This page identifies principal texts defining and supporting Massachusetts plans for electrifying existing buildings and improving their energy efficiency. Many of these texts address climate policy comprehensively, but are summarized here only as they relate to decarbonizing existing buildings.

Table of Contents

- Legislation

- Official Planning Documents

- GWSA 10-Year Progress Report

- MassDEP Emissions Inventories

- Statement of Compliance with 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Limit

- 2025 and 2030 GHG Emissions Limit Letter of Determination

- GWSA Implementation Advisory Committee recommendations for 2025/2030 CECP

- Interim Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2030

- Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2025/2030

- Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2050

- Green house Gas Emission Goal for Mass Save

- Mass Save Three Year Plan (2025-2027)

- Order Establishing Commission on Clean Heat

- Major Studies

- ELM’s implementation tracker (tracks achievement of statutory deadlines)

Legislation

Green Communities Act (2008)

Established our current structure for supporting energy efficiency and electrification projects: Surcharges on gas and electric rates are used to fund utility-managed programs (rebates, etc.). The programs are conducted pursuant to three-year plans which are subject to approval by the Energy Efficiency Advisory Council and the Department of Public Utilities.

Global Warming Solutions Act (2008)

Established a commitment to measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the Commonwealth. This led through further administrative action to the definition of the goal of reducing GHG emissions 25% below 1990 levels by 2020 and 80% by 2050.

Next-Generation Roadmap for Climate Policy (2021)

Strengthened the basic 2008 GWSA commitment to reducing greenhouse gases. Requires a final 2050 goal of net-zero emissions with consistent interim goals and stronger monitoring. Specifically requires a 2030 goal of 50% below 1990 levels. Requires the setting of goals for each major sector, including “residential heating and cooling.”

Requires that in evaluating cost-effectiveness of proposed energy-efficiency measures the DPU consider the social cost of carbon.

Official Planning Documents

GWSA 10-Year Progress Report

The progress report, which was released in 2018, expresses confidence at page 10 that by 2020, the official goal of a 25% cut from 1990 levels will be achieved. As noted below, the Statement of Compliance with 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Limit finds that this goal was indeed achieved, but it will be interesting to see how much 2021 and 2022 emissions rise with the lessening of pandemic economic restrictions.

The progress report, at page 31, credits MassSave energy efficiency programs with 5.4 percentage points of the overall GHG reduction from 1990 levels.

MassDEP Emissions Inventories

MassDEP annually updates emissions inventories in several pollution categories, including GHG emissions. The most up-to-date data appears at MassDEP Emissions Inventories.

Statement of Compliance with 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Limit

Massachusetts has fully complied with the statewide GHG emissions limit of 25 percent below 1990 level by achieving emissions level at least 31.4 percent below 1990 level, based on best available data and measurements.

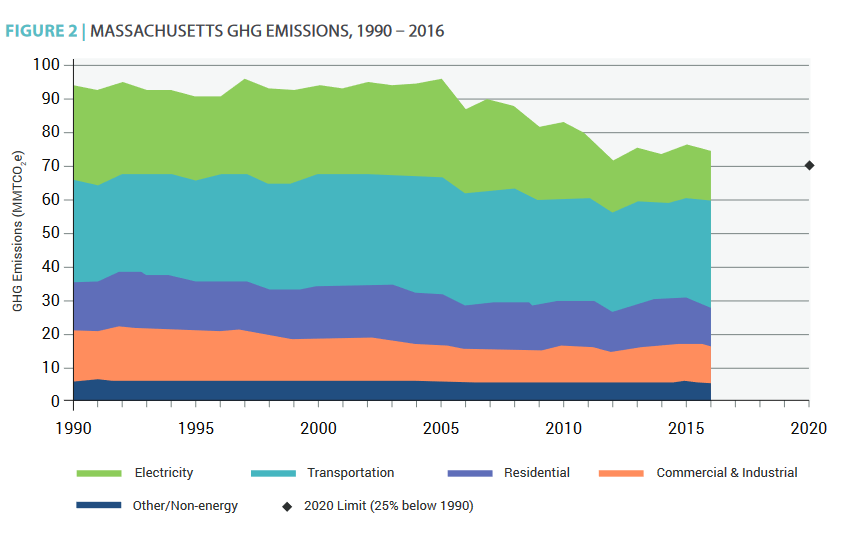

The statement compares several similar estimates and roughly finds that Massachusetts emissions have fallen from 94 Million Megatons of Carbon Dioxide equivalent (MMTCO2e) in 1990 to 64 MMTCO2e in 2020. The statement notes that the over-achievement in 2020 reflects a sharp drop in economic activity, especially in travel, due the pandemic. However, the CECP 2025/30 at page 4 states that the 2020 level would have been at least 25% below the 1990 level anyway.

2025 and 2030 GHG Emissions Limit Letter of Determination

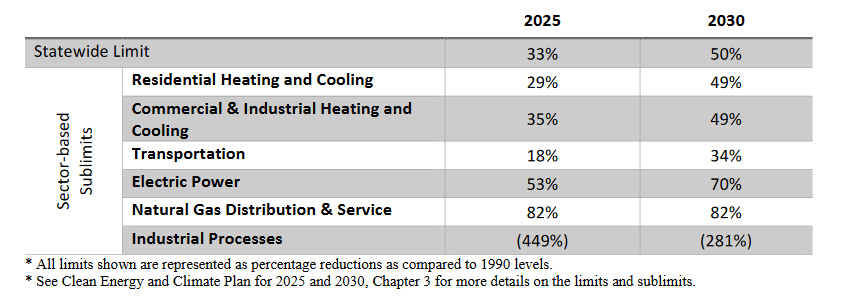

Dated June 30, 2022, this determination letter sets sector specific goals for reduction in emissions below 1990 base line emissions.

As it relates to building decarbonization, the letter makes the following finding of fact.

The analysis supporting the 2025/2030 CECP shows that . . . the lowest cost and lowest risk approach to decarbonize buildings is to immediately and aggressively pursue the use of electric heat pumps, capturing the interest of those who are interested in using heat pumps for cooling in the summers, providing financial incentives and opportunities to gain experience with using heat pumps, and help heating systems transition away from the use fossil fuels. Thus, the Commonwealth’s dominant building decarbonization strategy is electrification.

Determination letter, page 4.

Note that emissions from “Residential Heating and Cooling” basically consist of emissions from residential space and water heating. Air conditioning is electric and carbon emissions from electricity are attributed by accounting convention to the generator of the electricity, not the consumer. The leakage of refrigerants from air conditioners or heat pumps could account for a small amount of greenhouse gas emissions under the residential heating and cooling rubric.

GWSA Implementation Advisory Committee recommendations for 2025/2030 CECP

Completed in late 2020, this document, prepared by the GWSA Implementation Advisory Committee, made important recommendations for the CECP.

Interim Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2030

The interim 2030 CECP seeks a smaller overall emission reduction in 2030 (45% below 1990) than the emission reduction sought by the final 2030 CECP discussed below (50% below 1990). However, it contemplated a larger reduction in building energy emissions over the current decade (9.4 MMTCO2e) than the does the final plan (7.7 MMTCO2e from 2020 to 2030 as shown below).

The plan reviews available approaches to reduction in the building sector but does not decide how reduction should be achieved, essentially saying it is important to achieve somehow:

While other sectors in this report are presented with an emissions range, representing both uncertainty and a greater level of program optionality, driving the most aggressive pace possible in the building sector represents a key element to position the Commonwealth to achieve Net Zero by 2050 given the slow pace of building equipment turnover. The holistic sector caps identified here establish the boundaries of the emissions reductions the Commonwealth must achieve without dictating the means by which it will do so. . . . The Commission [on Clean Heat’s] work to recommend specific cap levels and the implementation approaches to reach them, will be undertaken with the understanding that the level of required emissions in the Building Sector implicates not only the ability of the Commonwealth to achieve 45% in 2030, but also its ability to achieve Net Zero in 2050.

Interim Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2030, page 33-4.

Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2025/2030

Dated June 30, 2022, the CECP reaffirms Massachusetts basic approach to emissions reductions derived from previous analysis:

Massachusetts’ approach to achieving its emissions limits and sublimits is based on three basic principles: (1) electrify non-electric energy uses, (2) decarbonize the electric grid, and (3) reduce energy costs and the costs of transition by increasing the efficiency of transportation and energy systems.

CECP 2025/30 at page 2.

The CECP makes complex economic choices as to how to allocate intended emissions reductions across sectors. These choices are reflected in the sector sublimits set in the Secretary’s determination letter released with the plan (see above). These sublimits are ultimately based on refinements of the modeling in the 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap.

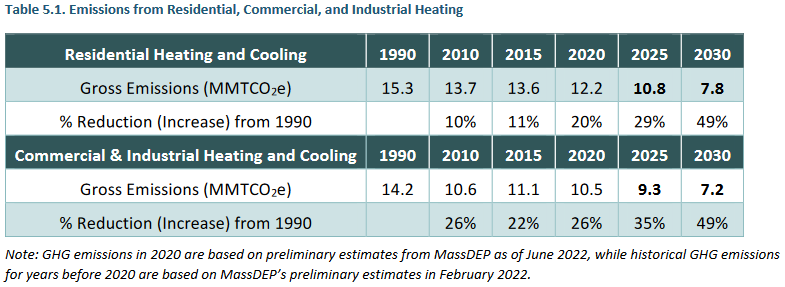

In terms of total CO2 emitted, the sub-limits translate as follows:

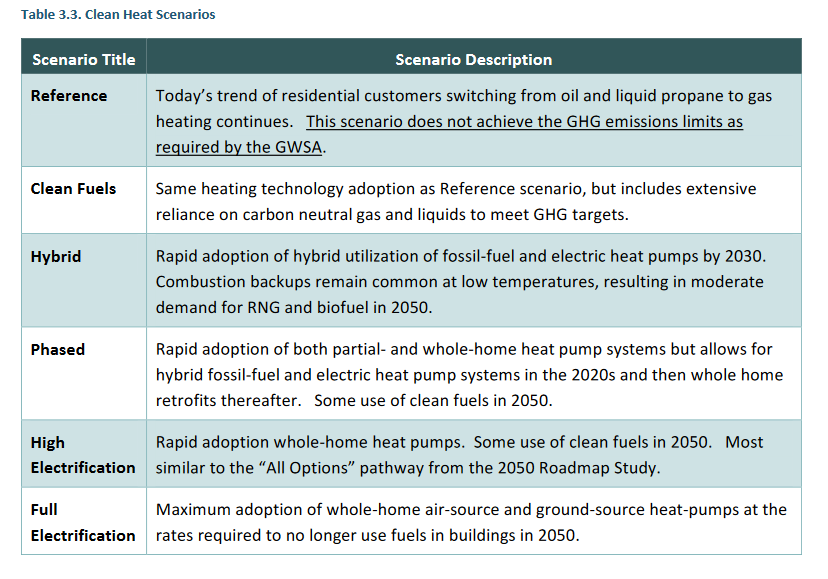

As it relates to building heat, the CECP analysis considered five scenarios.

All five scenarios include the deployment of envelope upgrades—insulation, windows, and roof—when those components are due to be replaced. Building envelope upgrades are a foundational strategy for reducing both energy system costs and GHG emissions.

CECP 2025/30 at page 27

The plan chooses to follow the “phased” scenario for electrification for the purpose of setting limits.

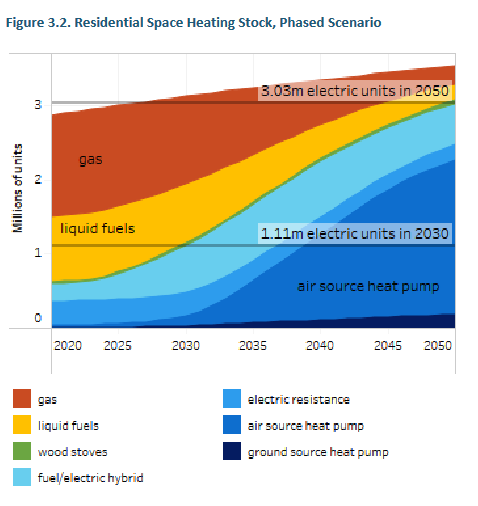

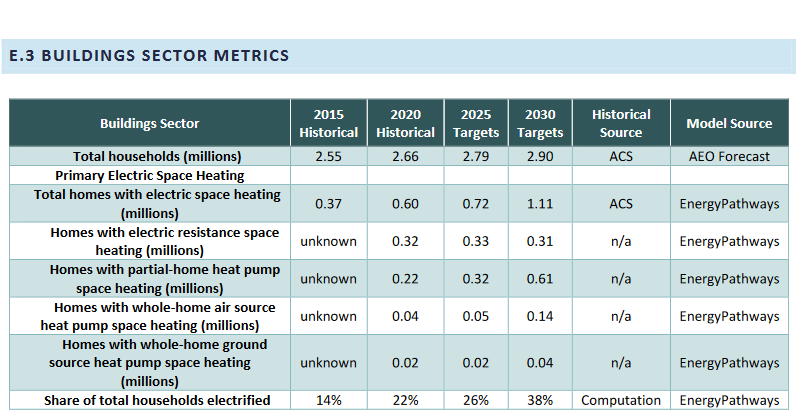

The numbers underlying this chart appear in Appendix E to the plan:

The chart above defines a goal of 790,000 homes with heat pumps installed in 2030 (.61+.14+.04 million — the last three rows before the share row total), up from 280,000 in 2020. New households assumed from 2020 to 2030 are 240,000. So, even if all new construction used electric heat pumps (sadly not likely), the plan assumes at least 270,000 full or partial heat-pump retrofits of existing homes, mostly in the latter part of the decade. The published metrics do not dis-aggregate the electrification of new versus existing households.

The plan stops short of the “high” or “full” electrification scenarios in recognition of the challenges associated with implementing heat pumps.

Despite the advantages of a decarbonization pathway that focuses on electrification, transitioning buildings to whole-home heat pumps can be costly in some circumstances, and the opportunities to replace existing heating appliances are infrequent. . . . [G]iven the current lack of experienced workforce and lack of popular knowledge about heat pumps, a phased approach focuses the near-term efforts on expanding the market for heat pumps, potentially delivering cost and performance benefits in the longer term. This allows for significant efforts needed to augment workforce training, supply-chain scale, contractor knowledge, and consumer awareness of heat pump technology, bearing in mind the urgent need to drive decarbonization efforts forward quickly. Building market capacity toward realistic near-term goals while maintaining long-term goals for widespread electrification is critical for providing good-faith guidance and coordinating gas and electric utility planning.

CECP 2025/30 at page 28

The phased scenario does allow some continued burning of fuel for heat, so it also contemplates some reduction in the carbon content of those fuels.

[T]he Phased scenario assumes a 5% reduction in the carbon intensity of pipeline gas by 2030 and a 20% reduction for fuel oils by 2030. Although the analysis favors widespread electrification over any widespread use of bioenergy and synthetic alternatives or green hydrogen for building heating, the GHG emissions rate associated with any continued use of existing fuels and gases will need to decrease significantly.

CECP 2025/30 at page 29

A perceived virtue of a strategy based on the phased scenario is that while moving heavily towards electrification, it preserves the possibility of a direction change if clean fuels start do start to become abundant and cheap. CECP 2025/30 at page 29.

As to how the Commonwealth should accelerate the adoption of heat pumps and energy efficiency measures, the CECP for 2025/30 largely defers to the ongoing work of the Commission on Clean Heat which is expected to issue its report around the end of this year. The Commission on Clean Heat is expected to recommend some system of caps on emissions that would bind energy suppliers to achieve reductions within their customer base. The Department of Environmental Protection would be charged to implement this system through regulations. CECP 2025/30 at page 52.

Whatever market mechanism is adopted, the fundamental challenge remains the same — how to encourage and support hundreds of thousands of property owners in adopting a major new technology. That will require a combination of loans, grants/rebates, consumer awareness, technical assistance, and workforce development. CECP 2025/30 at page 55.

The plan finds that MassSave may not be enough, although it is the “best-resourced and furthest reaching policy tool” that the Commonwealth has for moving property owners to clean energy. Combining the commercial and residential sectors, the plan contemplates a cut from 22.7 MMTCO2e in 2020 to 20.1 in 2025 and then to 15.0 in 2030 — a 2.6 MMTCO2e reduction in the first five years of the decade and a 5.1 MMTCO2e reduction in the second five years.

Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2050 (December 2022)

The Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2050 does not add much insight to the 2025/30 plan. It is mostly a derivative document, but there are some items that jump out:

- It gives considerable attention to work force development — a well placed focus. The document identifies a number of training efforts in motion, but does not attempt to compare their output to the likely workforce needs.

- In a table on page 23, it contemplates 1.3 million “energy efficiency envelope retrofits” as an element of achieving 2050 goals. Nowhere in the document does it refer to “envelope retrofits” again, or otherwise define the depth of retrofit contemplated. At page 60, it does point to the need for financing for building retrofits. Nor does the 2025/30 plan does not provide much clarification on the scale of the retrofit challenge. The specifics on this are buried somewhere in the models described in Appendix A of the 2025/30 plan.

- At page 17, it qualifies the goal of installing heat pumps by suggesting that some homes would have “on-site fuel backups.” That phrase appears in a graphic but not elsewhere in the document, suggesting that widespread preservation in 2050 of fossil heating systems in partial heat-pump conversions is an idea not fully processed by the team preparing the document. However, the notion is explicitly treated in the 2025/30 plans at Appendix A, page 9.

- It substantially embraces the recommendations of the commission on clean heat and foresees their rapid implementation.

- It embraces high renewable energy installation goals — “in 2050, Massachusetts will likely need approximately 27 GW of solar PV and 24 GW of wind resources.”

- It acknowledges the need to preserve some rarely used thermal electric generation capacity even in 2050: At page 73, it states: “One key finding of the 2050 Massachusetts Decarbonization Roadmap and subsequent analyses is that a power system dominated by variable renewable energy resources will need to retain certain existing dispatchable thermal generators to ensure reliability while minimizing the costs of balancing the grid. This is particularly important for meeting the peak power demand, which will increasingly shift from summer to winter due to electric heating. Some natural gas generators will continue to be necessary in 2050 to operate during times of low wind and solar availability. However, those gas generators are expected to produce a small share of annual electricity generation and, thus, GHG emissions.”

- It suggests that in 2050, to achieve zero net emissions, the Commonwealth may need to procure some carbon sequestration offsets from out of state. See page 127.

Greenhouse Gas Emission Goal for Mass Save (2022-24)

Dated July 15, 2021, this letter from the Secretary of EoEEA sets goals for the Mass Save program’s 2022-2024 three year plans.

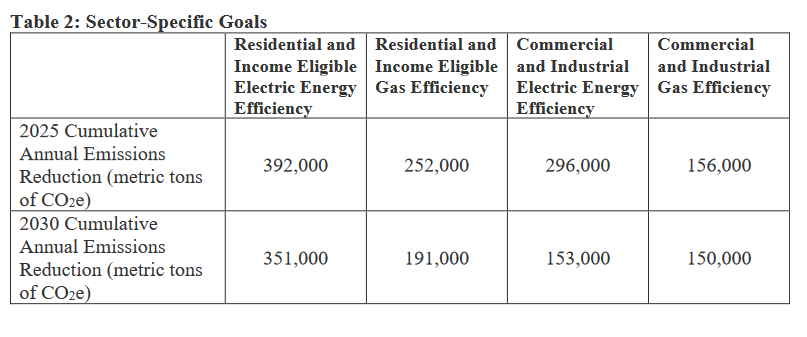

The emission reduction goals set in the chart reflect the annual emission reductions that will be in place in 2025 and 2030 as a result of the plans. Since all the plan work will be completed between 2022 and 2024, some of it will already be out of service by 2030, so the 2025 impact is greater than the 2030 impact. The top row of 2025 goals sums to 1,096,000 MTCO2e (1.1 MMTCO2e), which should not be directly compared to the reduction of 2.6 MMTCO2e by 2025 in the CECP above because the CECP “sector” goal is not net of the electricity use increase caused by electrification, while the Mass Save goal appears to reflect both the reduced direct fossil fuel use in buildings and the increased electricity use and related emissions. (An earlier version of this post did make this incorrect comparison.)

The letter further states that the plans should:

Significantly [ramp] up electrification of existing buildings through heat pump goals that set the Commonwealth on a path to achieving one million homes and 300–400 million square feet of commercial buildings using electric heat pump for space heating by 2030;

Goal Letter, Page 4 (emphasis added).

This loosely worded directive goes slightly beyond the letter of the CECP which only calls for 790,000 homes to be using heat pumps by 2030.

Greenhouse Gas Emission Goal for Mass Save (2025-27)

The March 1, 2024 goals letter for the 2025-27 three year planning process directs Mass Save to model two different emissions goals. One scenario modestly increases the target for 2030 impact from 845,000 metric tons in the 2022-4 plan to 1.0 million metric tons for 2025-7. The letter also requests a more ambitious scenario, modeling 2.2 million metric tons of emissions reductions. We should expect that the dialog will continue through the spring and summer and that perhaps a second letter will be sent confirming a chosen target. In the prior cycle, the goals letter was sent in July.

Notably the letter appears to adopt increasing realism about heat pump installation potential — cutting the 2030 goal for installation of heat pumps in half. Compare the statement below identifying a heat pump goal to the similar statement in the previous letter above.

Significantly increasing the number of residential and commercial buildings retrofitted with heat pumps and weatherized each year, with a focus on buildings served by delivered fuels, to set the Commonwealth on a path to installing efficient electric space heating in 500,000 homes and 300-400 million square feet of commercial buildings this decade;

Goals Letter Page 3, emphasis added.

Also of note in the letter is the instruction to the Plan Administrators to use a social cost of carbon based on 1.5 percent discount rate. This results in a high social cost of carbon at $415 per short ton of CO2 according to the 2024 Avoided Energy Supply Cost study. This will make more heat pump measures show up as cost-justifiable in the planning process.

Additionally, the letter instructs plan administrators to use updated EoEEA estimates of average emissions from electric power generation that are more pessimistic than those used in the previous planning period.

Comparison of instructions for computing Metric Tons of Carbon Dioxide Equivalent Emissions per Megawatt Hour (MTCO2e/MWH)

| As instructed for 2022-4 Plan | As instructed for 2025-7 Plan | |

|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 0.1869 | 0.2359 |

| 2030 | 0.1065 | 0.1277 |

Mass Save Three Year Plan (2022-2024)

Multiple documents comprise the MassSave Three Year Plan, but the Term Sheet offers a good overview. It defines a $3.94 billion program of investment on the part of utilities, mostly working through MassSave. The program is designed to achieve the required 845,000 MTCO2e of reductions in 2030. These are annual emissions reductions attributable to projects completed between 2022 and 2024 which will still be in service in 2030.

The plan includes an intensive focus on strategic electrification, supporting a total of 63,049 residential heat pump installations over the three year plan (with approximately half being installed in the third year of the plan). The CECP calls for an increase of over 100,000 residential heat pumps by 2025.

| Residential Heat Pump Installations by Type | 2022-2024 Total |

|---|---|

| New Construction | 7,615 |

| Full Displacement of fossil heat | 10,062 |

| Partial Displacement of fossil heat | 36,590 |

| Resistance electric heat to heat pump switches | 8,782 |

| Total: All heat pump installations | 63,049 |

The plan also contemplates de-emphasis of lighting measures and oil to gas switching, and increased emphasis on building energy retrofits and weatherization generally.

The full plan document highlights two major challenges that the three year plan must overcome. First, heat pump conversions do not save money for natural gas customers (the majority of home heating customers):

[C]ustomers heating with natural gas will not be a priority for electrification; however, the PAs will offer natural gas heating customers an enhanced incentive if they choose to displace their central heating with heat pumps. The reality of current commodity prices makes it nearly impossible for a heat pump to deliver operational savings, even before taking into account the substantial capital investment.

MassSave 2022-2024, full plan document at page 79 (emphasis added).

According to recent reports, while gas prices are going up this in the coming winter, it appears that electric prices are rising even faster and they are both rising faster than prices for home heating oil, so the short run economics of heat pump installation for gas customers are not getting better. As a result, the plan emphasizes installations for electric customers who heat with oil.

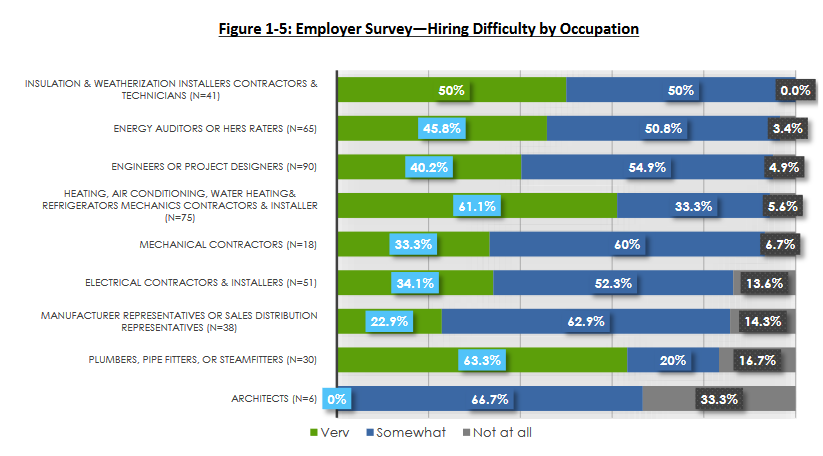

The second major challenge that the three year plan must overcome is workforce shortages. HVAC technicians and electricians are both required for heat pump installations and these are both hard to hire:

The plan recognizes these challenges and has defined its goals in recognition of them — goals, which as noted above do not fully accomplish the state’s GHG reduction goals. One can hear the back and forth between climate regulators and the utilities’ program administrators behind the following language:

Electrifying space heating will play a key role in contributing toward meeting state policy goals. The [program administrators] recognize that it is critical to increase the pace with which heat pumps, including air source, water source, and ground source (geothermal), are installed. At the same time, the program administrators believe that achieving the widespread adoption of electrification of space heating requires sustainable growth.

MassSave 2022-2024, full plan document at page 75.

The three-year plan was approved with revisions by the Department of Public Utilities. See DPU order here. See also Guidelines and guidelines order.

Mass Save Three Year Plan (2025-2027)

MassSave’s 2025-27 plan — the final version dated October 31, 2024 — proposes a $5 billion investment of rate payer funds (but see update below). The investment includes $3.4 billion that will be awarded as customer incentives (adding to the total of $6.7 billion in customer incentives awarded since 2013). The investment is a 25% spending increase above the prior 3 year plan. Of the $5 billion, $1.9 billion will be devoted to “equity” — investments in low and moderate income housing decarbonization and energy efficiency.

The plan sets a goal of 119,000 residential pump installations. This compares with approximately 75,000 in the prior three year period (including hot water heat pumps and heat pumps replacing electric resistance heat). This pace will leave the 2028-30 plan with the task of achieving approximately 300,000 residential heat pump installs to meet the 500,000 goal stated set in the Secretary’s 2024 goal letter (which was reduced from 1,000,000 installs set in the Secretary’s 2021 goal letter).

The GHG goal in the plan is 1,000,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalents, the lower of the two possible goals considered in the Secretary’s 2024 goal letter. The plan contemplates achieving this goal through (a) the previously mentioned residential heat pump installations; (b) continued residential weatherization; (c) renewed efforts to reduce emissions from commercial and industrial buildings. Electrification of C&I buildings has proven challenging and MassSave has lagged behind its C&I goals in the 2021-24 plan.

The plan include a number of new process concepts to make it easier for customers considering energy savings options to move forward to maximal decarbonization. These include single vendor “turnkey” decarbonization approaches. The plan gives special attention to engaging low and moderate income customers, including renters. The plan also commits to remedying a past pattern of delays in rebate processing.

Cross-cutting through the plan is a focus on decarbonization (prioritizing the electrification of heating through heat pumps) as opposed to mere efficiency. Quoting from the August update to the plan:

[T]he PAs designed a multi-tier incentive structure in order to better accommodate customers in different places on their heat pump journey and to encourage all customers to install a heat pump regardless of their situation. . . . [T]he PAs have also decided to continue offering incentives on a per-ton basis for partial home displacements. . . . The PAs have also decided not to impose a requirement that customers weatherize as a prerequisite to receive a partial home heat pump incentive

Quoting from the August update to the plan. p. 14-15.

Update: In its February 2025 order reviewing the plan, the DPU responded to cost concerns by ordering a cut of $500 million in the plan. This will result in some recalibration of goals.

Order Establishing Commission on Clean Heat

The Commonwealth’s principal policy tool for driving reductions in building heat emissions is the Mass Save program, but as currently constituted, it will not likely suffice to produce the planned emission reductions in the building sector. The CECP acknowledges this:

The 2022–2024 Mass Save Energy Efficiency Plans were designed to accelerate investments in building envelope retrofits, electric heating, and wind down rebates for fossil fuel heating systems. These actions contribute to the changes in building components and equipment needed to meet emissions limits and sublimits set by this 2025/2030 CECP. As determined by the Secretary of EEA on July 15, 2021, the implementation of these measures must generate cumulative emissions reductions exceeding 845,000 MTCO2e, as measured in 2030. Mass Save is currently the best-resourced and farthest-reaching policy tool that the Commonwealth can leverage to achieve GHG emissions reductions from the Buildings sector. However, the gross emissions sublimits for the Residential and Commercial & Industrial sectors sum to 20.1 MMTCO2e in 2025 and 15.0 MMTCO2e in 2030. This indicates a reduction of approximately 5.1 MMTCO2e (before accounting for reductions from electricity emissions), between 2025 and 2030, nearly all of which the 2025-2027 and 2028-2030 Mass Save plans would need to shoulder. This chapter proposes several other key programs, especially those discussed in Strategy B1, which are still under deliberation by the Commission on Clean Heat, and which could account for much of this reduction instead of the Mass Save programs. In addition, as is being considered and recommended on a preliminary basis by the Commission on Clean Heat, and discussed below, the scope and nature of Mass Save may need to be updated to fully meet the emissions sublimit for 2030. Therefore, a more specific quantitative estimate of future plans’ emissions reductions will depend on the conclusion of those deliberations and any proposed updates to the program.

Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2025/2030, page 56

Recognizing the need for additional moving forces in the building sector, the Governor issued Executive Order 596 Establishing the Commission on Clean Heat.

Policy recommendations shall include options to accelerate the deployment of energy efficiency programs and clean heating systems in new and existing buildings and transition existing distribution systems to clean energy. Policy recommendations should include financing mechanisms, incentives and other regulatory options, including a framework for a cap on greenhouse gas emissions from heating fuels. The Commission shall develop these recommendations with consideration of various benefits of the recommended policies to Massachusetts, as well as affordability, regional differences, equity, and costs.

Executive Order 596 Establishing the Commission on Clean Heat.

The Commission is to complete its work by November 30, 2022. Apparently under consideration is a new market mechanism — a Clean Heat Standard, an obligation on providers of fossil fuels to transition their customers to non-emitting fuels.

The Commission on Clean Heat has identified that Massachusetts needs a set of policy options, including the possibility of a Clean Heat Standard, that will support customers and suppliers and will ensure delivery of heating solutions at the scale needed to meet the Commonwealth’s ambitious climate, equity and economic goals.

A Clean Heat Standard for Massachusetts, p. 13

Creation of new market mechanism will focus additional pressure on the heat pump transition, but will not lower the economic and workforce hurdles for the transition.

I’ve reviewed the report of the Commission on Clean Heat here.

Major Studies

2050 Decarbonization Roadmap

The decarbonization roadmap is a collection of sophisticated models and documents that consider alternative whole-economy pathways to net zero emissions in 2050. An important conclusion of the comprehensive analysis is to focus on electric air source heat pumps as opposed to “clean fuels” for the heat of residential buildings:

Across a wide range of potential futures, electrification of end uses, particularly space

Decarbonization Roadmap, p. 45

heating through the use of electric heat pumps, was found to be the most economically

advantageous and cost-effective decarbonization strategy for widespread deployment across the Commonwealth’s building sector, especially for residences and homes, which account for about 60% of all buildings sector emissions.

The roadmap sharpens the focus on the challenge of retrofitting existing buildings:

Electrification and efficiency in existing buildings present a larger challenge, as this stock represents the bulk of emissions reductions needed by 2050. To abate these emissions, just under three million housing units will need some level of heating system retrofit over the next 30 years, including about one million statewide by 2030.

Decarbonization Roadmap, p. 52

It emphasizes the importance of deep energy retrofits for efficiency:

Ideally, almost every building would also get some degree of envelope improvement, with at least two-thirds receiving deep energy efficiency improvements. . . . Based on stock-rollover availability and cost, deep energy retrofits were cost-effectively applied to approximately 70% of all buildings in the Commonwealth in all low-cost scenarios examined as part of the Roadmap Study. As detailed in the Energy Pathways Report, the failure or inability to deploy such improvements increases the difficulty, risk, and cost of required new clean electricity generation additions, adding over $1 billion in annual energy system costs (or more than $500 per year per household) by 2050.

Decarbonization Roadmap, p. 53

Building Sector Technical Report from the Roadmap

Several technical reports accompanied the 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap, among them a report on the building sector, released in December 2020.

The report includes key facts supporting the importance of addressing existing buildings as well as new construction, finding that

81% of the expected building stock in 2050 has already been built and placed into operation. This comprises 5.9 billion square feet across the Commonwealth with the following characteristics:

* 74% of the current built square footage is composed of residential buildings;

* 65% of the current built square footage (66% of residential buildings and 62% of commercial buildings) was built before 1980;

* 81% of households and 88% of commercial floorspace uses natural gas, fuel oil, or propane onsite (with the remaining buildings predominantly using electric resistance technologies to provide heating and other thermal services).

. . .

The largest and most cost-effective decarbonization opportunity for the Commonwealth is its small residential buildings (<4 units) which are relatively easy to modify and comprise over 60% of statewide building emissions. This is particularly the case for residential buildings built before 1950 (32% of emissions while only 21% of floorspace) which have the most potential to lower occupant costs through energy efficiency upgrades.

Building Sector Technical Report from the Roadmap, p.7

As to pacing of change, the report finds:

In order to achieve required emissions reductions in and before 2050 in the Buildings Sector, significant growth in the pace and scale of heating system retrofits is required. For the residential sector, that translates to an average of nearly 100,000 homes installing heat pumps or other renewable thermal systems each year for the next 25-30 years. The commercial sector requires a comparable level of effort. Given the related increasing demand on the electricity distribution system and declining demand on the gas distribution system, this transition will need to be actively managed to ensure safety, reliability, and cost-effectiveness.

Achieving efficiency targets that help ensure reliability and cost-effectiveness will require significant growth in both number of buildings and depth of efficiency measures pursued, with nearly all homes needing some level of efficiency upgrade by 2050. This includes many, mostly older, homes receiving deep energy retrofits (e.g., more insulation, new windows) together with a new clean heating system.

Building Sector Technical Report from the Roadmap, p.7-8

DPU’s Future of Gas Docket 20-80

Given the trend to electrification, the future uses for the natural gas infrastructure are unclear. To review the extensive commentary on this issue go to DPU’s “file room” and search for “20-80.” This proceeding was still ongoing as of October 2022. An important question in that docket is whether we should expect that many buildings with heat pumps will use clean gas as a supplemental heat source in the coldest weather conditions.

Will Brownsberger, last updated January 2023.