Capital funding for major maintenance of public housing was central in our recent housing bond bill. Similarly, stronger operating support for public housing has been a high priority in the last few annual budgets. This post documents the recent spending increases, puts them in context, and reviews other policy measures.

Public housing — background

By “public housing,” we mean housing owned and operated by a public entity; public housing is rented to people with limited incomes. (The distinct term “affordable housing” is usually used to refer to housing that is subsidized by public funds, but is owned and operated by a private entity.)

Most public housing in Massachusetts is administered by local authorities under the supervision of the state’s Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities. Legislation passed in 2014 substantially increased the state oversight role. The state provides housing authorities with capital maintenance funding and an operating subsidy to help lower rents.

MassNAHRO’s road map document for public housing offers the following basic statistics about public housing in Massachusetts:

- 242 Housing Authorities

- 43,000 units [approximately 1.4% of the 3 million housing units in Massachusetts]

- 70,000 residents [approximately 1% of the Massachusetts population of 7 million]

- 70% of residents are seniors

- $13 billion value of public housing facilities [approximately $300,000 per unit — replacement cost much greater]

- Only permanent housing available to people of extremely low income (<30% of area median income)

The table below lists the housing authorities and the number of public housing units in the four communities that I represent.

| Community | Housing Authority | Housing Authority Units | 2020 Census All Housing Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belmont | Belmont Housing Authority | 256 | 10,882 |

| Boston | Boston Housing Authority | ~10,000 | 301,702 |

| Cambridge | Cambridge Housing Authority (unit counts here) | 2,740 | 53,907 |

| Watertown | Watertown Housing Authority | 589 | 17,010 |

Planned spending increases

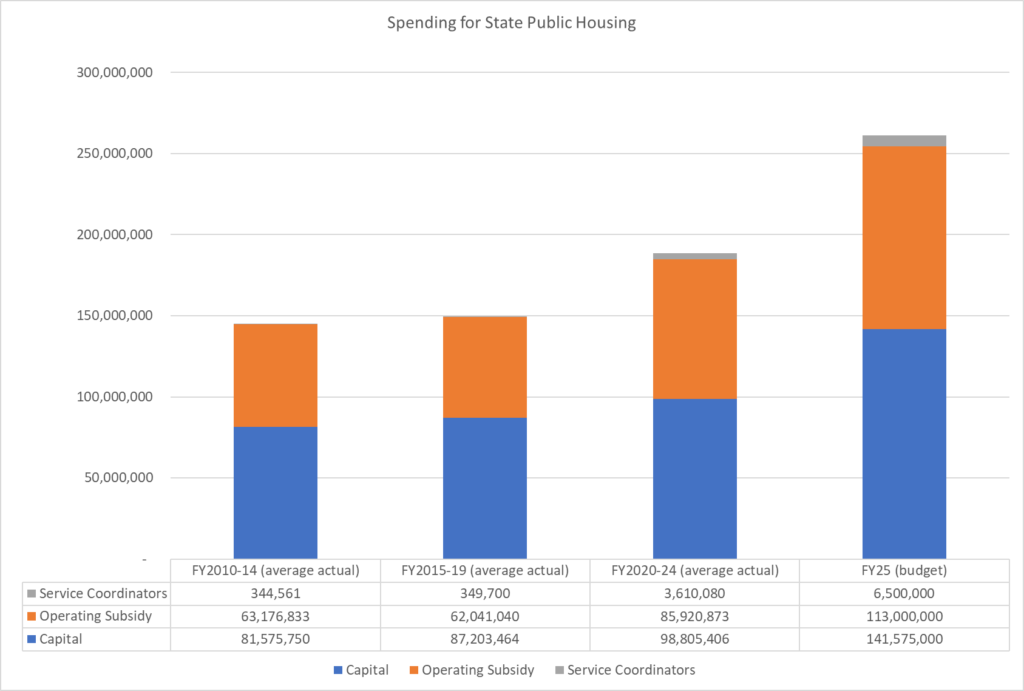

The chart below shows a consolidated view of the state’s operating subsidy and capital spending for public housing, comparing the average of actual annual spending in three previous 5 year periods to the FY25 budget.

- The operating subsidy is intended to cover the gap between rent roll and total operating costs; total operating costs include all annual costs of running the housing authority — not only routine maintenance, but all administration, utilities, etc.

- The capital spending supports larger maintenance projects. The FY25 amount for capital spending is based on the state’s capital spending plan. The relationship between our bond-funded capital authorizations and the somewhat smaller capital spending plan are explored in this previous post on housing capital spending and this previous post on constraints on capital spending.

- Note that the capital plan line item for public housing shown here focuses on maintenance, not expansion. Some expansion and redevelopment projects are contemplated through partnerships with developers; these projects may involve a mix of market, deed restricted affordable, and public housing units. Construction subsidies for these projects flow through a mix of other state and federal programs.

State Spending for Public Housing — capital and operating, FY2010 to FY2025

In addition to the items above which show the substantially increased state investments, public housing authorities benefitted from federal ARPA funds passed through the state. $150,000,000 was appropriated from ARPA funds to public housing maintenance by the Acts of 2021, Chapter 102, line item 1599-2024. As of August 25, 2024, only $48m of these funds had been disbursed (mostly in 2024), although more may have been committed. Whether through new or existing commitments, an additional $102m in ARPA funds are still to flow out for public housing maintenance over the next three years ending June 30, 2027. The ARPA fund appropriation language emphasizes infrastructure, in accordance with ARPA funding guidelines, and so may be more difficult to allocate than the flexible general maintenance capital budget.

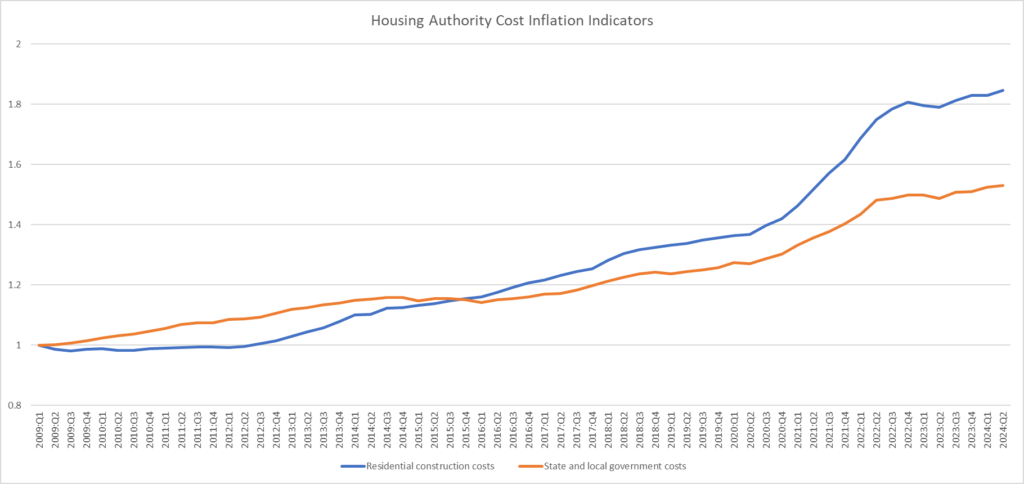

An important part of the challenge for public housing authorities has been inflation. Prices are often compared over time in one of two ways: (1) through the “consumer price index” prepared by the Bureau of Labor Statistics; (2) through “implicit price deflators” used by the Bureau of Economic Analysis to adjust gross national product estimates. For housing capital spending, the most relevant price indicator is the implicit price deflator for residential construction, which rose sharply through the COVID pandemic. For the operating subsidy and the service coordinator line items, the most relevant price indicator is the general price inflator for consumption expenditures and gross investment by state and local governments. The chart below compares the trends in those two price indicators.

Cost trends affecting housing authorities (national product pricing data, 2009-2024)

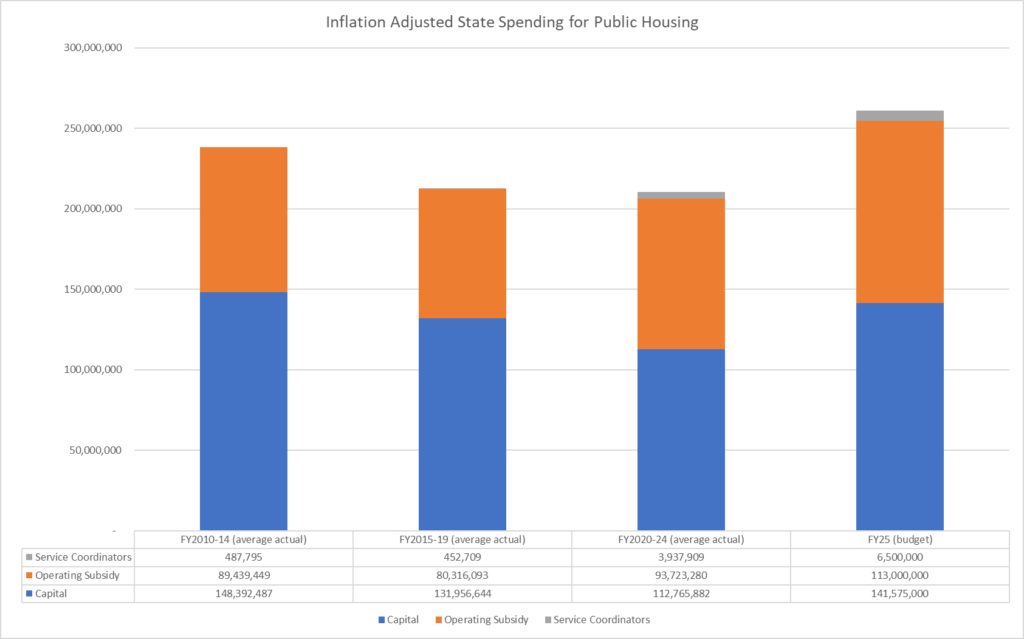

The chart below replicates the first spending chart but applies inflation adjustment. The chart shows the squeeze that housing authorities felt as prices rose through the previous decade. It also shows that the new FY25 level for the operating subsidy is a real increase, adjusted for inflation. The planned FY25 capital spending basically catches up with inflationary price increases, but when combined with continued spenddown of ARPA funds (not included in the chart) constitutes a real increase over historic levels. Continuing increases in state capital spending for housing will be needed to keep up with inflation after the ARPA funds are fully exhausted in the later part of the current capital planning period, FY25-29, but the current capital plan contemplates level spending for public housing capital from FY25 to FY29. Our bond bill does authorize higher spending, but the binding constraint will be “bond cap” — see this previous post on housing capital and this previous post on constraints on capital spending.

State Spending for Public Housing — capital and operating, FY2010 to FY2025

Spending Increases in Context

Housing authorities do charge rent to many of their tenants, but tenant rent payments are limited by law:

[a]n authority shall fix the rents for dwelling units in its projects in accordance with regulations issued by the department, so that no tenant shall be required to pay a rental of more than 32 percent of his income if heat, cooking fuel and electricity are provided by the authority, 30 percent of his income if one or more utility is provided, or 27 percent of his income if such utilities are not provided;

. . . .

[n]o elderly person of low income or handicapped person of low income shall be required to pay more than twenty-five per cent of his or her income without utilities or thirty percent with utilities for rent for dwelling units in projects or parts of projects constructed or leased or purchased under this chapter.

General Laws, Chapter 121B, Section 32 and Section 40

The same sections also include parallel language obliging the Commonwealth to make up the difference between what the tenants can afford and what it costs to operate the unit — this is the operating subsidy, referred to in the graphic above.

Any deficiency in the budget of a housing authority caused by such reduced rental shall be paid by the commonwealth to the housing authority in an amount equal to the difference between the tenant’s rent and the prorated cost of operating that unit.

General Laws, Chapter 121B, Section 32 — almost identical language in Section 40

Given the limits on rent relative to income, the actual rent roll of the housing authority will vary depending on the incomes and other characteristics of tenants. As a result, the necessary subsidy will vary greatly relative to the rent roll and relative to the maintenance component of the operating budget (which also includes utilities, administration, etc.). This wide variation in relationships among these quantities is illustrated for three housing authorities in my district in the table below.

Selected Local Housing Authority Revenue and Spending Items (Actual 2022)

| Belmont | Boston | Watertown | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shelter Rent | $1,473,738 | $9,676,892 | $2,806,656 |

| Operating Subsidy | $368,293 | $19,234,179.00 | $1,290,558 |

| All other revenue | $26,105 | $36,121,240 * | $146,753 |

| Total Revenue | $1,868,136 | $65,032,311* | $4,243,967 |

| Subsidy as % of Total of Rent + Subsidy | 20% | 67% | 31% |

| Maintenance (property maintenance alone, not including utilities etc.) | $870,807 | $7,358,808. | $1,339,446 |

| Subsidy as % of Maintenance Spending | 42% | 261% | 96% |

* Boston’s 2022 “Other – retained” revenue category includes what appears to be an unusually large one-time item. Other-retained revenue was only $6m in 2021 and total revenue was only $36m.

The legislature appropriates what it can each year to meet its operating subsidy obligations under Sections 32 and 40, but it declares those obligations met by fiat in the appropriation language for account 7004-9005. Any underfunding of the subsidy line item has the potential to disproportionately disadvantage those housing authorities with the lowest income tenants and highest subsidy needs. However, the appropriated subsidy funds are allocated across housing authorities through the process by which Housing and Livable Communities approves the budget for each housing authority. This process computes the subsidy award as the gap between the budget that is awarded and the rent roll, hopefully reducing disparities and protecting those housing authorities that are most dependent on the subsidy:

The Department approves an operating budget for the local housing authorities. Once the budget is approved, the level of spending is authorized. When income at the housing authority falls short of the approved level, EOHLC provides a subsidy for the balance. Because of the number of low-income residents in some housing authority developments, rents do not generate sufficient income to cover operating expenses and an operating subsidy is required.

HLC Informational Page on Housing Subsidies (September 1, 2024)

No simple statement can be made as to how the recent increases in operating subsidy will affect the budgets of all housing authorities, other than that they were needed and will be helpful. Similarly, it is hard to generalize about how far the increased capital maintenance funds will take us. The backlog of maintenance is deep by all accounts but varies across housing authorities. Housing and Livable Communities endeavors to allocate funds based on depth of need, but capital project spending may be constrained by the availability of local contractors to execute projects and absorb the funds. Nor can we fully anticipate how effectively 242 housing authority management teams will be able to design and bid projects to get available funds committed, even with technical assistance offered by the state.

As fragmented as the big picture is, there is strong consensus on direction: The need for increased operating support and capital maintenance spending to preserve public housing has long been broadly recognized. Over the next few years, we will want to continue to increase both operating and capital funding. We will need to continue to listen carefully to Housing and Livable Communities, to the managers of housing authorities, and to tenants and their advocates to stay in touch with the ground reality of need.

Policy Measures for Public Housing

In addition to the capital funding increases, the Governor proposed policy adjustments in the housing authority governing statutes. The final Affordable Homes Act included most of those, as detailed below. The other measures do merit continued discussion for future action.

| Policy Proposal | Action in final bond bill |

|---|---|

| Allow creation of regional housing authorities without special legislation | Not included |

| Allow housing authorities to borrow against future capital awards to fund larger projects | Included as section 30. |

| Allow regional capital assistance teams to charge larger housing authorities for services (and so expand services) | Included as section 31 |

| Streamline regional capital advisory team boards | Included as section 32 |

| Audit housing authority procedures every two years instead of every year (unless needed) | Included as sections 33, 4 |

| Exempt housing authorities from procurement laws when engaged in redevelopment projects | Not included |

| Codify tenant protections in housing authority redevelopment projects | Included as section 35 |

| Allow Alternative Housing Vouchers to be coupled to projects to support housing production | Included as section 64 |

| Raise threshold for triggering full accessibility renovations (value too low in public housing) | Included as section 120 |

| Preserve property tax exemption when public housing units are replaced by private affordable units | Not included |

Resources

- Compilations of public housing spending

- Mass NAHRO Publications

- Budget documents

- 2001 CHAPA/Harvard Study of public housing (for Cambridge and Boston Housing Authorities)

Why nothing on zoning reform? A simple fix would be to allow all existing lots in Massachusetts to be upzoned ie up to three units without requiring local zoning ordinance. I’m not opposed to more public housing but we should focus on root cause of high housing which is the burdensome local zoning process and misguided notions such as parking minimums.

Hi Keith,

I agree zoning reform is the central priority.

Here is a link to my summary on the zoning reforms passed this July.

The present post is focused on our public housing — the housing managed by our public housing authorities — but I am posting on all aspects of the issue.

Every government dollar spent on fighting other countries’ wars for them is a dollar stolen from American taxpayers. (Look up what President Eisenhower said in his farewell address.) That money is desperately needed here in Massachusetts and all across the USA, to take care of our own people. Right now our own people are not being taken care of. We need decent affordable housing. For all of us, not just the rich. It’s our obligation as loyal Americans to make sure our politicians at the federal level stop stealing our hard-earned tax dollars, and giving them away to foreign countries. If we can do that, and only if we can do that, we will be able to take care of our regional and local housing problems. Excellent preliminary plans exist to get us started…just peruse the detailed information laid out above these comments. What’s lacking to finish the job is money. We must take back the vast sums that we worked for, and which are being stolen from us by our own federal legislators. Who obviously believe that other countries’ desires are more important than our own peoples’ needs. If we fail to do that, adequate affordable housing for all Americans will never become available. It’s long past time to end unlimited welfare handouts to foreign countries, and devote ourselves to helping each other.