large scale by any company in the United States, so concerns around the practice are largely theoretical. As the technology around autonomous drone delivery is evolving, so is the regulatory landscape that governs the usage of drones commercially.

Regulation on the Federal Level

Airspace and the usage of aircraft in the United States is regulated by the FAA. 49 U.S. Code §?40103 states “The United States Government has exclusive sovereignty of airspace in the United States” and “The administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration shall develop plans and policy for the use of navigable airspace,” meaning that only the national government can regulate airspace and aircraft. “Navigable airspace” is defined as “airspace above the minimum altitudes of flight…including airspace needed to ensure safety in take off and landing.”

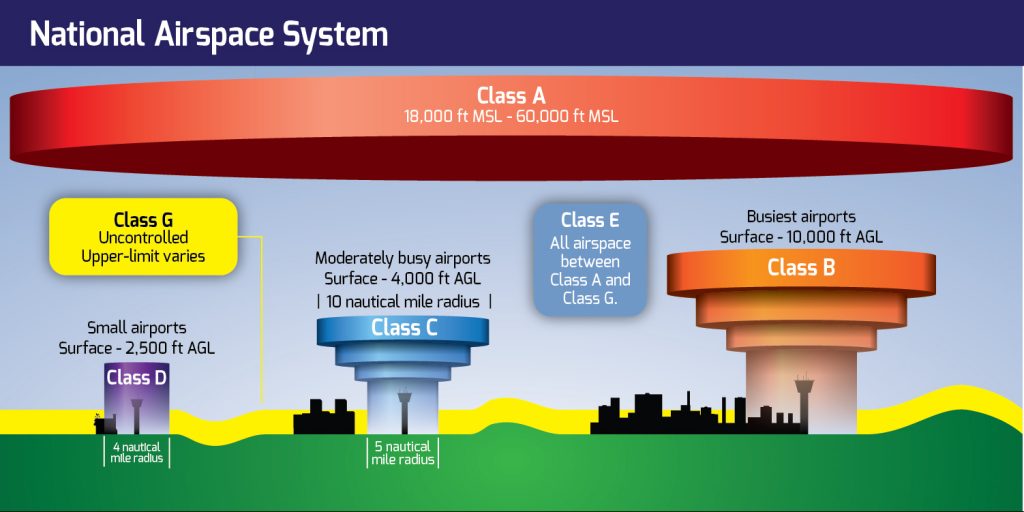

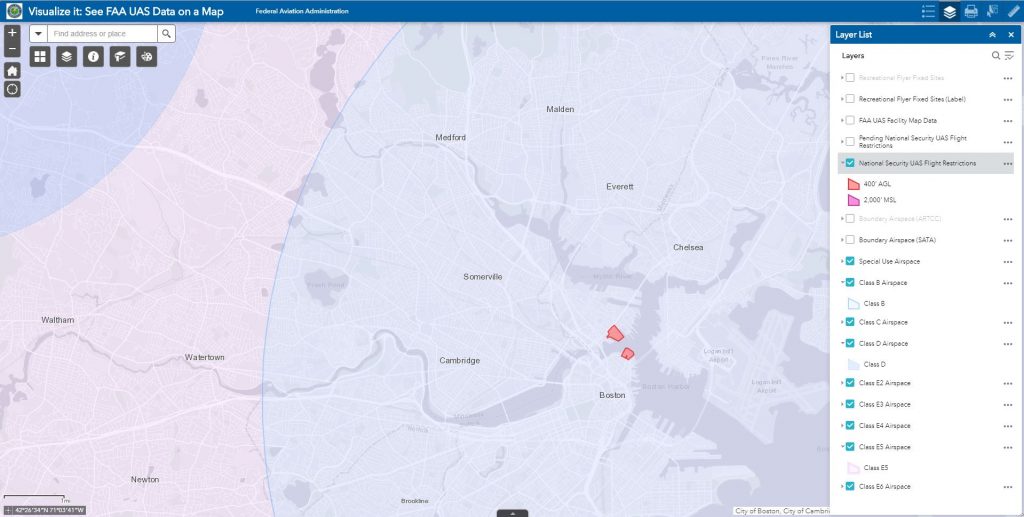

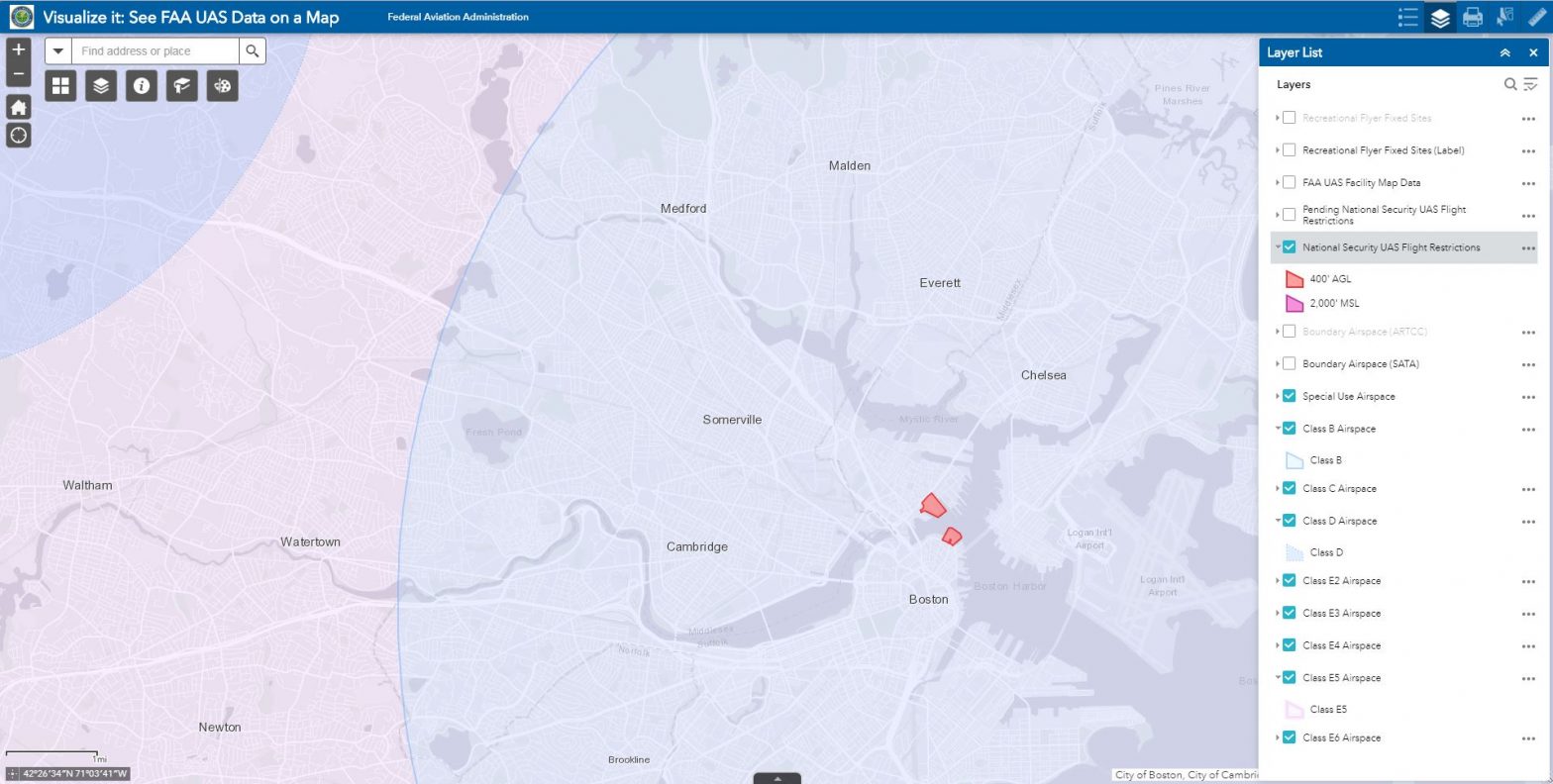

Airspace over the United States is divided into different classes, which determines what regulations cover the usage of that airspace. Drone delivery companies would have to ensure that their drones and drone operations comply with the regulations for every airspace class they fly within. The federal government also designates special use airspace, which is airspace that is governed by its own special set of regulations. Under the Aeronautics Information Manual, pilots are asked to keep their aircraft 2000 ft above the surface of National Parks, Monuments, Seashores, Lakeshores, Recreation Areas and Scenic Riverways administered by the National Park Service, National Wildlife Refuges, Big Game Refuges, Game Ranges and Wildlife Ranges administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Wilderness and Primitive areas administered by the U.S. Forest Service. As commercial drones must fly within 400ft of ground level, this effectively prohibits commercial drone usage in the airspace above those areas. There are also federal statutes prohibiting certain flight activities over specific U.S. Wildlife Refuges, Parks and Forest Service Areas. This link goes to a map that lets you see how different airspace is classed in different places by the FAA: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=9c2e4406710048e19806ebf6a06754ad

All of Senator Brownsberger’s district is controlled airspace.

To use drones in delivery, the drones and their operation must comply with or get exemptions to 14 CFR § 107, which outlines regulation of commercial drone usage, as well as obtain air carrier certification, which normally regulates charter aircraft use, such as using planes to deliver mail and to run routes not covered by commercial aircraft, and allows a company to make air deliveries across state lines and national borders and to carry mail. Some of the rules outlined in 14 CFR § 107 include:

- The drone must remain within the visual line of sight of the remote pilot in command and the person physically controlling the drone or a designated visual observer. Observing the drone through a camera does not satisfy this requirement. Also, at all times the remote pilot in command and the person physically controlling the drone must remain close enough to the drone while it is in flight, to be able to see the drone without any visual aids other than corrective lenses.

- No remote pilot in command or visual observer may serve in that capacity for more than one aircraft at a time

- The drone cannot be operated from a moving vehicle unless in a sparsely populated area, or in a moving aircraft.

- Drones may not fly over any persons not directly participating in the operation of the drone, may not fly under any covered structures or inside a covered stationary vehicle.

- The FAA definition of flight “over people”: The term “over” refers to the flight of the small unmanned aircraft directly over any part of a person. For example, a small UAS that hovers directly over a person’s head, shoulders, or extended arms or legs would be an operation over people. Similarly, if a person is lying down, for example at a beach, an operation over that person’s torso or toes would also constitute an operation over people. An operation during which a small UAS flies over any part of any person, regardless of the dwell time, if any, over the person, would be an operation over people.

- The FAA definition of people “directly participating”: The term “directly participating” refers to specific personnel that the remote pilot in command has deemed to be involved with the flight operation of the small unmanned aircraft. These include the remote pilot in command, the person manipulating the controls of the small UAS (if other than the remote pilot in command), and the visual observer. These personnel also include any person who is necessary for the safety of the small UAS flight operation. For example, if a small UAS operation employs a person whose duties are to maintain a perimeter to ensure that other people do not enter the area of operation, that person would be considered a direct participant in the flight operation of the small UAS.

The rules currently outlined in 14 CFR § 107 are written under the assumption that a person is controlling the drone, and does not consider the usage of autonomous drones. It would be impossible for Amazon, or any other drone delivery company, to make wide-scale consumer drone delivery make sense financially or logistically under the current rules, let alone operate autonomous drones commercially. The rules outlined in 14 CFR § 107 can be waived, however, if the applicant demonstrates that his or her operation can safely be conducted under the terms of a certificate of waiver. Amazon’s most recent drone model does not comply with 14 CFR § 107, and has not obtained any exemptions to 14 CFR § 107. Other autonomous drone delivery companies, like Wing and Flirtey, have obtained 14 CFR § 107 exemptions for their drones.

Only one company, Wing, which is owned by Alphabet, currently has regulatory approval to make autonomous commercial drone deliveries. Wing gained regulatory approval through the Integration Pilot Program, under which 10 projects undertaken by drone companies in partnership with local government authorities and state educational institutions can explore new drone usage ideas unencumbered by federal regulations, within the jurisdiction and oversight of their partner governments. While some of the other projects approved under the Integration Pilot Program involve autonomous drone usage, only Wing, in partnership with Virginia Tech, has been approved to make autonomous drone deliveries to consumers. While Wing is part of the Integration Pilot Program, they still had to obtain air carrier certification and exemptions to 14 CFR § 107 in order to make consumer deliveries. Wing is currently limited to making deliveries in the Southwest Virginia towns of Blacksburg and Christiansburg under the terms of their Integration Pilot Program project. Flirtey was also approved to make drone deliveries under the Integration Pilot Program, and is working towards delivering goods to consumers, but their approved project focuses on making medical deliveries, specifically delivering defibrillators to cardiac arrest patients.

https://www.cnn.com/videos/business/2019/04/09/wing-google-drone-delivery-australia-orig.cnn-business

State and Local Regulations

State and local governments can regulate drones through laws regarding land usage, privacy, law enforcement and other matters that are not regulated by the federal government. Examples of regulations local governments can pass regarding drones include: bans on landing/launching drones in their municipality, banning the usage of drones to spy on others, banning the usage of drones to harass people and prohibiting the attachment of weapons onto drones. How much autonomy state and local governments should have in regulating drone usage is an issue that is still being resolved, as aircraft often move between local jurisdictions, and having to navigate many different and conflicting sets of regulations would make it difficult for aircraft to operate. . The balance between local and federal government in regulating drone usage is one of the issues being explored by the FAA in the Integration Pilot Program.

Singer v. City of Newton, a recent Massachusetts District Court case, addressed local government autonomy in drone regulation. The city of Newton passed a drone ordinance in December 2016 stipulating that all drones used in the city must be registered with the city clerk’s office, drones may not fly in the airspace up to 400ft above ground level without property owner permission, and drones must remain within the visual line of sight of the operator at all times. Dr. Michael Singer sued the City of Newton, arguing that he could not comply with federal law and the city ordinance and still operate his drone, which he hoped to use as part of his medical practice, and that the city ordinance was preempted by federal law, making it invalid. This type of preemption, when local and federal laws conflict or when local law makes it difficult to implement federal law, is called “conflict preemption.” Due to the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution (Article VI Paragraph 2), if federal and local law conflict, federal law preempts the state law, meaning the federal law applies instead of the state law. Singer also claimed that the City of Newton’s ordinances were also “field preempted.” This notion of “field preemption” was established in Pennsylvania vs Nelson, which struck down a state law because it “touch[ed] a field in which the federal interest is so dominant that the federal system [must] be assumed to preclude enforcement of state laws on the same subject.” Thus, if a certain matter is field preempted, it would be considered to be under the exclusive authority of the state, and any state laws concerning or regulating that matter would be considered invalid.

The US District Court in the District of Massachusetts agreed that the City of Newton’s drone ordinance was conflict preempted, but not that it was field preempted. The District Court found that the requirement to register drones was conflicted preempted because FAA had shown a clear intent to be the exclusive authority on drone registration, and the local registration requirement would conflict with the FAA’s authority. As the FAA requires commercial drone users to fly within 400ft of ground level, the District Court found that the City of Newton’s requirement that drones obtain the permission of landowners in order to fly within the airspace 400ft above their property was conflict preempted because it “thwart[ed] not only the FAA’s objectives, but also those of Congress for the FAA to integrate drones into the national airspace.” The District Court also invalidated the City ordinance that required drones to remain in the visual line of sight of the operator, because “Congress has given the FAA the responsibility of regulating the use of airspace for aircraft navigation and to protect individuals and property on the ground,” and “the Ordinance limits the methods of piloting a drone beyond that which the FAA has already designated,” making it conflict preempted because Newton would be interfering with the FAA’s oversight.

Courts within the District of Massachusetts must now follow the precedent set in Singer v. Newton, meaning that Massachusetts local governments can regulate commercial drone usage, but laws regulating commercial drone registration, commercial drone piloting, navigable airspace and laws instituting commercial drone bans would be invalid due to conflict preemption. Following the District Court’s logic, it would be difficult for state governments to regulate commercial drone operation and safety without those regulations being struck down as conflict preempted.

One municipality in Massachusetts, the town of Barnstable, has a local ordinance regarding commercial drone usage. Banstable passed an ordinance prohibiting using, landing, operating or launching a drone, commercial or recreational, from or on land or waters associated with Barnstable Beaches without permission from the town manager. This ordinance does not conflict with the FAA’s “exclusive sovereignty” because it does not cover the airspace above Barnstable, only the land and waters, which are under the jurisdiction of the town of Barnstable. This ordinance has not been challenged in the courts.

Several bills are in the development process at the Massachusetts Legislature regarding drones, S.1446, H.3139 and H.1406. S.1446 regulates how government employees can use drones, and prohibits drones from being equipped with weapons. H.3139 would prohibit arming drones with weapons or anything that can fire a projectile that could cause harm, using a drone in a manner that would impede airport and aircraft operations,using a drone to inhibit first responders or law enforcement responding to an emergency, or using a drone to surveil an individual or their property. H.1406 would punish the weaponization of a drone, the usage of a drone to surveil an individual in a situation where they would have a reasonable expectation of privacy, and the usage of a drone to surveil a critical infrastructure facility without lawful authority.

Erica Hogan

Intern

Office of Senator William N. Brownsberger

In planning for the future, shouldn’t we consider the possibility

that commuting as we know it will become obsolete or vestigial?

Perhaps the daily migration of huge numbers of people will become

quite unnecessary; we may primarily move information and goods

rather than people. And maybe that will be much more energy efficient.